As readers of this site probably know by now, Richard Bell is an extraordinary nature illustrator who, despite the many miles and water between us, is one of my very best pals and a major influence and teacher.

When I spent several days with Richard and Barbara in their Yorkshire cottage, I go them to haul out all of his sketchbooks and made a pile that was taller than Richard at six foot something (there’s a picture of the stack in The Creative License). He has books that go back to when he was a boy; one done when he was less than ten, had an epic book plotted out that seemed to encompass the history of the entire universe. We poured over books he kept in university when he was in a department of one, the only person studying both nature and drawing. A compulsive sketcher, he has his whole life documented; we even found drawings he did at a party decades ago and we recognized that one of the guests was Barbara, a drawing done before they’d ever even spoken.

We talked about how he has made a living all these years. Barbara is a librarian and Richard has brought in his fair share entirely through drawing. His first books were published by others and he did illustrations for other writers, but ultimately he decided to take matters into his own hands and be his own press and now he has brought out many different kinds of books: a long line of field guides, tours of various parts of Yorkshire, and a lovely series of spontaneous little 32-page sketchbooks called the ‘sushi series’ for the freshness of the product. Most recently he created the enchanting Rough Patch. His work has changed in the past year or two, becoming more personal, less didactic, charting the course of his days and subjective impressions about life and nature and feeling less obliged to be all scientifically accurate. He has always seen his work, including his online journal, not as an exhibition of his art but as a way to share his scientific observations about the nature of his environment. It’s a personal diary but he still sees it as data.

Richard’s self-sufficiency is very inspiring to me; I can’t imagine any thing more perfect than wandering around observing, drawing, a painting and then printing your work and offering it to a growing public. Being so entrepreneurial is a constant evolution for Richard and he is always thinking of new and different ways to produce and market his work.

We talked about all this and more while I let the tape recorder run.

Image

RICHARD: “I’m probably one of these Victorian naturalists that kept visual diaries. I always say I’m not an artist. I’m a nature illustrator. A friend of mine always said that we illustrators are failed writers, not fine artists. Even after I went to art college, I thought I should get a degree in zoology or ecology to improve my illustrations. I got an A on my Geology A level and then I taught it for a while. It goes back to my interest in dinosaurs, a study of time; it runs through my work back to when I was seven.

It was part of my upbringing that you didn’t just do things because you wanted to, it had to have some aspect of improving one, some utility. My mum was a school teacher and she always had us doing interesting crafts and thing and she encouraged that, but my dad said you should study English and mathematics and then when you get to college you can do you art. There was never any sense of ‘go and have fun, enjoy it’. I can’t really do the whole idea of art as improvisation, free. It always ends up trying to demonstrate, explain, teach something.

There’s a tension in me between what I should drawn and what I want to draw.

I can’t walk into a landscape without thinking of it through time. I can’t just be a camera, I bring along my knowledge of the history, the formation of the land. I like faces that have responded naturally to what’s happened to them. It’s hard to draw good-looking children. You can look at a face and see the history of its people, of the effect of the landscape, of the impact of time.

I see a 200 million year old magnesium limestone from an extinct sea that once stretched from here to Poland and is now fashioned into this column on this cathedral and I think about who carved it and how he was a local craftsman who could just walk down the road and see it and then what’s happening to it because of the environment’s eroding effects and the symbolism of vines and serpents and how medieval vineyards probably grew right outside the cathedral, it’s all in there in the back of my mind, layer upon layer. But it seems too self conscious and new-age-y to write all that down so I just hope that it all gets into the drawings and then I just give it a simple caption, like: “Column, 13 century”.

Image

I’ve always thought that if one wanted to, it wouldn’t be a clever trick to go out and make a lot of money. So the question is, if I’ve been so hard up, why didn’t I take off a few months, go out and do that? Work at any old job, not art related, and just bring home the money? The closest I could do was to paint some plates.

Souvenir China plates can pay you 500 pounds. And really people are after cute dogs, so I went out to and painted some beagle in among some potted plants, one knocks them over, naughty puppies. But then I realize I can’t do cute, it’s just not in me.

I’ve never thought of getting a job outside of art, the closest I did was giving lectures at schools and talk about art, and about writing books. It was very encouraging for kids and it brought in more than a day illustrating. And yet I would go in to school to talk about being an illustrator and yet I wasn’t doing it because I was giving this same talk over and again to schools. If I’d put in the time in I talked about writing children’s books, I could have written a book. I’ve set up at street fairs and drawn portraits for money. I got quite good at catching the likenesses.

As for getting a job in a shop or an office, I’ve never really considered it. I couldn’t do waitressing, I can never remember what drinks people have ordered.

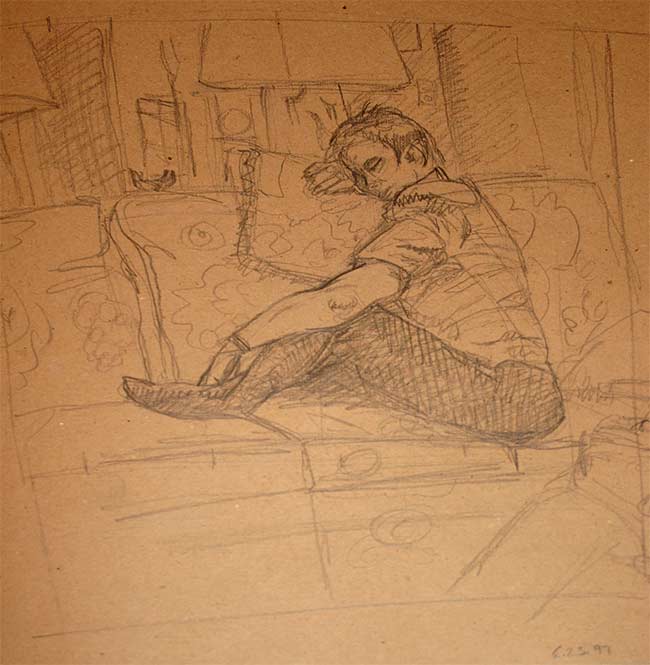

To me drawing is like sitting in comfy chair, relaxed yet supported, secure. You’re alert and yet reassured, you know what you’re doing. It is so natural, like eating or breathing, something I’ve always done. It’s hard for me to understand people who are so resistant. It’s hard for me to teach anybody who doesn’t already have that spark.

Image

When I was about 7, maybe 9, I wrote instructions on how to keep a nature diary. It was a real alternative to schoolwork, which was so rigid in those days. It was more visually exciting, more like comic strips than compositions. It wasn’t fantasy. Even when I wrote fiction, it was just storyboarding films I’d seen. I saw movies like ‘The Long Ships’ about the Vikings and then I came home and drew storyboards of the film. I kept the framing from the film and just remade it. I can’t really remember ever concocting stories, perhaps that’s a blind spot in what I do.

When I look at my early sketchbooks, it’s as if I was waiting for the Internet. Instead of them sitting in a box in the attic, that information, my observations could be useful to people. There’s such a multiplicity of ways that journals can be done and the Internet had also shown me all these different ways of doing it.

I think doing paintings and drawings to be framed is the kiss of death; too self-conscious, too cute. I’ve come to realize that life is a series of little incidents and my diary was missing the observer, so I started to add a record of my own life. I’m getting more at expressing a mood and experience these days, less about just recording the appearance of a church or a street scene.

I’m also beginning to question my obligation to be a teacher. I don’t want to step out of who I am but I am aware of the path I’m treading.”