When I was nine in Pakistan, my grandfather’s chauffeur drove me to school every day. After a year, my grandfather told me that today he wanted me to tell the driver how to get to school. He instructed the driver to follow my directions to the letter and we would see where we ended up. Ninety minutes later, we ran into the Indian/Pakistan border. I had guided us out of the country. I shrugged and the driver turned around and took me to school.

When I was nine in Pakistan, my grandfather’s chauffeur drove me to school every day. After a year, my grandfather told me that today he wanted me to tell the driver how to get to school. He instructed the driver to follow my directions to the letter and we would see where we ended up. Ninety minutes later, we ran into the Indian/Pakistan border. I had guided us out of the country. I shrugged and the driver turned around and took me to school.

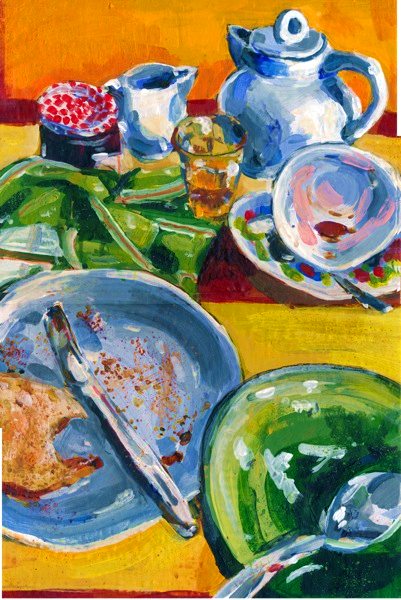

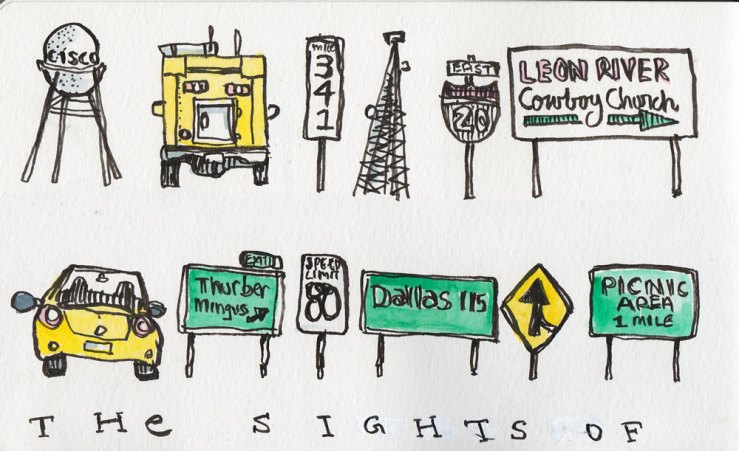

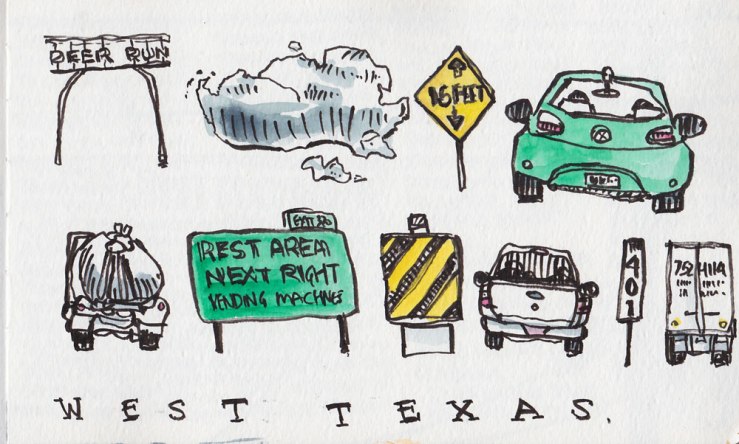

Living in Los Angeles means spending a lot of time almost lost. I am forever heading toward destinations unknown, with no landmarks to aim at, no Empire State to reckon by, no buildings more than a story or two tall, the horizon shrouded in smog or the marine layer. And Los Angeles, even more than New York, has no time for the timid, does not allow you to hesitate and peer around in confusion or slow down to read road signs or fumble for the map. It’s a brutal town that way.

