A couple of days ago, I had a mindful moment in an unlikely place. I had to go to a government office to renew a document. It was a large room filled with rows of chairs facing a series of steel desks with computers and clerks. Not Kafkaesque, just dead boring. I wasn’t perfectly prepared for this chore — it was one of a series of appointments I had that day and I had rushed there from a completely unrelated matter.

As a result, all I had with me was a sheaf of important documents. In my hurry, I hadn’t brought anything to while away the time, no book, no sketchbook. But the Kindle app on my phone was stocked with several books if need be. I figured I’d be fine.

After much paper shuffling and stapling, the desk clerk handed me a number and pointed at the sign on the wall: “No phones, cameras or recording devices.” If I took out my phone, she said, I’d be booted and have to make a new appointment for another time.

I shuffled over to an empty seat and slumped down, feeling like a snot-nosed, scuffed-kneed nine-year-old waiting to see the principal. Rows of people surrounded me, their faces blank, their eyes glazed. On the wall, a counter displayed a four-digit number in red letters. A number significantly lower than the one on the chit in my hand. I’d be there for a while.

I spent a few minutes grumbling to myself about the archaic ban on mobile devices. What could be the stupid reason? I’d already had to empty my pockets and pass through a metal detector to get into the room. What did they think I’d do with a phone? Snap pictures of my co-victims? Of the lovely clerks? Of the tottering piles of yellowing papers? Of the warning signs, the 20th century computers, the flickering fluorescents? Grumble, groan.

I fidgeted a bit in my uncomfortable chair, then I squirmed, then I examined at the boil on the neck of the man in the seat ahead of me, then tried to calculate if the glowing number on the counter was prime. I hadn’t had lunch yet so I spent a while listening to my stomach too.

Then I noticed a spray bottle of glass cleaner on one of the metal tables. I thought, that’d actually be interesting to draw. I had a pen in my pocket to fill out forms but no sketchbook. Then I remembered the neatly paper-clipped stack of papers in my lap. I flashed forward to handing over these documents to an official, papers now covered with drawings of Windex bottles and neck boils. No, I wants things to go smoothly and handing in my VIPapers festooned with junior high marginalia wouldn’t cut it.

I went back to looking at the bottle. I liked the way the neck curved into the body, the six concentric rings that were debossed into the plastic, the soft highlight in the middle, the way one square side of the nozzle was a slightly darker red that the next.

I decided to draw the bottle with my eyes. I coursed slowly along the edge, looking deeply just as I would if I were drawing. I made a run around the edge of the label, a contoured path with one continuous line. Then I jumped to the edge of the blue trigger, cruising into the hollows that fell into shadow, peering in to see every detail I could pull out. I trekked up the side, then slowed myself, not wanting to hurry too fast even though it was an unpunctuated stretch. Move too quickly, I told myself, and you miss something. I down shifted, making myself maintain the same pace no matter how dull the landscape.

A chair squeaked. I looked up, ten numbers had flipped on the counter. Still a way to go.

I moved to the boilscape on the pale neck in front of me. I uncapped my mental pen again and started to draw each hair surrounding it, the rivulets of sweat, the fold of flesh, the soft ridge of fat. I worked my way down to the yellowing neck of the t-shirt, then across to the right shoulder, then down to the sleeve, the arm, the top of the next chair, up the leather jacket of the man in the next chair, documenting each fold in the leather, then up the neck tattoo, across the lightly freckled shaven head, then up a column, over each poster, on the bulletin board, down the clerk’s handbag, over her bottle of Jergens, around the stapler and then a loud cough brought me back. My number was up. Forty-five minutes of my life had been compressed. I gathered my papers and approached the clerk on a cloud.

This morning, I sat in my kitchen. It was six thirty and the sun washed the room. I had been asleep five minutes before but I decided not to start this day by reading the paper and scanning my email.

