First of all, thanks for your note and, secondly sorry, for the delay in my response. Your words were quite important and I wanted to give them some time to think of proper response.

I have looked for God for many years. When I was small, I had only the foggiest sense of what God was.

He seemed like a sort of arbitrary and indifferent creature who let lots of bad things happen to people who spent a lot of time worrying about how to please him. My father is of agnostic/Protestant stock while my mother and my two stepfathers were casual Jews who were vaguely interested in the historical aspects of tradition but were at heart unblievers too, to the extent that they thought about it. My grandparents were hounded and threatened by people in Germany, Poland, Italy, India, and Pakistan, all in the name of various beliefs.

At about your age, as part of my endless quest for identity, I read a lot of Karl Marx, most of the Bible, bits of Sartre, and then eventually gave up and drank more, smoked more, met more women, and went into advertising.

When my wife was run over by a subway train, I had a renewed need for meaning. While she rehabilitated and learned to live in a wheelchair, I met with the minister at the nearby Baptist Church. I went to the local synagogue. I sat in the back of the nearest Catholic church. I went down to the Buddhist temple in Chinatown. I conferred with Hare Krishnas in the East Village. I read books and books. At the core of it all, I was looking for faith, for some confirmation of God’s presence. I didn’t want an explanation for what had happened to Patti, I just wanted to feel connected.

I found nothing that I could call my own. Nothing that was real. I tried to convince myself but I couldn’t. I don’t dispute the beliefs of those who have them but I was unable to experience what so many seem to take for granted.

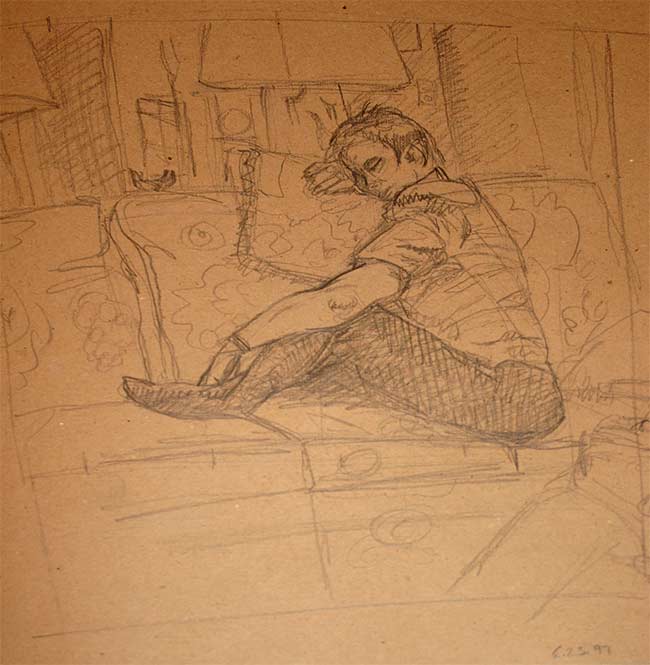

One day, I was moved to draw. I don’t know why, it just sort of happened. I drew some pictures from a magazine. I drew a vase of flowers. Then, very slowly, I drew Patti, resting on the couch. Something about that drawing was deeply moving to me. It wasn’t a ‘great’ drawing but it was mine.

I discovered that, as I drew, I felt peace. I felt connected to the things around me. I saw them deeply and somehow we became one. Was that what the Buddhists meant? Was that what Christ offered? I don’t know. I never found meaning in a church or temple. I found it in my living room.

Now I find that I want to draw. I can’t do it every day but I am drawn (as it were) to draw again and again. It doesn’t matter what I draw. It doesn’t matter whether the drawing is accurate or worth keeping and sharing. It’s nice when the drawing is ‘good’ but that’s not the point.

There were times I lapsed. Once, when my job was particularly ensnarling, I didn’t draw for three years. It wasn’t a great time and when I stopped working that way and started drawing again, I felt better.

Some of my religious friends will probably tell me that I am practicing drawing as a religion. That my drawing is a communion with God, a form of prayer. I don’t know or care. If God is that tricky and elusive, I can’t be bothered to call him by name. And I sure am not asking him for help or answers. I make my own drawings, just me and my pen.

What with my website and my books, I have found myself in this weird position of being an evangelizer for drawing. I’m not sure how it happened and I sometimes wonder if I am spending more time on the prosthelytizing than on the drawing and whether that’s a particularly good thing.

I like having people to draw with and I like sharing the things I notice about drawing when I am doing it. Drawing doesn’t harm anyone. It doesn’t pass a collection plate or condemn gay people or inspire people to blow up skyscrapers in my backyard or care one way or the other about abortion or try to effect my vote or meddle in school curricula or cast stones. But it does help me to see the beauty in people and things, to cherish what I have, to reach out to others, to favor creation over destruction, to find peace and feel more alive.

May it do the same for you.

Amen.

Your pal,

Danny