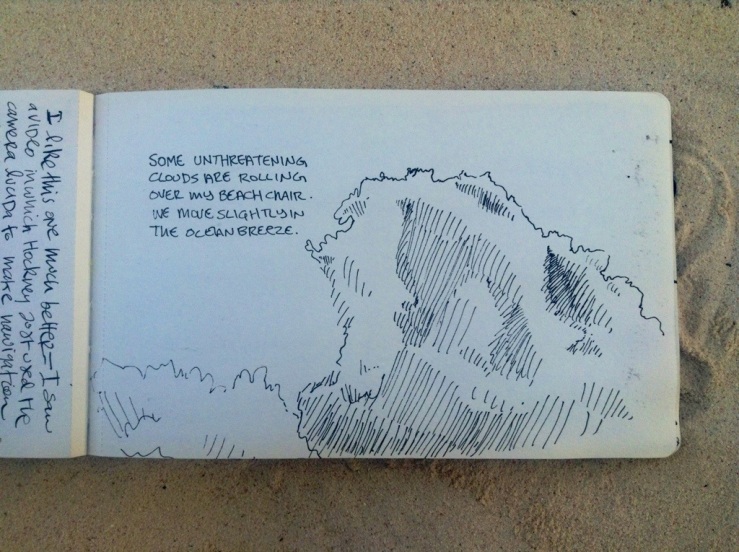

I am sitting on a powdery beach in Southern Mexico, feeling many things. The breeze in my face, the sun on my feet, a slight sense of guilty residue in my heart. My monkey bays at me, telling me that I no longer have the right to a vacation, not after this crazy plunge I’ve taken.

My body seemed to agree.

I was really sick for the last couple of days. It came upon me on Saturday at lunch time, a queazy, bloated feeling that had me bent over the porcelain by the end of the day. A sleepless night, then up at 4 a.m to catch an early flight. After a long drive down the Mayan Riviera, we reached this beach. I was green, pale, silent, and my traveling companions were more worried about me than they were willing to say at the time. But I am from hardy, working stock, and I greeted this morning with a renewed constitution and a smile.

It’s odd how often I am sick and injured on vacations. I have almost never missed a day of work and yet I invariably end up at remote chemists on tropic isles, at Italian emergency rooms, in ocean liner infirmaries. My body is a company man, and decides that the only right time to fall apart is only when it’s off the clock.

My mind is also trained to work pretty much non-stop, so vacationing can be a much -needed challenge. It takes at least two or three days for me to stop, to disconnect for emails, from the newspaper, from the meal schedules, and to let myself float away. On arrival, I spend time scheming by the pool, thinking how wonderful it is that I have this opportunity to make big plans, to re structure my office, or to make a long-term strategies. Then one day, the switch flicks and I drop it all, just vegging, listening to the pop music on the pool speaker, playing beach volleyball, having my hair braided. I think it must correlate to my sun tan lotion. As I let my SPF go down, so descends my death grip on the “reality” back home. I begin to unwind. I began to wake up and see where I am.

I am still in “on” mode this morning, my malady notwithstanding. I remind myself that despite my blazing announcement that I now have the freedom to create 24/7, I haven’t done much on my blog. Yes, it’s been a week and a half, but the monkey is impatient. And he’s not on vacation yet either. Where are all my wonderful creations? Or shouldn’t I really be busy freelancing?

Here is the lesson I draw from this internal debate:

I need to be here now. It’s wonderful that Here and Now are 78 degrees with a tropical breeze. But I need to be present always, all places. Sometimes here and now are not so nice. A crowded subway platform. A boring conference room. A hushed back room in a funeral home, smelling slightly of lavender talc and ammonia.

Regardless, I must be here now. There is nothing else. The past is just an illusion, a mental construct I drag along with me. Sometimes it seems better than now, sometimes worse, but it is irrelevant either way. The chunks I blew last Saturday are long flushed. The green pallor is gone. I can be grateful about that but that is all. I can pick at the scabs of my past decisions but regret is a waste of the present too. All that matters is now. What I am doing with this moment. With the potential that is here. To enjoy this, to be happy here, to accept what is.

And as for the future, it never arrives. All tomorrow ever is is my fantasies about what might be when it actually is. It’s not concrete or knowable and wasting now constructing plans on these prognostications is just sculpting with clouds.

On vacation, after I get over the hump, I have that realization each time. That I must enjoy this expensive day to the max, avoid getting sunburnt, have a couple pinås, eat some fresh fish, and chill the hell out. Leave the world of back home back there and back then.

And that’s really all that matters every day when I am back home too. To inhale deep, to avoid the chimp, to be in my skin, to deal with what’s happening and make it neither greater than it is with mental constructions nor lesser with denial.