Thank God for Roger L. Easton, the inventor of GPS. For nearly six months, I have relied on that computer lady to tell me exactly where to go anyhow to get there. Actually I have three computer ladies, one of whom is an Australian man. They dispense wisdom from our two phones and our car’s built-in sat nav system. When I am feeling especially disoriented and insecure, I sometimes have them all on at the same time, barking out conflicting commands in various accents or recalculating in disgust at my inability to follow the most basic orders.

All these decades later, I am just as lost behind the wheel of my truck as I was in the backseat of Gran’s Mercedes. All this step-by-step guidance is now as useless as last summer’s directions for assembling my Ikea bookshelves, in one ear and out the window. I barely know my way around town, have only the vaguest sense of where Hollywood is relative to Downtown and that there are lots of town and cities and neighborhoods in between with names that are familiar from the movies but which I couldn’t begin to drive toward if my cel service went out.

Which brings me, inevitably of course, to drawing.

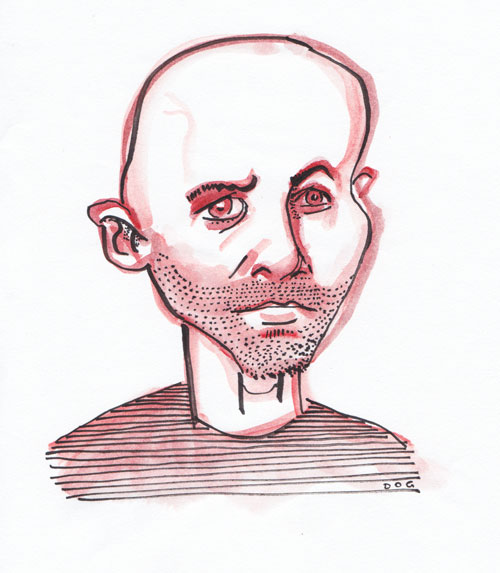

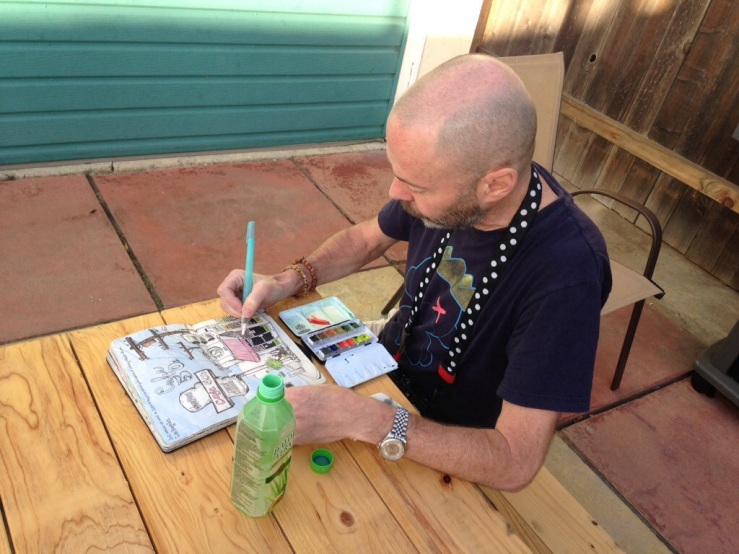

For the last few months, I have gotten more and more deeply into teaching people how to make art. I’m doing workshops, I’m writing a new book, and I’m pretending to be the co-headmaster of Sketchbook Skool. So I have to figure out how to tell other people, sometimes in just a couple of hours, how to do what I have taken a decade and a half to do.

