Artists are dismissed as dreamers. But being an artist takes focus and perseverance. It is a tough job, grounded firmly in the real.

Dreamers are roadkill. Artists work. That’s why they call it “The Work”. Not “the ideas,” “the notions”, “the dreams”, “the visions”. The Work.

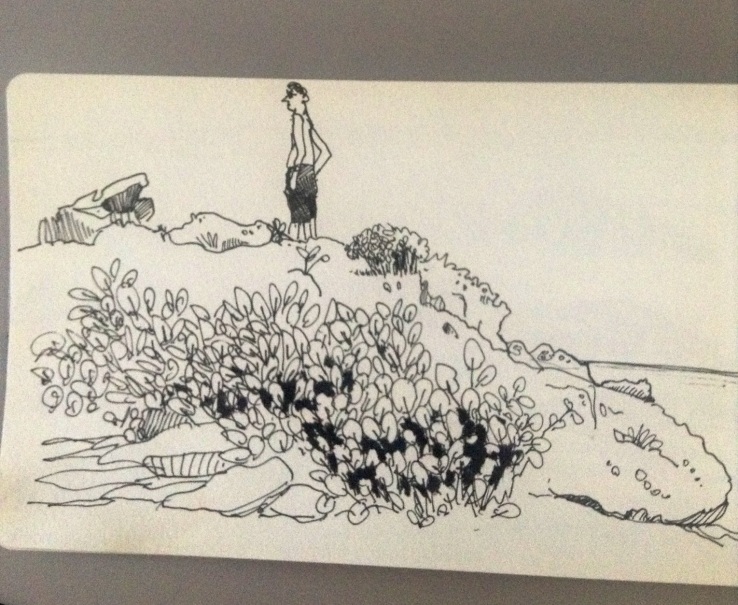

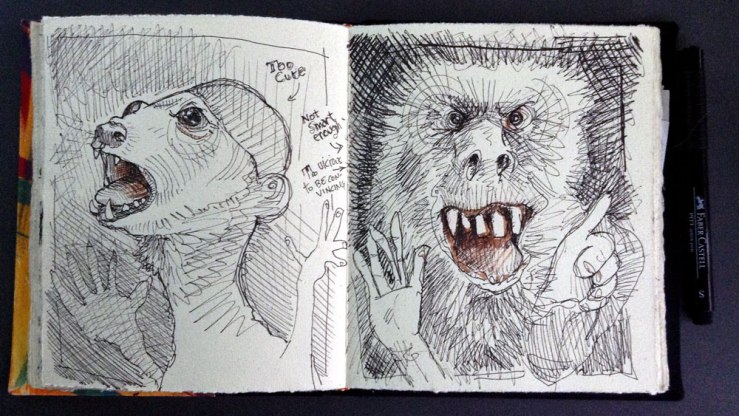

Being an artist means seeing the world as it is and having something to say about it. Most people don’t. Most people are content with hackneyed second-hand points of view. Tree hugger or tea partier, paper or plastic. But being an artist means diving into what is really out there, building your own filter from scratch, a filter that adjusts the contrast, brings out the details, heightens the textures and looks deep into the shadows. If you have nothing to say, your hands will tremble, your lines will be weak, your compositions will be flat and your audience will be yawning. You need to reach down and take a stand. On something, anything.