Life is what is. And that’s just exactly how it should be.

That’s the lesson I learned when I first started to draw. And which I need to remind my self of all that time. That being grounded in reality, seeing what’s in front of me, warts and all, is the only way I can be happy and adjusted. That I have to keep re-realizing what art has done for me. It has shown me the beauty all around me and that it exists even in apparent ugliness and pain. If I draw it like I want it to be, it doesn’t satisfy my need for truth and connection. But if I see it as it is, here and now, I join with it, and I feel at peace.

That’s enough thinking for now. I’m off to draw those coconuts above my lounge chair. Then it’s siesta time. I dream an awful lot on vacation. Do you?

Category: Best of

The leap.

11,305 days ago, I started my career in advertising. Since then I have worked fulltime at nine agencies. In the spring of 2004, I freelanced briefly and also managed to write The Creative License. Other than those brief months, I have spent most of my hour as an adult employed by other people and working on whatever they wanted me to work on.

11,305 days ago, I started my career in advertising. Since then I have worked fulltime at nine agencies. In the spring of 2004, I freelanced briefly and also managed to write The Creative License. Other than those brief months, I have spent most of my hour as an adult employed by other people and working on whatever they wanted me to work on.

When my boy entered high school, Patti started asking me, “How much longer are you going to do this? When Jack goes to college, will you finally stop? Aren’t there things you’d rather be doing?” For most of my career, my mum has asked me, “How can you stomach working for corporate America? When are you going to give it up already?” Most of the people I work with have, at one point or another, asked me, “Don’t you make enough money from your books to stop working in advertising? It’s amazing you have done so much while holding down this job. Imagine what you could do if you did it full-time.”

I’ve done a lot of shrugging and changing of the subject over those thirty years.

A few months ago, I realized something had to change. I liked my job but I wasn’t growing any more. And it seemed like I spent a lot of time with my nose pressed to the window of my nice office, looking out at the wide world where so many people seemed to be doing so many interesting things. And now Jenny was echoing Patti, asking me if I wouldn’t be happier focussing on art, films, books, teaching, speaking…

With Jack happily at RISD and with no more real day-to-day obligations except walking my dogs, I realized I no longer had to make excuses to myself. I could finally try out something new.

I am writing in this in my empty office. The surprisingly few possessions I have accumulated over the past nine years here are in a bag and I am watching the clock for the last time. It’s my last day and in half an hour or so, I will step into the next chapter of my life.

My next steps are far from complete and I have realized what a luxury that is.

But I do have a big wish list to tackle. My editor at Chronicle is working with me on a really exciting new book project. I have the outlines for three others just waiting to be tightened up and sent off. I have written all of the first online class I will be teaching. Now, I just need to shot a bunch of cool videos to go along with it and release it to you soon. I have a big stack of art books I want to reread and study. There are so many galleries and museum shows I want to attend. Jack and I have some art projects we want to work on before he goes back to school. I have a long, long list of things I want to write about for my blog. I have several new invitations to give talks and workshops. Several very interesting new projects have just come knocking on my door that could open all sorts of new directions. And there are so many people I’ve met over the years, wonderful inspiring artists, who I want to get to know better and to find ways to collaborate with.

Most importantly, I am also keeping a large chunk of time open for serendipity. Open space that is reserved for adventure. If you have any you’d like to send my way, fire me a note.

The first big adventure: going bi-coastal. In September, we will be renting an apartment in Los Angeles and for at least a year will work there and here in New York. A fresh address, a fresh perspective, and loads of fresh possibilities. I can’t wait.

Well, I better go and say my last round of goodbyes, grab my bag, punch out for the last time, and head off into the sunset. See you on the trail!

