The first time I saw Tim was on Skype. His breeder held him up to a webcam and told us was the runt of the litter. His parents were champions. His dad was an auburn matinee idol. His mom was the rarest variety of long-haired dachshund, an English cream.

We didn’t care if he was a dwarf and a runt. We wanted him.

The breeder had named him Sly because he was. We renamed him Tim, short for Timid, which seemed kinder. Tim’s fur was black with a cream undercoat. In time, as his fur grew out he had a lavishly ruffled chest. Combined with his sleek pate and his long ears, he could look like an 18th century gentleman. One of his many nicknames was Ben, short for Ben Franklin. We also called him Mr. Nostrils because of how prominent they were.For a while we called him Black Phillip, after a goat in a movie that had been possessed by the Devil. Mainly, I called him Young Tim, even when he was no longer young.

Tim was a devil. He would slowly creep around at night, betrayed by his clicking toenails on the parquet. I’d growl, “Young Tim! Get back to bed,” and he’d slowly creep back to his basket, his plans to gulp down gallons of water and pee in the corner foiled again.

Tim was the world’s biggest hog. Whenever I went into the kitchen, he’d follow and wait expectantly for scraps to fall to the floor and he’d dart in and gulp them down. When we went for a walk, he’d glue his snout to the pavement, trying to hoover up every lump of gum, chicken bone, pizza crust or McDonalds wrapper that crossed his path. It got so I’d have to be strategic about which sides of which streets to walk him on, mapping where the trash was likely to be sparsest. When he and his brother got a little stout (the worst thing for dachshunds’ backs), we put him on rations. He got the same half cup of the same food once a day. Though we only served dinner at 5 o’clock, he would still rattle his bowl hopefully each morning, clanging it around as if to say, come on, man, give a wiener a break.

Tim was obsessive. When someone rang our doorbell, he would rub himself against the wall, licking and whining. He’d pull books off the lower shelves, sometimes removing the dust jackets to shred them into confetti. When we lived in LA, he was preoccupied with a local squirrel and would sit in the yard for hours, gazing up at the neighbor’s fence, praying for the squirrel to pop his head over so Tim could, what, we never really knew.

We also called Tim the Mailman. On every walk, he’d always deliver, peeing on the same fence post as soon as he got out the door, then pooing on the corner by the crosswalk, like clockwork, three times a day. He would never deposit anywhere else on our walks (tough occasionally, out of revenge, he’d go in the dark party of the hallway outside the bathroom).

Tim was fierce. If some dog or stranger rubbed him the wrong way he would dart and lash out, teeth bared, a growl followed by a surprisingly deep bark, like a fat man’s asthmatic cough.

But Tim was also timid. If you leaned down to pet him, he’d assume you wanted to eat him instead and he’d flop over on his back and show his round belly.

Tim had the worst breath. Earlier this year, he had his teeth cleaned and a dozen rotten teeth were plucked from his narrow jaws. For a month or two he smelt better, then the stench of rotting fish returned. Daily brushings didn’t help.

Tim was a lover. When new people came over, he’d follow them around, licking ankles, until he got picked up and carried around. That was his favorite position, not low man on the floor, but held aloft, cradled like a hairy baby, licking moisturizer off hands and foundation off cheeks, bad breath be damned.

If a guest stayed overnight, Tim would follow them into the guest room and insist on being boosted up so he could snake down under the covers and slowly co-opt more and more real estate until the humans slid to the very edges of the bed. Despite his bedhoggery, everyone insisted he sleep with them. Tim emanated love.

Tim loved to sit on the couch to watch TV but was far too short to get up on his own. He’d stand on his hind legs and tap me with his paw, then rebuffed, keep staring and staring until I picked him up. Then, up on the couch, he’d begin to rearrange stuff, nudging the remote into the floor, moving pillows, nestling into my knees or the crook of Jenny’s elbow. He was annoying as hell.

This morning, Jenny and I went through my photo archives. There were hundreds of pictures of Tim. In the snow in rubber boots, taking bath in the kitchen sink then wrapped in a towel, spreadeagled on his back in a patch of sunshine, yawning, sneezing, looking guilty. Looking at pictures made us feel better.

