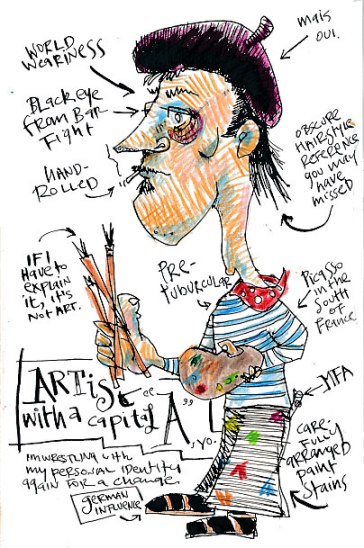

I think my mother was the first one to tell me, “You can’t call yourself an ‘artist’. Other people will decide that for you. It’s pretentious to assume the title for yourself. It’s like calling yourself a genius. Maybe you can say you’re a ‘painter’. But not an artist.”

I think my mother was the first one to tell me, “You can’t call yourself an ‘artist’. Other people will decide that for you. It’s pretentious to assume the title for yourself. It’s like calling yourself a genius. Maybe you can say you’re a ‘painter’. But not an artist.”

My mum is humbling like that.

“Teacher” is another title I am loathe to assume. I don’t have a degree in teaching, I don’t work at a school. And I think teaching is one of the most important and difficult and unrecognized jobs around. I really do think that’s a title you have to earn.

But I guess I do spend a fair amount of time telling people stuff, instructing them on how to live, to drawn, to think. So I’m either a bullying bore or I am maybe a teacher. Not that the two are the same thing, of course. It’s just that if you walked into a bank and started criticizing people’s penmanship or cracking knuckles in your local Starbucks because people have poor posture and are chewing gum, well, that wouldn’t fly. Teachers get to know better because they do.

I’ve had loads of corporate titles and they all seemed sort of ridiculous. Yesterday, a guy gave me his business card and said, “There’s no title there because I still haven’t quite figured out what it is I do.” He was being modest (he was actually the boss of a really big company) but I liked his attitude.

Let me get to the point.

One of the biggest irons I had in the fire when I left my last titled job was to put together an online class. I’ve alluded to it here a bunch of times since — but it never seemed quite right to me. Maybe it’s because of those two titles, ”artist” and “teacher” and the even more daunting combo: “art teacher.”

A couple of weeks ago, everything changed.

As result of number of amazing conversations I had in Amsterdam, most importantly with Koosje Koene, a clear, bright path has opened up. I now know what I will be doing next and I think it will be amazing.

