I’ve always found it exciting and a bit chilling to read about the typical day on the life of an artist I admire. They invariably go something like this:

“I spring out of bed at 5 a.m., throw some Ethiopian into the french press, and swim in the Atlantic for 45 minutes with my Rhodesian Ridgeback, Horace. Then, still wet, I sit down at my 1928 Smith Corona and write for four hours or 4,000 words, whichever comes first. I pause to eat 200 ml. of fresh sheep yogurt, steel-cut oats and Lebanese dates. Then, 100 push ups.

“Next, I allocate 43 minutes to email my editor, manager, publicist, agent, mistresses, and fans. When the tibetan sand clock that the Dalai Lama gave me gongs at noon, I walk down to an exclusive boîte on the main street of my quaint, artisanal town to eat lunch at my regular table with one or two of my equally famous artist friends.

Then I stroll home and have a two-hour nap, a massage, a high colonic, sex, two Bolivian chocolates, and return to my studio…

“Then I stroll home and have a two-hour nap, a massage, a high colonic, sex, two Bolivian chocolates, and return to my studio where I write until my housekeeper serves dinner which I eat with twenty of my closest friends and several cases of wine bottled by some aristocratic boyhood pal, then a few lashings of espresso and off to bed where I read some Keats, wash down a handful of Lunesta, adjust my satin eye shade, and dream about tomorrow’s work.”

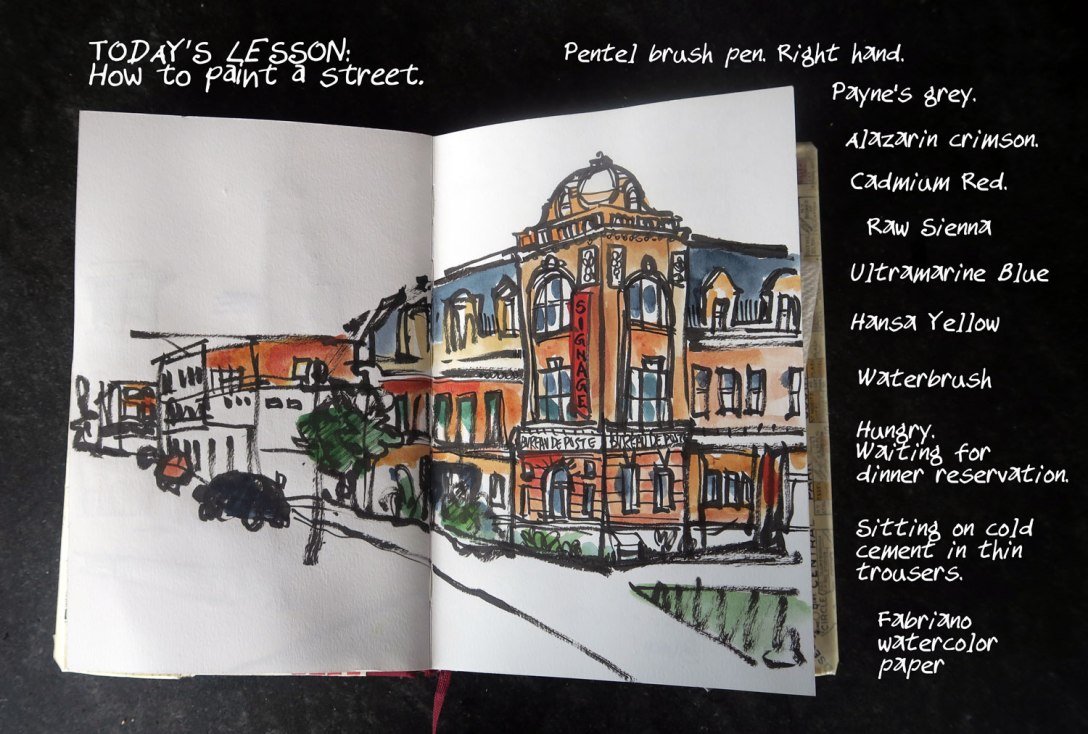

Making art takes work. For some of us, it is our work. Work without a boss, or a quota, or a time clock. And that kind of job can be very hard to keep up. That’s why artists establish routines, to get them off their duffs and into the studio. We need to be motivated by something to put down the remote or the opium pipe and saddle up.

The only one who will make us do what we do — is us. Sure, editors can give us deadlines in return for advances and gallerists can schedule gallery openings but we know deep down that we can always buy more time if we whine. No one can fire us.

For the last few months, I have pledged to myself that I would post something here three times every week, on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday at 7 am. I have written several zillion posts here over the years but this is a bit more structured. I made this pledge because a deadline of some kind would keep me more productive than just waiting for inspiration, desire, and schedule to converge. I haven’t been utterly slavish about this pledge as you may have noticed but it has kept me reasonably committed.

The key has been to establish a proper routine about it, besides this slightly guilty feeling in the back of my head that I should sit down and write something. I like to do it early, before the press of the day has begun, when the streets are quiet, Jenny and the hounds are still in bed, and I have yet to read any emails or NY Times editorials that could clutter or influence the flow. I awake with a vague notion, then make a few false starts, and soon the mechanism clicks in and the sentences spool out.

If you stay up until all hours kicking the gong and chasing chorus girls around Montparnasse, it’s a lot harder to rise with the dawn…

Starting one’s days productively takes structure. If you stay up until all hours kicking the gong and chasing chorus girls around Montparnasse, it’s a lot harder to rise with the dawn, so it’s helpful to be a little disciplined about what you do all day long, even when you aren’t creating. Eat protein, read actual books, don’t watch the Tonight Show. Repeat.

And just because my body is sleeping, my brain doesn’t get to punch out. If I mull for a minute or two about what I want to write in those minutes before sleep, it’s much more likely that I will wake up with the first sentence sticking out of my brain like the beginning of a roll of Scotch tape.

The art-making process can be mysterious but it can also be somewhat controlled. You can set a wakeup call for the muse if you give yourself a predictable program, an armature to build your work on.

I’ll write more about this next time. Which reminds me of another tip: never leave your work 100% completed at the end of the day. Park on the top of the hill, leaving half a sentence or a partially drawn face, so the You of Tomorrow can pick up the work in progress rather than wrestling with a cold start.

To wit: I will always remember what Andy Warhol said to me one evening in The Odeon, “Danny, old boy, never mix chickens, ball bearings, and…”