Soon, I’ll be ready to watch the videos. I only managed to watch one, of Tim racing like a maniac down a beach last summer, free and fleet. But videos are too much, to real. I don’t know when I’ll be able to watch the many movies I made with him, peanut butter on the roof of his mouth so he could talk about drawing. Tim was always easy to bribe, glutton that he was.

On Tuesday night, we went to the dog run. While Joe met other dogs, Tim went snuffling through the gravel. At one point I looked up from my book to see him intently digging his nose into the ground, clearly after some tasty morsel, another dog’s turd, who knows, I yelled at him and chased him off and soon thereafter we went home.

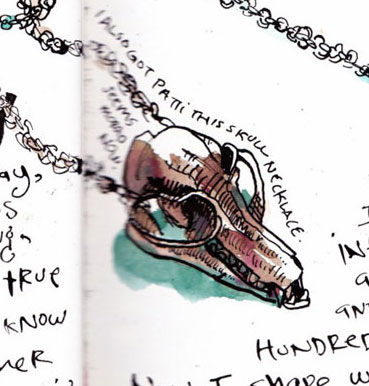

On Tuesday night, Tim began to vomit and squirt diarrhea. All night long he was up, puking and squirting and gulping down water. It’d happened before. Both he and his brother picked up stomach bug at least once a year,. It usually went away a few hours. Occasionally, it called for antibiotics and a rice diet. When Patti died, both hounds had the runs for a couple of weeks, brought on by stress-less and grief.

On Wednesday morning, Tim came out for a walk —but the mailman didn’t deliver. He threw up again, as we crossed the street and nearly got clipped by a cab. He sat under my desk and I checked him every few minutes, finally putting him up on my lap. By lunch time, I couldn’t hold off any longer. It was time to call the vet. Tim was slumping to the ground and making little noises. The vet said to come in, there was an open slot in an hour. I couldn’t wait that long and rushed over to Abingdon Square.

The vet took him in right away. Tim was dehydrated, his blood sugar low, so she gave him fluids. Then the X-ray revealed a white textured rectangular area. His small intestine was filled with something that looked like gravel. Gravel from the dog run. Gravel that was’t moving any further but was compacted in his tiny gut. Dr. Greenburgh said grimly, “He’s a very sick little dog.”

We rushed to the pet hospital on 15th street and he was whisked into the ICU. The emergency vet told us there was a possibility that if he was sufficiently hydrated that the gravel would start to pass but, otherwise, Tim would need surgery.

A couple of hours passed. Jenny had rushed over from her office and we sat numbly in the waiting room, sleep deprived and stressed out. The doctor called us back in. Tim’s blood sugar levels, his white blood cell count, other vitals all indicated that the treatment wasn’t working. His abdomen had fluid in it, probably from sepsis. It seemed his intestine had a rupture and was leaking bacteria. He need surgery immediately followed by a long recuperation period.

We went to down to the ICU to visit him. Tim lay on a table, as nurses tried to take his blood pressure.The vet had given him methadone to lessen the pain.He didn’t seem to recognize us as we stroked him and murmured into his ears. We said goodbye to him and went home to wait by the phone to hear from the surgeon.

At 8 PM, he called. Tim was ready for surgery, but he had no blood pressure. His blood sugar was still terribly low. He wasn’t responding at all and was very, very weak. The surgeon was very worried that Tim would not take it through the operation. I asked him, “Are you suggesting we don’t do it?” “It’s your decision but I am not optimistic.” I hung up and Jenny and I talked, tearfully. We didn’t want Young Tim, who has led such a love-filled and blessed life, to become some science project,doped up, sliced open, only to die among strangers in a strange place.

I called the surgeon back and we got in a cab. Twenty minutes later, we were hugging Young Tim for the last time as the doctor gave him an anesthetic and then a lethal injection.

He felt no more pain, and went to see Patti at 9 PM, hearing us murmur in his ear, “Good dog, Tim, you are such a good dog, we love you Tim, what a good dog.”