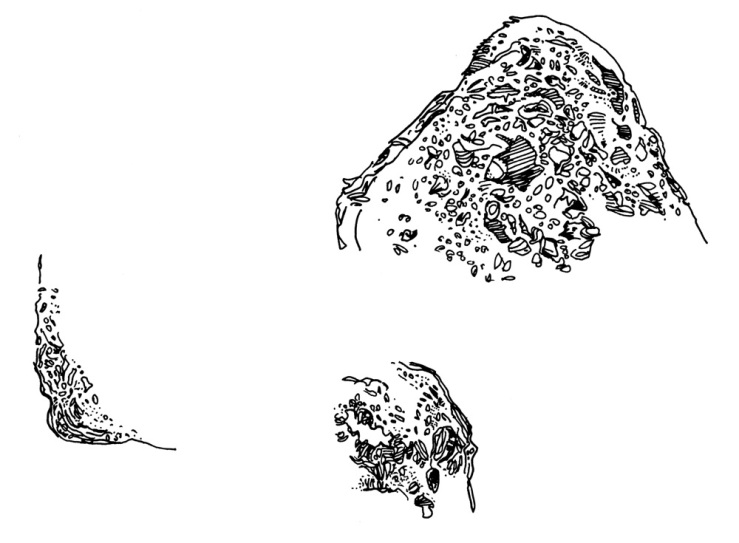

I never learned much of anything from those step-by-step diagrams in art instruction books or in “watch me paint” demos on YouTube. Following someone’s suggestion to first draw a circle and then draw two more circles and then add a triangle and then erase this bit and that till it looks like an old sea captain just has nothing to do with why I draw. I love Bob Ross’ voice and his Afro but I never learned anything about picture making from watching him paint the reflections of pine trees in a tranquil lake.

I never learned much of anything from those step-by-step diagrams in art instruction books or in “watch me paint” demos on YouTube. Following someone’s suggestion to first draw a circle and then draw two more circles and then add a triangle and then erase this bit and that till it looks like an old sea captain just has nothing to do with why I draw. I love Bob Ross’ voice and his Afro but I never learned anything about picture making from watching him paint the reflections of pine trees in a tranquil lake.