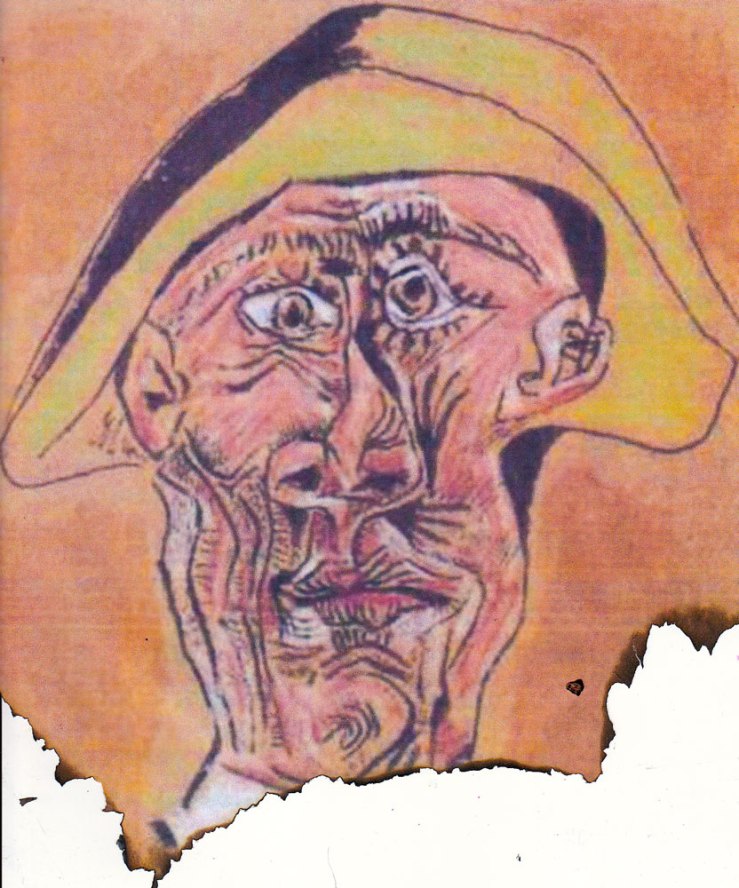

Tragedy in the Art world.

I just finished reading a horrible story in the paper. Apparently a Romanian woman’s son stole a number of works of art from a museum in Rotterdam, paintings and drawings by Matisse, Monet, Gauguin, Picasso, Lucian Freud and more. Convinced that if the paintings no longer existed, her son could not be prosecuted, the woman burned them all in the stove. Experts analyzed the ashes and concluded that her grim tale is almost certainly true. These masterpieces are lost to the world forever.

As I sat in the kitchen reading this sad story, my mind wandered off on a tangent. How many works of art have I destroyed? Not literally in my kitchen stove, but in the furnace of my mind. How many paintings have I not done? How many drawings have I aborted? How many pots have I not thrown? How many films have I not made? I thought of all the times I thought I should do some drawing and instead watched “Real Housewives”. I thought about that etching class I was thinking of taking last year and didn’t. Poof, all those would-be etchings went up in smoke. Or that three-week trip I took to Japan when I didn’t do a single sketch in my book. Or that Sketchbook Film we planned to do about a fashion illustrator but never got around to.

This isn’t the monkey talking, brutalizing me for my indolence. It’s just a fact. Every time I find a reason not to create, the art I might have made doesn’t exist. It may not have all been great art, worthy of Rotterdam, but it would have been another step on the path to better art, more fluid, more expressive, more fun.

What have you not made? And how can we fight the fire?

Fresh wisdom to trump the monkey.

I was served two giant helpings of insight this morning, both in my email inbox.

First, this note from Evelyn:

Hi Danny,

I recently ran a drawing class for adults – a sort of introduction to urban sketching, really. On the first day I shared the story of my own rediscovery of drawing, a rediscovery largely fueled by Everyday Matters. I talked about letting go of attachment to the outcome, focusing on seeing and the connection that is made with the world around us as we draw. I said don’t wait for it to be perfect before you share what you draw.

One of the participants then told me, ” I don’t have much confidence and I have no experience. The reason I signed up for this class was because the drawing on the flyer was not that good.”

It was a drawing I’d done with a bamboo pen and ink I didn’t know was water soluble, so the watercolour kind of ran into the ink and there are some pretty messy bits.

This woman’s words made a big impression on me. There is so much value in modelling joyful imperfection!!

When I teach in high schools, I don’t teach art, but the same principle holds. We need to help people to be able to love themselves unconditionally. To be self critical without anxiety and to create fearlessly.

With gratitude for all you have given, and my best wishes, Evelyn

And then, on a different but somehow related note, this blogpost from Jennifer: Live up to your full potential. It’s a lovely perspective on how to judge whether you are making the most of your gifts.

What if we redefined what this whole potential thing really meant? What if, instead of having to prove our creative selves in a particular area of art, we could reach our potential by simply living artfully? What if, instead of striving to make lots of money with our art, or show just how technically perfect we could draw… what if we engaged in our everyday lives with an artful eye, probing the moments for beauty? What if, we reached our potential by daily living the life WE HAVE, the good and the bad, the mundane and the magical, with open arms and full hearts, celebrating and capturing some of it in an artful manner along the way? What if living up to our potential as artists had MORE to do with seeing the beauty in all of life and sharing it with one or more persons, than with being able to say we have devoted our whole lives to making a career of x or y or z.

