Information. The world is just jammed with it. I’m not talking about Facebook posts and texts from your besties; I mean the sort of analog information that is constantly flowing into the holes in our head and all over our skin.

Information. The world is just jammed with it. I’m not talking about Facebook posts and texts from your besties; I mean the sort of analog information that is constantly flowing into the holes in our head and all over our skin.

But how much exactly? What would be the equivalent in terms I am familiar with — dpi, mexagpixels, gigs, etc.?

Well, the Internet has loads of answers but none are really definitive. The best I can make out is that if our eyes were digital cameras, they would each have the equivalent of around 600 megapixels and the resolution of the images we receive is about 530 pixels per inch (as a reference, the resolution of images we get on the internet is 72 dpi). Our ears are also constantly receiving sound data, and we can distinguish differences in the ~160kbps range. Our skin can feel vibration, touch, pressure, temperature and of course, pain. We have 20 square feet of skin, all studded with zillions of receptors — Our fingertips alone have 2,500 receptors per cm2.

In short, our bodies are getting a huge amount of data every second. A commonly quoted estimate says that our brains receive 400 billion bits of information each second. That’s 400 gigs, enough to fill my laptop’s hard drive, every second.

But…we have this enormous data stream coming in, and what are we doing with it? According to a recent study in the MIT Technology Review, our brains can only process 60 bits of information a second. And we are only conscious of about 2,000 bits per second. That means that .000000000015% of what comes in actually gets responded to.

Wow.

Obviously, the vast majority of the time, we are screening out almost all of what is around us. How is that even possible? Well, we are living in the preconceived patterns we built for ourselves long ago, the patterns that put most things into categories that require very little data. We simply don’t need to see every pixel of every face we encounter because we know immediately, “that’s Mary”. We may not notice that Mary is wearing a knee-length, ocean blue floral print dress with six pearl buttons, etc. because that data has no immediate value. It wouldn’t help us to survive in the wild. Those of our ancestors who couldn’t quickly form observations into categories would have been overwhelmed by data and couldn’t have responded quickly enough if Mary turned out to be a pouncing saber-toothed tiger.

Relying on these quick sorting algorithms has been a useful way to survive, what with terabytes of incoming data and the fairly slow processors in these 3-pound, neck-top computers we were all issued.

But … over time, the price we pay for this has grown higher. As the data becomes more intense (iPhones, laptops, 2000 channels, etc), we have retreated more and more into categories and preconceptions and further and further from all the stuff that’s going on around us in what we oldsters quaintly call “the Real World”. The problem is what happens when you decide that your Facebook stream is so much more manageable than the 400 gigs of real data. You will be utterly oblivious as you cross the street, lost in your smartphone, and a saber tooth tiger pounces or an SUV squashes you flat. End of your gene line.

Which brings me to drawing.

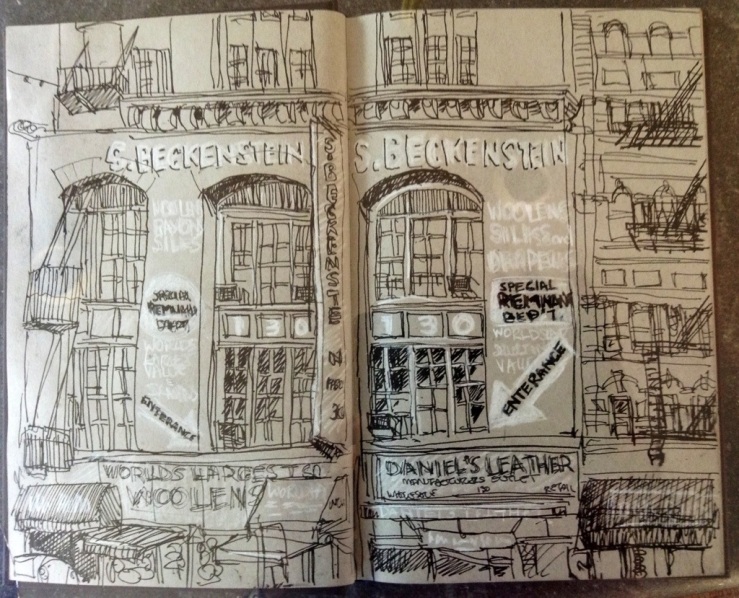

A few days ago, I was walking on the Lower East Side and I saw this building festooned with painted signs. I sat down on the pavement, leaned against a wall, and pulled out my Lamy Safari. I spent the first hour or so just drawing the building underneath the signs. I started to see that the building itself was quite interesting, that it had curved windows and lots of interesting brickwork. I discovered how the building was constructed, how the windows lineup, where the structural underpinnings were arranged. I noticed all the stores on the ground floor, their merchandise and the ways that their awnings were hung. It seemed I was tapped into the full data stream (though oblivious to my dehydration, cramped buttock, and sleeping right leg).

