I am afraid. I am afraid of lots of things and always have been.

When I was little, I was afraid of getting lost, of monsters, of the dark.

Later I became afraid of girls.

Of exams.

Of plane crashes.

Of my stepfather.

Of fire engines pulling up outside my house.

For a while, I was afraid of going to the ATM, afraid I had no money

I have long been afraid of my body, of the hidden diseases and disasters it is concealing.

I have been afraid of strangers who write me mean emails telling me why they no longer like me or my blog.

I have been afraid of speaking to crowded rooms.

I have been afraid of death, especially the deaths of people I love.

I have been afraid to draw, afraid I can’t do it.

If we are willing to open ourselves up and be laid bare, to respond to the moment and without hesitation, to connect deeply with our audience’s eyeballs and the minds behind, we will be freed of the bullshit that holds us back.

I have come to believe that my life’s purpose, the key to my happiness, is to pare away the things I fear.

Some I have outgrown — I can now sleep with the door closed and the lights off.

Some I have had shaken out of me — I don’t fear death much anymore. Bring it on, bitch.

Some I have just faced — I have had a physical, so I know I am healthy, regardless of what the monkey voice tries to make of that twinge in my gut, the ache in my knee. I speak to groups of all sizes, no butterflies. I drive the freeways, radio blasting. I fly hundreds of thousands of miles, cool as a clam. I quit my fucking job. I fell in love again. I moved across the country. I roar, goddamn it, and I rock.

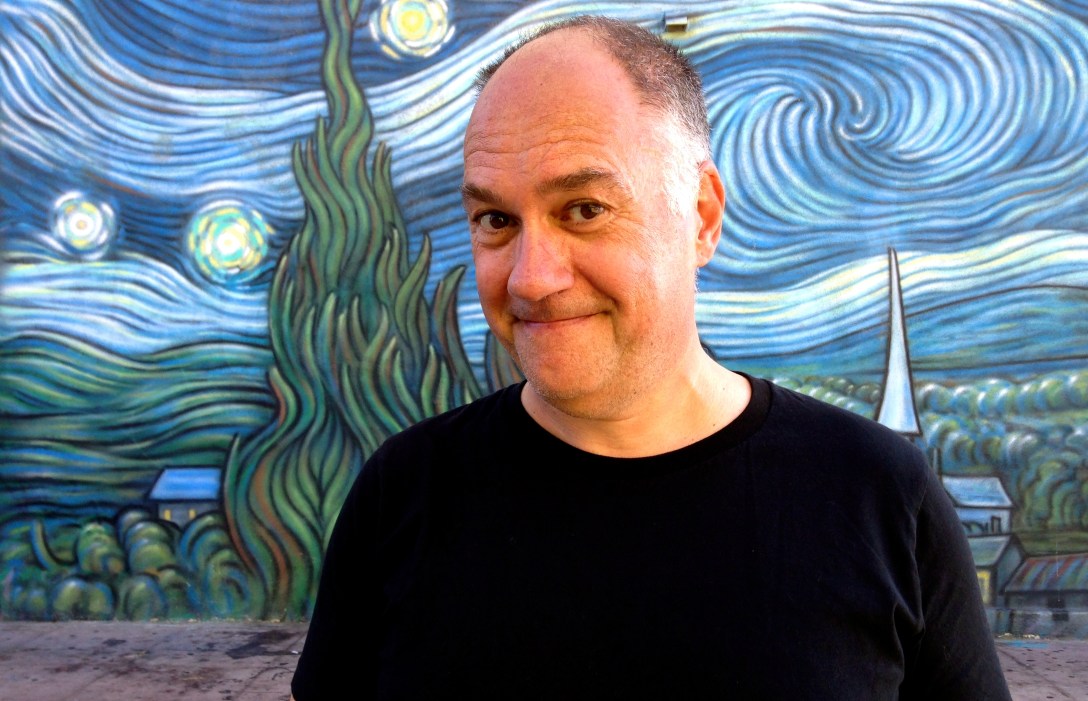

A few months ago, I overheard somebody at the gym talking about something called “Clown School”. I googled it. I found there’s one here in town. I signed up for the next intensive session. Why? Because I have no idea what it is but it sounds scary and important and utterly alien. Then I committed to not to think about it again until the day arrived. Why? So I wouldn’t chicken out.

I am now in my final day of Clown School. It was very scary — as clowns can be. Not because we wore makeup and big shoes, which we haven’t, but because we confronted many of the things that scare me the most. I stood in front of a room of strangers staring each one in the eye and telling embarrassing shameful things. I collaborated with strangers on humiliating choreography. I shrieked with fear, wailed with grief, howled with anger until I literally lost my voice. I sung a spontaneous song about what I loathe most. I danced across the stage, by myself, to demonstrate my self-confidence, and then had to do it again and again and again, until I was utterly without guile or reserve.

I have never before seen the people who saw me do this, and I sincerely hope that, though I loved them all, I never see them again. I couldn’t have done it otherwise.

Mostly, I revisited the most powerful emotions there are, familiar and often hateful emotions that I have worked so hard for so long to deny and avoid. And now, for day after day, I have sought them out and felt them surge through my body, grip my throat, shudder through my veins, cramp my stomach, churn my bowels. Terror. Loss. Humiliation. Sorrow. And joy, lots of joys — the longest lasting physical toll was the aches in my cheeks and neck and stomach: aches from too much laughter.

I am not a physical person, I spend all too much time living exclusively between my ears. But a few days of Clown School have helped me loosen my hips, have reminded me of what it is to really move with feeling, to express myself spontaneously from my gut, from my spine, from my balls, to be gripped by rhythm and to respond on a subconscious visceral level to another’s movement, to an impulse, to an emotion deep within.

Our teacher, a wise and hilarious clown, told us that clowning is about the importance of being ridiculous, because to be ridiculous is to fail, and failure is what we all have in common, the most basic and honest human experience, the one that helps us grow and change and improve and survive. If we are willing to open ourselves up and be laid bare, to respond to the moment and without hesitation, to connect deeply with our audience’s eyeballs and the minds behind, we will be freed of the bullshit that holds us back. We will tap into the deep wellsprings of creativity that lie beneath our artifice and style and self-conscious crap and hesitation and self-deception and excuses and fears. We will make art of truth.

Time and again, as I addressed old emotions in a new way, I thought about drawing.

About how the most important part of drawing is not what pen you use or the weight of your paper. At their core, drawing, painting, clowning, all art, are about letting go, of responding from your gut, of trusting, of working hard. Can you let go of all your preconceptions and finally, truly, truthfully see? Can you embrace and trust your audience rather than trying desperately to impress or con them? Can you put in the hours, the sweat, the pain of failure, so you can get deeper and deeper, looser and looser, sharper and sharper, digging down to essential truths?

Art is not entertainment. It is the way to what matters in our lives. To conquer our fears, we must face them, turn their ugly lies to beautiful truth, and share what we have made of them on the page or the stage.

I may just be a clown and a not very good one at that, but I ask you this: If you aren’t making art, what are you afraid of?