To me, these are both conversations about the monkey, about how we can cope with the incessant jabber of our self-doubt and -criticism that wastes so much energy and time. As Evelyn points out, our ‘failures’ are in fact our richest lessons. The most important things is just to start, to make, to move forward, and to shun the wimper within that woud keep us forever in the starting blocks. That voice isn’t just an impediment, it’s a cancer that chews on us, winnowing us down to smaller and smaller versions of ourselves, as we brutalize ourselves with doubt and recrimination. Be kind to yourself, and be creative.

Jennifer’s lessons comes from outside, from the larger world that uses the dollars as the only true yardstick, from the golden monkey now internalized. This monkey voice is just one of the sheepdogs of economics and really has nothing to do with us. It barks the simple cry of the market. For art to be valued financially, it must be a limited commodity. If everybody made art, it would be so common it would have no financial value. So our society is geared towards making art an exceptional behavior created by the few, a meager supply managed by the system of galleries and museums that turn human creativity into a market.

So it’s not surprising that when you graduate from crayons and want to continue creating art as part of your everyday life, you are discouraged from making at every turn. The only way that art can be sanctioned is if you pass through the system of art schools, galleries and critics that will cull the herd and protect the market.

Fortunately, the Internet has made it possible to share your creativity with other people and to get positive feedback and constructive criticism without financial transactions. The Internet has liberated us from the marketplace of art. It has restored the impulse for creative expression that has existed in our species since we painted bison on the walls of caves.

This isn’t anti-capitalist. It is pro-self-expression. And it is optimistic. Because no matter whether it is stifled by the government, by religion, by the marketplace or by snobs and bores, ultimately that impulse will return and prevail. Now more than ever.

One of the wonderful things about the Internet is that value and scarcity are no longer inextricably linked. Now good ideas are what are valuable and good ideas can be copied over and over and shared with billions and still retain their value. We live in the golden age of creativity, a new renaissance. Now making art will no longer be discouraged. it will be essential.

art with a small a is not a product. It’s a point of view. It’s a way of life.

art isn’t for museums. art is for everyday.

The Art world is about money. art is about passion, love, life, humanity — everything that is truly valuable.

The Voice.

Why are you here? Here, on my blog, why are you here?

Why are you here? Here, on my blog, why are you here?

Are you here for the reason that I’m here? Which is, I think, because I have a vague itching inside that says ‘make something.’ But the thing I feel I ought to be doing when that impulse arises, namely drawing something, is somehow not appealing right now. Maybe that’s because it’s after midnight, I’m sitting in the darkened cabin of an airplane flying to Tokyo, and the only thing I could draw at this moment is the dimly lit, freckled, meaty arm of the guy sleeping in the next seat. So I’m doing something else instead. Writing this.

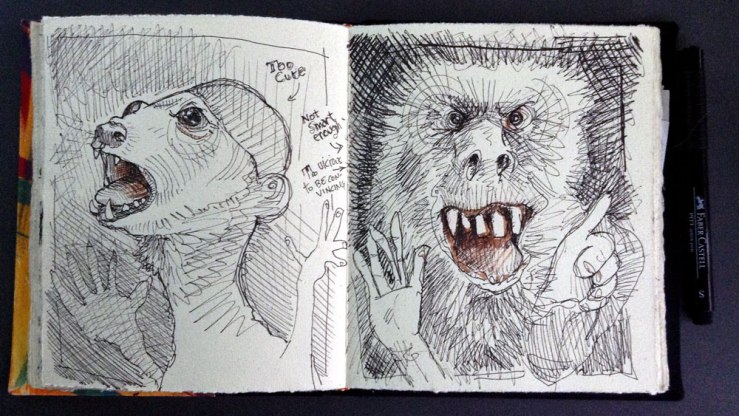

But maybe a more honest reason why I’m typing instead of drawing is that I am afraid. I’m often a wee bit afraid when I start to make a drawing — yes, even now after zillions of drawings over a decade and a half. I’m afraid of the Voice. Not the TV show (though that can be scary too) but that teeny, nagging voice saying that the drawing will possibly (or probably) suck. The Voice isn’t always there when I uncap my pen, but it often pipes up once the first line starts to go down. “Oh, well, you blew that one. It’s all gonna be repair-work from here on.” Or “Better start cross hatching now, it looks flat and weak.” Or “Come on, let’s finish this one up and watch TV.” Or just “Puhleez … you cannot draw for beans, you worthless, posturing fraud.”

Whose voice is that?