Finally, I pulled out a white pencil and start to letter the signs.

Here’s the thing. I had spend a couple of hours starting at this building but now I realize how much I still wasn’t seeing. Yes, I had studied its structure but I had skipped over a lot of the details, I had missed air conditioners, reflections, broken bricks and more. I had approximated so many things based on the patterns I could divine. And I had not observed the perspective or the lighting at all.

But what really blows me away was this weird mistake I made. I misspelled “Entrance”. It’s certainly a word I know how to spell. And I was looking right at the letters on the wall, paying careful attention to the letterforms, to the kerning, the condensed type, the wear of the paint, and then I misspelled “Entrance”. I can’t explain it (Oh, and to cover my goof, I purposefully misspelled it again on the left).

My brain, despite all the time and care I was taking, still had to jump to conclusions. And to a conclusion that I knew was wrong. I somehow drifted away and came back to see my hand adding that ‘E.’ Some other thing was inhabiting my skull, hands on the controls, driving along, a barely-literate lizard brain that just took over while my conscious floated away and debated what I should have for dinner. It’s literally, mind-boggling. Maybe it was a full blown right-brain thing, drawing what was in front of me and disengaged from the rational world of letters and numbers. But then why the mistake? Was I just overwhelmed by the raw data flow?

All this information. And all this human frailty. What we really need is a little wisdom.

When I travel… if I’m busy with the camera…. I don’t always remember the “essence” of a place. When I take time to draw, I am also engulfed in the sounds, smells and feel of the place… was the air cool or muggy? the light intense or filtered? and so on… My memory of that place is so much sharper than if I go back and look at dozens of photos shot in a few minutes.

LikeLike

I would posit you didn’t drift away, that you were subconsciously combining a verb and a noun directing the viewer (or yourself) into an action and a place to perform it. Anyway, that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

LikeLike

That would make an AWESOME platter!

LikeLike

Very interesting post. I think, being engaged in drawing helps brain to break labels, look at the world with fresh eye, discover, break free. You, misspelling simple word is only one more indication of your ability to see the world for real, when you draw. I love when I am able to abstract from what I know and see relationships between objects and shapes.

LikeLike

Chuckled as I read this…you almost overloaded my little “processor” with information…it can only handle about “2 bits” a second. But I love the drawing…and your conclusion. It would seem that wisdom is much harder to come by! 🙂

LikeLike

Love your insight and how you handled the overload. Still you were looking and seeing! Great job.

LikeLike

I love reading your posts. Cerebrial, provoking, and human. Please never stop, I come back and reread your posts often. There’s so much to ponder . . .

LikeLike

If an “utterance” is something we utter, why isn’t an enterance someplace we enter? Maybe you just tapped into the origin of the now-contracted version : (ent’rance)

LikeLike

Can a synapse have a hernia?

LikeLike

I love reading your posts too – this is one to ponder on for a while…… as someone who suffers from data overflow constantly I have many similar questions ….

LikeLike

Last week, we were up in Saguenay in Quebec, watching as rangers wrestled huge salmon from the bottom of a waterfall into a vat on the back of a truck. A little kid was there with his family, right in front of the salmon trap. He was looking at the screen of an ipad, and not at what was taking place directly in front of his device. He was watching the salmon on the screen. How is that for abstracting from reality? yikeys.

LikeLike

new thought – am I paying attention to my sketchbook instead of the fish?

LikeLike

It is uncanny isn’t it? I did the same thing. I spent an hour in what I thought was close observation, drawing and painting my local library, Sprucewood. It was days before I noticed that I had carefully printed Sprucebook.

LikeLike

Yes, my frequent misspellings in my sketchbooks must attest to the fact that I seem to inhabit some other zone while drawing. I always figured the part of my brain that could win a spelling bee was simply disabled when when artmaking.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Through The Artist's Eyes.

LikeLike