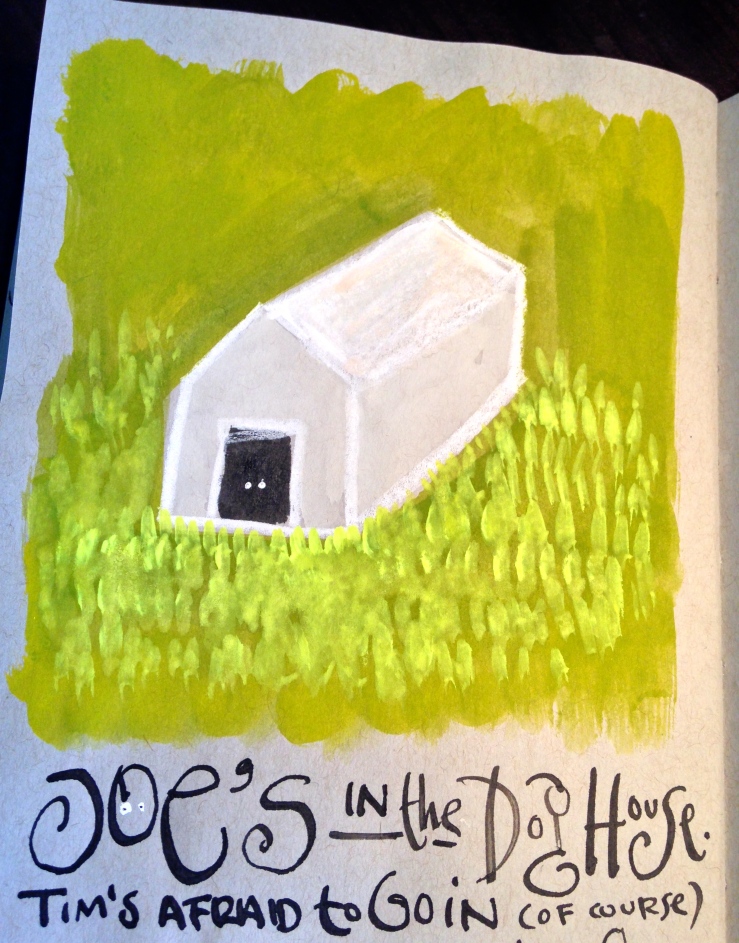

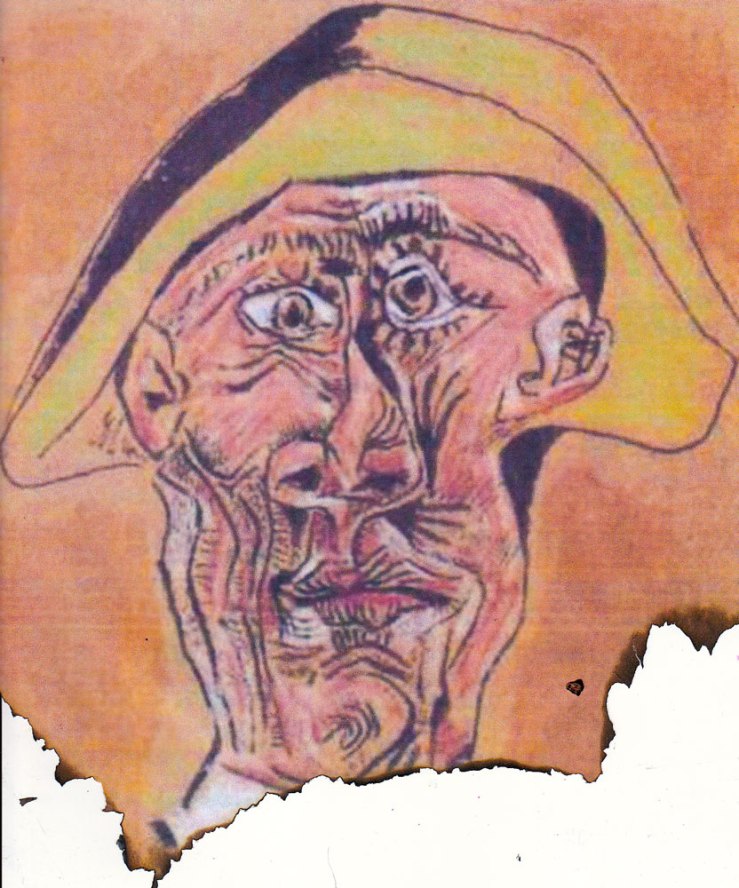

Being an artist means working to see yourself as well. To figure out what colors you see in. What shapes you like. What appeals to you. And trying in some way to understand why. Not why as in words but why as in feelings, nuances, shades. What do I like, me? I like bent things, dead things, wounded things. I like things that are beaten by the sun and wrinkled by the years. I like to see their history in their surfaces, to feel what has happened to them, to trace the map of their journey carved into their flesh, to empathize. Why do I like these things? Is it because I know I am not perfect, I have been ravaged, I persevere and I honor those who do too? Or is it because I cannot actually make beauty? I need to ask myself these questions, even though I don’t aim to ever articulate the answers. I need to see in to that ugliness and share why it is so beautiful to me. So you can see it too, so you can see the love inside your own pain.