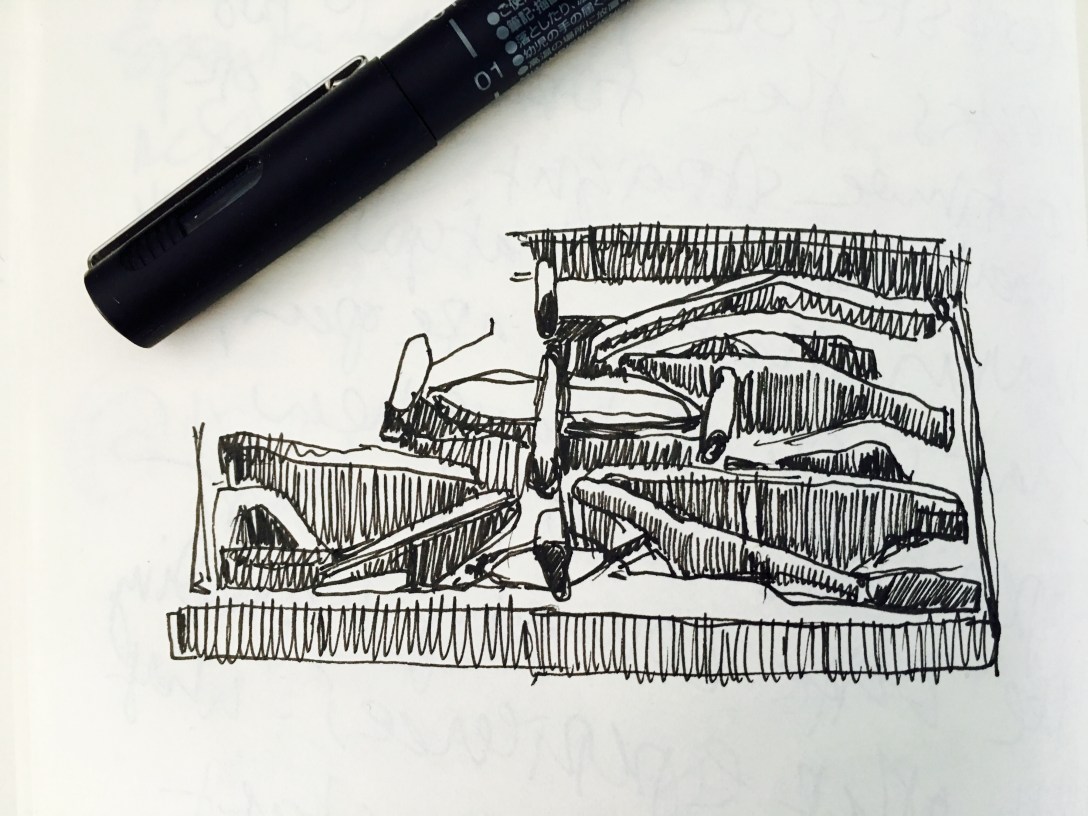

Instead, I went back to my moment in the temple of bureaucracy. I’d felt surprising peace there on my stiff-backed chair and it seemed it be a nice way to start my day, a little contemplation of nothing. I fixed my gaze on the top of my range, the burners and the bars that criss-cross the top, and started to trace the edges of the first one with my mind. The bars are black, so are the burner and the steel pan underneath, but the morning light made a hundred gradations of the curves and angles. The vertical bars stretch away from me, perspective forcing them into lozenge shapes The angled bars were cut by the bars in front of them so they formed jig saw shapes. I looked at each one in succession, working my way towards the back, increment by increment. The kitchen clock ticked away.

After twenty minutes, I had traversed the whole left side of the stove top. I slid my sketchbook over, uncapped my pen and spent the next twenty minutes taking the same trip, only this time I recorded the observations I made. At 7:20, Jenny came in to make coffee and the spell was broken.

I’ve never thought of myself as capable of mediation, but I think this exercise has a similar effect, slowing down and clearing my mind before the day begins and giving me a boost of creative energy that had me writing this blog post and sipping my morning tea.

I liked it. I think I’ll call it Omm-bama care.