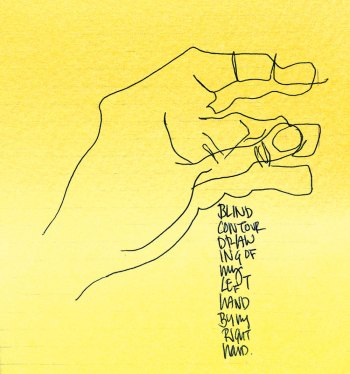

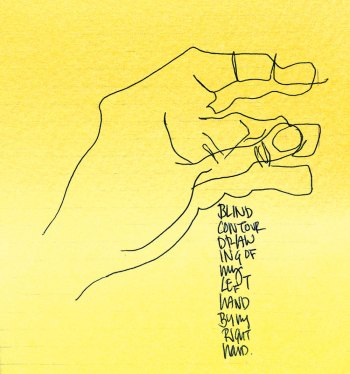

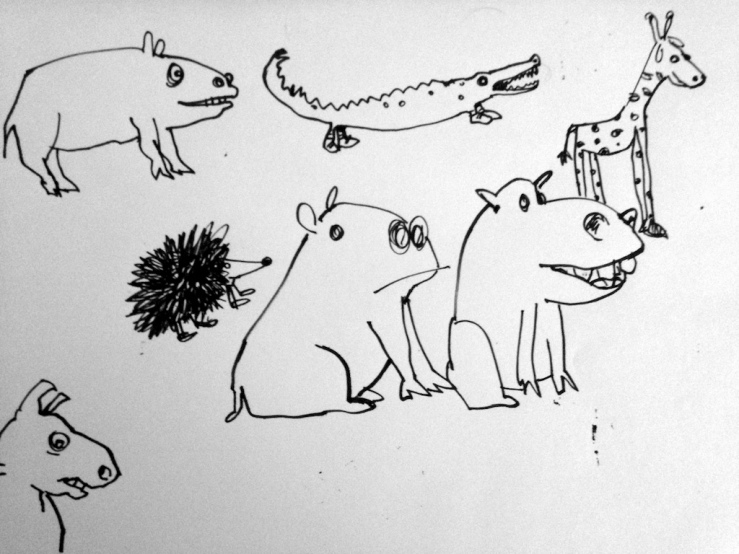

I think the way you have to teach people is by releasing a catch hidden deep inside of them. That catch that’s locking them down with the fear of making a mistake. They are so concerned that their drawings won’t look exactly like what they are trying to draw that they can’t get off their duffs and start making some marks on paper. They so badly want to be able to pick up a pencil and draw like da Vinci that anything less unrealistic seems pointless and defeating. Instead, they waste a bunch of time saying they have no talent, can’t draw a straight line, are so stupid, and so on.

But if you can just reach that catch and unlatch it, the world of possibilities swings open. Suddenly you see that drawing isn’t a way of making wall decorations or proving you have some innate gift, it’s how you see the world. And the funny thing is, there are as many ways of seeing the world as there are see-ers of the world. All cameras make the same sorts of images but all artists make things differently. As Oscar Wilde put it, ”Be yourself. Every one else is taken.”

One man wrote to us at Sketchbook Skool and said, “Before I sign up, can you guarantee that you’ll teach me to draw?” I told him, um, absolutely not. Only he can guarantee to teach himself to draw. One less customer, I guess.

So how do you teach people to make art? Well, you start by turning off the GPS lady. You can’t draw if I’m holding your hand. Instead of turn-by-turns, you start by inspiring them with some postcards of wonderful places other people have sent back from their travels and then you let them start off in a random direction.

In the driveway, you might teach them a couple of simple principles like negative space and how to take measurements but you explain that these aren’t really rules, they’re just helpful suggestions to grasp at when you worry you’re going off the rails. You hang on in the back seat and encourage them to keep going, and make a few gentle suggestions, to maybe slow down on the curves a bit, and to stop pumping the gas and the brakes together. You tell them to loosen up and not clutch the pen so tight. You point out where they made an interesting turn and you console them when they think they are hopelessly off the road. You show them that if they just keep going, they will always end up somewhere new and interesting and probably not where they thought they were headed. And the driving metaphor finally runs out when you tell them that they can and should take risks and be brave, that no one ever died making a drawing, no matter how ‘bad’ it was.

The key is to build their confidence. To let them know that they can do it. If you have confidence, then you can start to let your self come out, the self that has been watching the world through your eyeholes all these years, that has noticed odd little things. that feels deeply about certain matters, that doesn’t necessarily speak in words, and that wants really badly to share its POV with the world, if only you will let it. You can’t force that voice and vision or even describe shortcuts to it. You just have to let it feel safe and have ample opportunity to stick is head out from that deep hole in your soul.

It’s up to you. Your mom taught you to walk. But you taught you to run. Your dad taught you to drive in a parking lot. But you taught you to drive down the 405 while checking your email, singing along with Pharrell, applying lip gloss, arguing with your husband, and remembering to buy milk.

There are no shortcuts or instruction books to being a human being or to being an artist. Every single day is a lesson and the skool year never ends.

When I was nine in Pakistan, my grandfather’s chauffeur drove me to school every day. After a year, my grandfather told me that today he wanted me to tell the driver how to get to school. He instructed the driver to follow my directions to the letter and we would see where we ended up. Ninety minutes later, we ran into the Indian/Pakistan border. I had guided us out of the country. I shrugged and the driver turned around and took me to school.

When I was nine in Pakistan, my grandfather’s chauffeur drove me to school every day. After a year, my grandfather told me that today he wanted me to tell the driver how to get to school. He instructed the driver to follow my directions to the letter and we would see where we ended up. Ninety minutes later, we ran into the Indian/Pakistan border. I had guided us out of the country. I shrugged and the driver turned around and took me to school.