Being an artist takes courage. It takes balls and sweat to see the world through fresh eyes and to develop the skills to express that vision and then go out on a limb and share it. Because it’s a long row to hoe, a thankless journey most of the way, a trip no one ever asked you to take and no one feels obliged to cheer you along on. If there are any spectators along the road, they are probably skeptical, probably see you as a self-indulgent weirdo too lazy to get a proper job. But don’t look to me for sympathy. Or applause. Because being an artist is a cause you choose for yourself, the rewards are in the journey, and there is no Promised Land. You have to want to proclaim your vision, to broadcast your voice, to change the world. The finish line doesn’t lie at the doors of the Whitney Biennial, it lies at the grave. Every day is a lesson and a revelation and they follow one after the other to the horizon, providing their own reward. Artists accumulate wisdom and depth and no gallery owner can take a cut of that and no auctioneer can ring a gavel down upon the lessons learned.

The only thing to goad you on is your fire and your nerve. Because after all, who asked you? Who asked you how you see the world, what’s good or bad, what needs changing, what could be. No one. You decided you had something to say and now you want to say it. No one is obligated to listen but you will make them sit up and take heed.

Being an artist means being an entrepreneur who imposes his vision, who asserts the value of what he is doing and insists people look at it and take him seriously. No one else will do it for you. No one else will come up with your business plan or a strategy or a new idea. You don’t answer to a committee or a board or market research. You make your product, you sell your product, you create your market, you get your ass out of bed each day and punch the clock you built.

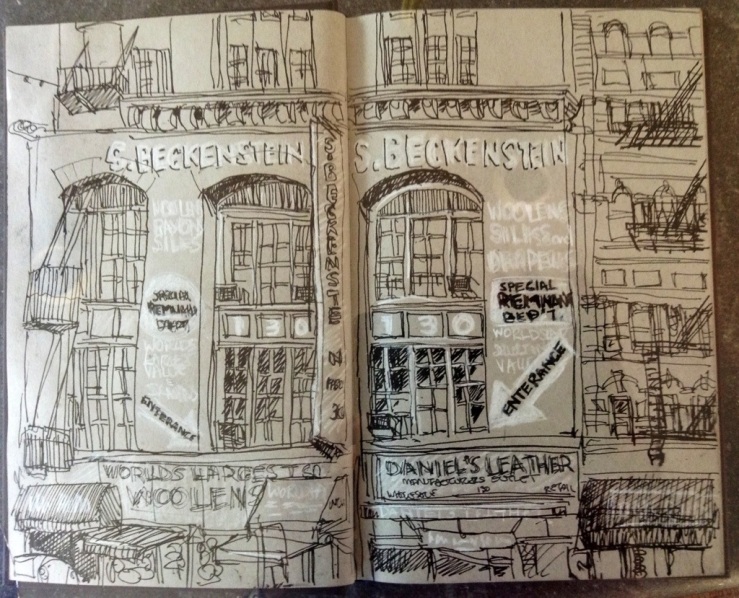

Being an artist means being a craftsman, a self-promoter, and productive without a boss, a company, a client. You are making a product no one asked to buy, sourcing your own materials, developing your strategy, and above all, shipping what you make. It can’t just sit in your brainpan or your sketchbook, it needs to be stretched, framed, and hung up for the world to see and buy and resell and love and learn from.

If that scares you, cool. Museums show about 2% of the work they own. There’s already plenty of genius in storage.

But if that excites you and inspires you, awesome. Do the work and bring it on.

“Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive and then go do that. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

—Howard Thurman