I used to suppose it was my art/shop teacher from 6th grade. Or maybe it was my second stepfather. Or my father. Or my mother. Or a kid I knew in high school who was way cooler than almost all of us. Or a guy who thumbed through one of my books in a Barnes & Noble in Dayton and shrugged it back not the shelf. Or maybe it was your voice — maybe that was the real reason you came here today, to tell me how much this drawing will suck.

But I know now it’s not any of those voices. It’s one I know much better. It’s the voice that’s editing this blogpost as I write it. It’s critiquing my typing skills. It’s correcting my posture. It’s the voice of fear.

The voice that says,”Why bother? Why take a risk? Why put yourself out there? You suck, it will suck, and nothing good will come of it.”

It’s not Linda Blair’s possessed voice in the Exorcist. It’s not the sneering, sing-song voice of the bully that cracked open my head with a rock when I was eleven. It’s a voice that sounds just exactly like mine, though it whispers, hisses even, back there in my skillet darkness of my skull.

That voice doesn’t just concern itself with drawing. No, it has opinions about most things. Whether I should wear this shirt, whether I floss enough, whether I should have desert, what my client meant by that remark, whether I should write another book, teach another class, look for a new place to live, have another cookie. It’s a busy little voice and it can think of a good reason to be afraid of most decisions, of any impending event, big or small. It can give me umpteen reasons to do something tomorrow instead of now, to ask more and more people’s opinions before I make a move, can tell me what that stranger at the cocktail party will reply if I say hi. Despite its apparent rock-solid convictions about things, the voice is always willing to switch sides with alacrity if it will serve to unsettle me. It can say I’m not good enough — or too good. It can say I should settle for the easy way out — or tell me I always refuse to go the extra mile.

I imagine that voice coming from a smallish, hunched-over ape with bright eyes and twitching fingers crouching right behind the backside of my eyeballs. Sort of like Gollum, but meatier, furred. It’s the voice that tells me the water is too cold and too deep, the girl’s too pretty, the assignment’s too hard, the competition’s too stiff, the road’s too long.

This voice has the keys to the file room and knows the combination of the vault. It can use everything I know against me, push very button, pull every lever, and it is unrelenting. It is smarter than me and it has plenty of time on its hand.

Think about this — would the voice put so much effort into fighting me if it didn’t matter? Do dragons guard empty caves? Maybe it’s so hard to do this because it matters so much?

But don’t worry about that now. It’s time to silence the voice.

Because it can be hushed. It can be beaten.

The secret is so easy, so simple, it took me ages to figure it out. I tried fighting back, debating, fresh approaches, corroborating opinions. But the answer, plain is simple, is to out-dumb it. To not look but just leap. To make not a plan but a move. To get the lead, or the ink, out. Now.

I pick up a pen and mindlessly start to draw. I don’t try to figure out what I’m drawing. I don’t consider the anatomy of the eyeball or the laws of light reflection or where the vanishing point should be. I don’t think about whether my proportions are off, or whether the subject is interesting, or whether my butt is falling asleep, or if the ink is soaking through the paper.

I am the whistling mule, head down, shoulder to the plow, just here to draw, ma’am, pushing the pen on and on. If the voice clambers out of its grotto and starts to harangue me, I switch to humming and I keep pushing that pen. And when the drawing is done, I don’t stop to look at it, I don’t evaluate it or make a few changes. I turn the page and I start the next one. I am not here to have drawn, I am here to be drawing.

And after a couple of pages, the voice has fallen silent. Given up because it is a bully and it can’t face defeat. Poor little ape. See you tomorrow.

This blogpost is a demonstration of this secret weapon. I started writing with no real idea of what I wanted to say exactly but just an urge to say something. And somehow I managed to get all these words typed and, when I get around to rereading them, I think they’ll stand up (I was about to start making some self-deprecating, parenthetic aside apologizing for how second-rate what I ended up doing is in fact, but screw it, I stand by these words and that monkey better get back in its box).

So, if you’re here because you’re killing time, time to get back to work. And if you’re looking for inspiration, you got it. Now, put on your expensive, high-performance drawing shoes and just do it.

It may well suck, but so what? A bad drawing beats no drawing every time. And good drawings are just bad drawings’ grandchildren.

What do you think? Do you ever hear the Voice? What do you say to it? Share with us.

Finding your groove

The need to make something can be a tenacious itch, clawing to be released into the world. You can try to forget it — like an early summer mosquito bite — refusing to scratch it, aiming your mind elsewhere, hoping it will just go away.

If you suppress it too often, maybe you’ll succeed in dulling your senses, in refusing to heed that inner call. You’ll have managed to wrap yourself in a cocoon, impervious, detached. Congratulations, you can focus on what’s “important,” undistracted — for now.