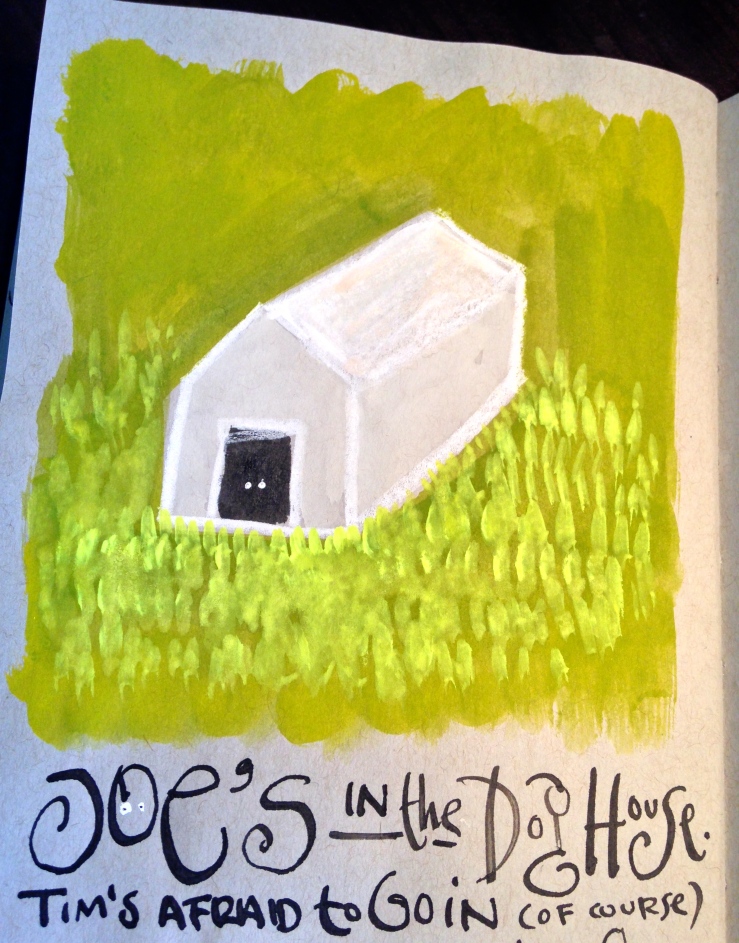

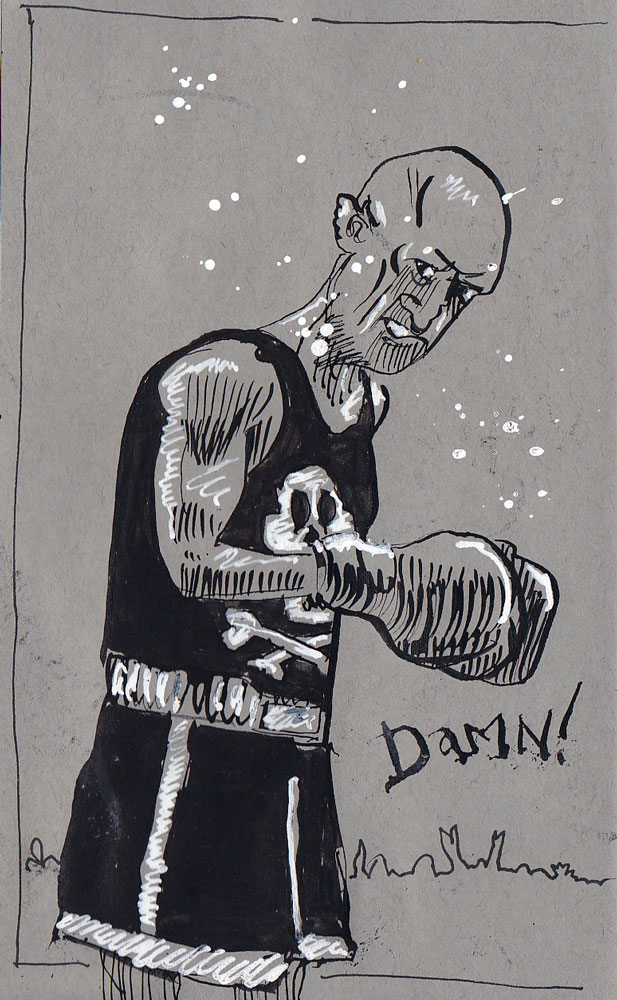

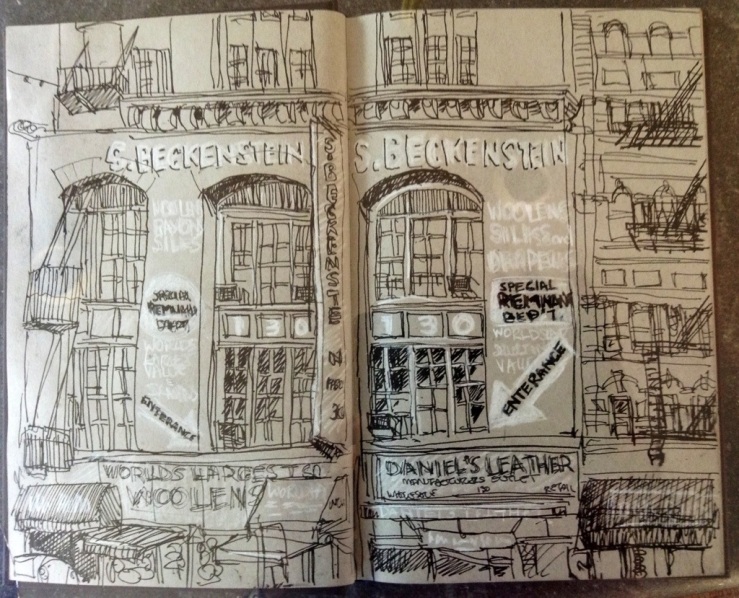

It combines everything I have been working on for the last decade. Making art; sharing with other people; meeting so many amazing “artists” and “teachers”; thinking about creativity and all of its gifts and obstacles; the Internet and the global nature of everything; Everyday Matters and what it has come to mean on Yahoo! and Facebook; the thousands of emails I have received from great people everywhere; my decades in advertising helping big companies tell their stories — all of this mass of rich stuff lumped together in one beautiful stew that finally is really bubbling.

A group of us are working on something that I really think is fresh and fantastic. It’s an answer to all those people who have asked me to do more workshops or to teach online or to give them advice or make more Sketchbook Films, all the people who are interested in art and want to make it more a part of their lives. And I think it’s a great answer, like nothing out there.

We still have a lot more work to do but we think we will be ready to roll it out in March. Gulp.

It’s a lesson that settling for an existing title or solution or direction may not always be as good as making up something brand new.

Which is what we are doing.

If you find this, whatever it is that I’m going on about, interesting, stay tuned.

And if you’d like me to update and include you in our project, send me an email. Please do. Even if you are only intrigued. Or vaguely interested. Or utterly confused. It’s gonna be big. And probably won’t involve titles. .