Sometimes, the reason you ignore that call is because you haven’t yet found the right way to scratch it. Not every medium is right for every artist. For some reason, maybe it’s physical or aesthetic, we may need to keep shopping for a while ‘till we find the right instrument. Bassoon players are somehow different from conga drummers, dancers are different from print makers. (I think it’s sort of strange that in high school band, teachers will often assign instruments to kids, rather than letting them find their perfect musical partner). You need to find your perfect groove.

A few years ago, I visited Creative Growth in Oakland, CA. It’s an amazing hive of artistic activity, all coming from people with various disabilities. I will never forget the energy in that room, with dozens of artists working all day, every day, making paintings, subjects, ceramics, mosaics, prints… it was overwhelming and beautiful. Creatively, these people seemed to have no disabilities or challenges; they’d all found their groove.

When we visited the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore recently, I re-encountered an artist who I’d met at Creative Growth years before. Judith Scott was born deaf, mute and with an IQ of 30. She was also a twin. When she was seven, she was sent away to an institution. She was separated from her sister (who was not disabled), and because of her low IQ, she wasn’t given any training of any kind. So she just sat and festered, neglected, alone.

After thirty-five years in the institution, her sister Joyce managed to spring Judith from the institution and bring her home to live with her. Soon Judith started going to Creative Growth. But at the start, she could not connect. She had no apparent interest in drawing or painting, drawing aimless scribbles and little more. She didn’t speak so no one knew what she needed to take off.

Then, one day, Judith wandered into a class given by a textile artist named Sylvia Seventy. She saw the skeins of yarn and spools of thread and suddenly found her passion. But, instead of following the projects that Sylvia was leading the rest of the class through, Judith began to make her own sort of art, something radical and new. She wrapped objects in yarns and cloth, binding them together into cocoons and nests and complex interconnecting forms. Much of her art seems to be about connection and twins, binding together networks and forms into a powerful and non-verbal emotional message. I can look at her piece for ages, following the colors and lines, and somehow feeling something so sweet and strong and comforting.

I’m not the only person who responded to Judith’s art. Her work is in the permanent collections of several museums and has been the subject of books, films and gallery shows. She made hundreds of amazing pieces in the last two decades of her life.

Judith passed away in 2005. She had lived to be 61, which is extraordinary for a person with Down’s syndrome. I like to believe that her art and her sister’s love kept her going.

I love Judith’s story because it feel so familiar to me. I can identify with what it must have felt like to go from being abandoned in an institution to suddenly seeing the light, to discovering one’s medium, one’s voice, and to see it grow richer and more complex and expressive. And how easily she might never have found her medium and remained mute and locked down. Judith didn’t have the ability to wander through an art supply store, a museum, to trawl the web, and to find her groove.

True love doesn’t just appear. You have to keep your eyes open and look for it. Just because you don’t yet know how to scratch it, don’t ignore that itch.

More than you could possibly want to know about me.

Last week, the lovely and inspiring Jane LaFazio sent me a bunch of questions for an interview and I decided to turn them into a little film, shot in my home and the places I frequent about town. It’s a little long, 20 minutes or so, but vaguely amusing:

You can see Jane’s comments about it here;

http://janeville.blogspot.com/2012/07/interviews-as-inspiration-danny-gregory.html

You suck. But enough about you.

Creative people care so very much what others think of them. They ask, “Is it any good?” and then wait not just for what you say but for how you say it. It’s not enough to be effusive in your praise. Were you sincere? Really? And does the fact that you say you like it mean your opinion isn’t worth listening to? Are you Paula Abdul? Or Simon Cowell? Is there a ‘But…” lurking in your praise? If you give constructive advice. is it personal? Are you saying I, as well as my work, suck?

(Sure, there are the rare, apparent exceptions who don’t give a good god-damn what anyone else says, but I suspect that they too are motivated by the perceptions of others — they just hide it better.)

Sometimes, others’ verdicts are integral to what you’re making.

In my business, the success of an idea is entirely decided by what someone else decides it’s worth. Does the client think it’s good? Does the consumer think it’s good? Does my boss like it? Do my peers? Award show judges? Et cetera.

If I was showing my work in a gallery, the dealers’, critics’ and patrons’ opinions would make or break me. If I act in a show, a review could take bread off my table. Some person I’ve never met at the New York Times could devastate my next book.

When I draw in public, a passerby might possibly be sneering, even if just to himself, at my presumption at being ‘an artist’ while scrawling in my sketchbook. If I yank the page out of my book, I must be careful to tear it up so no one piece sit back together and scoffs. I shred the pieces small so no one thinks that I myself don’t know how much it sucks: Sure , I can’t draw, but at least I have the taste and judgment to know it. Or, maybe I’ll leave it in my book but write a long essay next to it about how bad it is, like a reminder and a slap in the head not to do such crap again. If anyone sees it, well, they’ll read my notation and know I know better.

Do you go through this? So did I, until I discovered a little fact, that boils down to this: by and large, no one cares about anyone else but themselves. I don’t mean that we’re all hateful and selfish, just that we’re almost always wrapped up in our own issues and can’t much be bothered with anyone elses’s actions, except as to how they pertain to us.

Doubt me? Prove it to yourself. Start a conversation with anyone and see how long it takes them to steer the conversation back to themselves:

“I love your shirt.

“Thanks. It’s new.

“Really? I can never wear pink.

“I didn’t think I could either…

“But you look great in it. Where’d you get it? Loehman’s?

“No, I …

“I love Loehman’s. When I can find stuff that fits me.

“Huh.

“Yeah, I must have gained ten pounds since Christmas…

Try listening instead of talking and see how long the other person will talk about themselves. Be prepared to wait because virtually anyone, if given the stage, will hold on to it eternally.

“What are you doing?”

“Drawing”

“I can’t draw a straight line. Even as a kid, I never could. You’re great. You must have taken a lot of lesssons.

“No, not really.

“Well, I just have no talent. I used to play the guitar but you know, who has the time. I’m so busy at work since I got that promotion…

Sound familiar? A couple of years ago, I gave a colleague, a ‘creative’ person, a copy of Everyday Matters. A month later, he hadn’t said anything about it so I asked him what he’d thought of it. He said,

“Yeah, it was great. You have that stuff in there about Wales and my father’s from Wales so I thought it was interesting.”

“Wales, really?”

Yeah.”

I waited for more but that was it.Wales. Sigh.

I’m not talking about hard-core self-involved people, mega-bores. I mean everyone, including me (goes without saying, I hope) spends most of their time thinking about themselves or how what others are doing affects them.

Put simply: no one is nearly as interested in what you do as you are. No one is judging it as hard as you, or analysing it, or wondering about it. The only time they really get involved is when your success or failure could effect them. Will looking at your work entertain or divert them for a moment (oh, your drawing sucks, never mind then) If you draw and they don’t are they less than you? WiIl your work make theirs look worse? Will it make them money? Can they use your technique to improve their work? WiIl praising you oblige you to them?

Seriously, what other motives do they have? And are those sufficient reasons for your to be concerned? Are these sorts of opinions what drive your work? Are you making art so others can make money or feel better about their own abilities (or worse)?

Think about it: we all, even Brad Pitt or George Bush, occupy a tiny percentage of any other given person’s interest, That’s why some of us are interested in achieving fame: because it takes all those tiny percentages and multiplies them across millions of people. Eventually that adds up to something.

And because we are all, at best, living in our own self-reflecting bubbles, you should relax and do what you want. Stop caring so much about externals. Make what you like in the way that you do. Sure, maybe you’ll manage to be a blip on someone else’s radar, but that’s not why you bother. Live and make art for the only person that matters or truly cares.

[Originally published on: Apr 21, 2006 @ 19:17]

How to draw

To learn just about any task, we start by breaking it into its smallest component parts. That’s how a computer works, breaking every operation into millions of unambiguous instructions which are then executed sequentially at the speed of light. Cooking a complex French dish becomes possible, even easy, if you have a clear recipe which breaks the preparation down into a long series of clear parts. Even playing a Beethoven symphony is technically a matter of reading the notes from overture to finale.

To learn just about any task, we start by breaking it into its smallest component parts. That’s how a computer works, breaking every operation into millions of unambiguous instructions which are then executed sequentially at the speed of light. Cooking a complex French dish becomes possible, even easy, if you have a clear recipe which breaks the preparation down into a long series of clear parts. Even playing a Beethoven symphony is technically a matter of reading the notes from overture to finale.

Drawing works the same way.

Most anything you’d want to draw is made up of straight lines and curves. You can almost certainly draw a short, reasonably straight line. And with a little care you can probably draw an arc or a fairly round circle. Improving your ability to do either of these things is primarily a function of how slowly you you do them. And practice will make you better.

But you’re probably no more interested in drawing lines and arcs than you are in learning to boil water or to play a single note on the piano. It’s assembling the individual components that makes the idea of drawing satisfying and challenging. But that’s all it is, a challenge, not an impossibility, no matter who you are.

Drawing is about observation, about dismantling whatever you are looking at into the lines and curves that make it up. So let’s start with somethings simple, say a pencil or a coffee mug. Examine it for a minute or two. Let your eye follow the outer edges of the object and really think about what you are seeing. Ask yourself questions. How long is a particular stretch of edge? What happens when it encounters another edge? What sort of angle do lines make when they meet? Are the lines on one side parallel to those on the other? Keep scrutinizing and studying, like a detective grilling the subject so you can get at the truth. The truth is right in front of you and yet it is elusive. Why? You are not used to seeing clearly because you are bogged down with preconceptions. You want to overcome those preconceptions about what a pencil looks like by forgetting that it is a pencil. Instead you want to see it just as as line and curves and angles.

If you are having trouble, stop looking at the object from two perspectives at once, with your right eye and your left. Close one eye and now you will be committed to a single perspective. Just as your pen does on paper, you will now be dealing only with a 2-D world. Drawing that pencil is just a matter or recording your observations on paper, copying the length of one line, then adding on the curve, noting down an angle. Try it. Run your eye down the edge, then run your pen down the paper. Slowly, slowly. Then connect the next edge, checking your angle. The slower you go, the more you’ll know. Work your way around the whole object, checking parallel lines, seeing where things meet up. It’s just like measuring a window for drapes or flour for cookies. Slowly, slowly. Measure twice, cut once, as the carpenters say.

If you screwed up somewhere, just correct yourself. Don’t erase or freak out, just redraw the lines, training your brain, your eye, your hand.

Take a break, pat yourself on the back.

Soon, do it again. And again. Then when you’re ready, add another object and draw them together, thinking about the relationship between the two. Lay your pencil near your mug. Look at the shapes that are defined by their edges. Think about the negative space they form (that’s the chunk of table that lies between them). Get into the habit of looking for negative space. Look at a tree’s branches. The sky you see between the branches is negative space. So is the carpet or wall you see between chair legs. Observe it. Draw it.

Devote half an hour a day to this sort of observation and recording and, within a week, you will begin to amaze yourself.

The next step is just to add more complexity. Find more complicated objects or scenes to draw. Set up a still life of common objects. get intricate. Draw the seeds on top of a bagel or the hairs on your dog’s face. Sure there are a lot of them but tackle them one by one. Draw a detail then move over to the next one and record it. Keep going and then step back and see the forest after drawing the trees (A word of caution: challenge yourself but don’t raise the bar so high that you start to feel like a failure).

Once you are rolling, make drawing an everyday thing. Record the world around you. Draw your breakfast, your cat, your spouse’s shoes, your child’s toys. Join our Yahoo! group and try out some of Karen Winter’s challenges.

Your inner critic may well balk at all this. First off, how could it be that easy? Well, it is. Now that you know the elements (careful observation, recording lines, angles and curves) and are willing to practice them for a little while, you will soon be able to draw anything on earth. Sure, it will take more time to make and record accurate observations quickly but it’s not beyond reach. I’m not a bird describing to you how to fly; you have all the necessary equipment and abilities already. You simply need to focus, slow down, and persevere. The biggest step is shedding the preconception that you can’t do it.

Second objection: is it art? I have no idea. At first, it will be hard to put a lot of style or expression in your drawing but, trust me, every line you draw, right from the get go, is pureyou. Soon you will have enough control to lead your work in any direction you choose. Think of this as a golf lesson. I am teaching you to hit the ball. It’s up to you to keep working and lower your score. You probably won’t wind up being Tiger Woods … but so what? You’ll still have loads of fun.

Want to know more? Read a good book.

A religion

oah: HI!

Tess: Hey Danny!

Noah and I are reading your book Creative Lisence in class and it has been one of the most inspiring book we have evr read, and we are on the 20th page! It is like a religion all it’s own. It has all the elements and honestly has done more for me than any religion has even begun to.

Are you religious? This is the only of your books iv’e read so I don’t know if you had alluded to it, but Noah was just wondering. He wants to know if you would want to start a religion with him. o.O

If you have the time, please write as back as we wuld love to be in contact with such an inspirational person ^_^

Thank You,

Tess and Noah

——

Dear Tess and Noah:

Indeed it is a religion.

Here are the ten commandments:

I. Thou shall not be afraid of making things.

II. Thou shall not erase. Well, not too often.

III. Thou ought to keep a journal of your life and draw the stuff that strikes you as cool and make little notes next to it and stuff.

IV. Thou shall not not play around.

V. Thou shall not covet they neighbor’s art work as thine own.

VI. Thou shall remind other people that they can draw even if they think they can’t.

VII. Thou shall not judge too harshly.

VIII. I 8 a dead horse.

IX. Thou shall draw on the Sabbath, but not only on the Sabbath.

X. Thou shall not make lists with more than IX things in them.

Your pal,

Danny