When I started working with Keith, I was not in great shape. I had pains in my lower back, carpal tunnel syndrome, and chronic headaches. But I just grinned and bore these maladies. As far as I was concerned, these were just part of being me, aches and pains that I’d developed since I’d first started pounding on a computer all day, decades before — my imperfections, unfixable.

As for going to a trainer, well, that was all very well, paying someone to hold my hand while I walked around the gym, counting off reps, giving me encouragement, helping me build my biceps or lose a few pounds. Eventually, there were some meager results so I could take it or leave it.

Keith taught me otherwise. He showed the point of exercise is not six-pack abs or marathon times. It’s about making the most of the equipment we have for living out the rest of our days and that making certain little changes could make huge differences to my body and to my life.

We worked on tiny muscles hidden deep along my spine and between my shoulder blades. We focussed on the exact angle of my tailbone when I crouched, correcting and re-correcting. We looked at the angle of my pelvis in the mirror. We rolled the fascia alongside my left thigh with rubber logs and built up strength in my right quadriceps.

After a few months, standing and moving in a balanced way became second nature. The unnatural way I had held my shoulders, my neck, my stance, were replaced with alignment. Now if I hunched my shoulders or sat in a cramped and twisted way, my body told me something was wrong and I adjusted.

My headaches vanished. My hands no longer tingled. My feet, which had always splayed out like Charlie Chaplin lined up toe to heel. My carriage grew more and more erect. Jenny noticed that I was getting taller, soon by a couple of inches. I felt better all the time. And happier too.

For the first time, my relationship with my body changed because I saw what truly is. Not just a couple hundred pounds of annoying meat but an amazing machine that just needs to be tuned and maintained.

I discovered that my body is a miraculous system of complex interconnected processes that can be adjusted, honed, perfected. The way I was didn’t have to be the way I’d be. The unhealthy adaptations I’d made to certain chairs, desks, sidewalks, stresses, ways of standing, sitting, sleeping, were not carved in stone. And my assumptions about my physical being, that it was some sort of curse to be endured, an uphill battle that would always let me down, was nonsense. Being out of whack, behaving in ways that hurt me, limiting my ability, assuming that there was no solution — all these behaviors and thought patterns were replaced by balance and a better way of being.

For the first time, my relationship with my body changed because I saw what truly is. Not just a couple hundred pounds of annoying meat but an amazing machine that just needs to be tuned and maintained. Not for vanity but because of how it helps me live better and get the most out of each day. A few small adjustments in my body led to a change in my entire being. In my life.

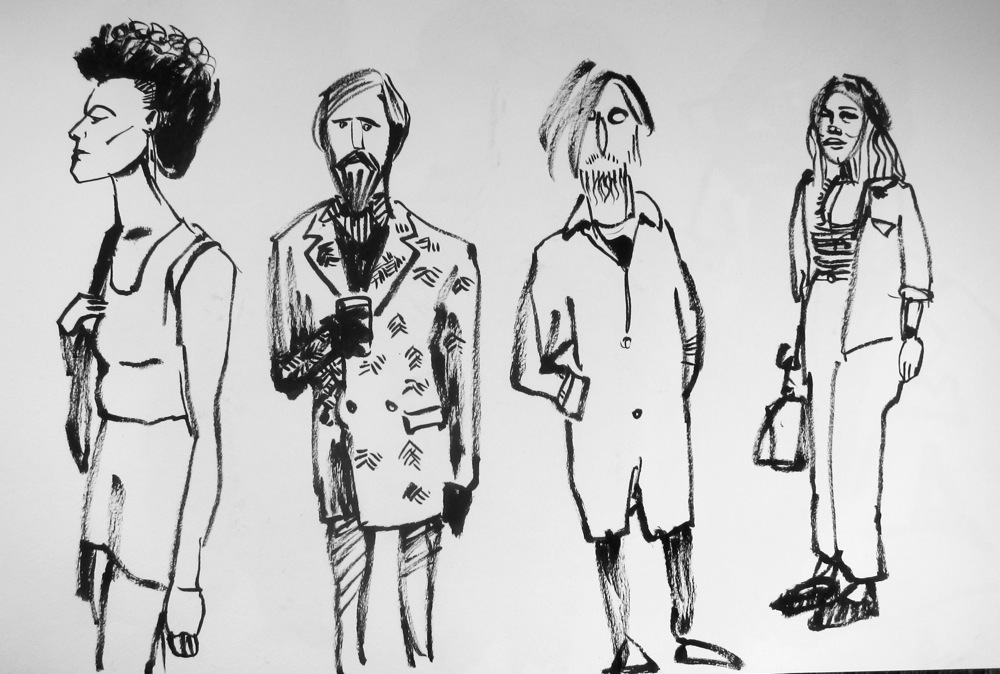

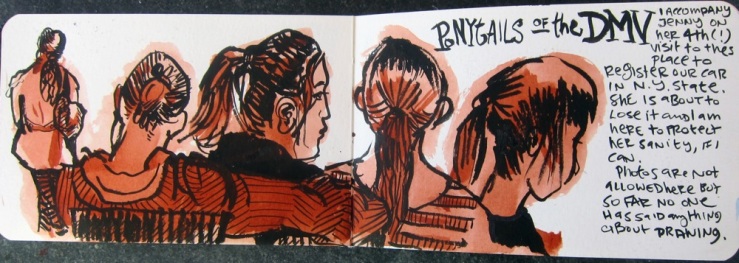

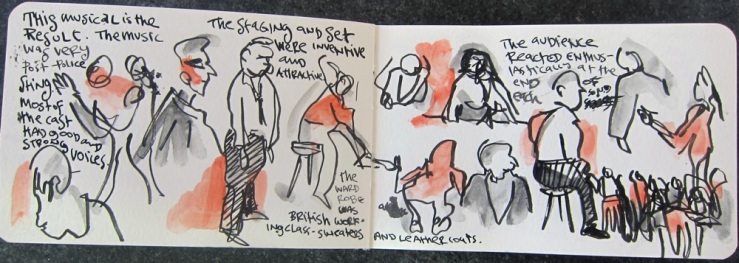

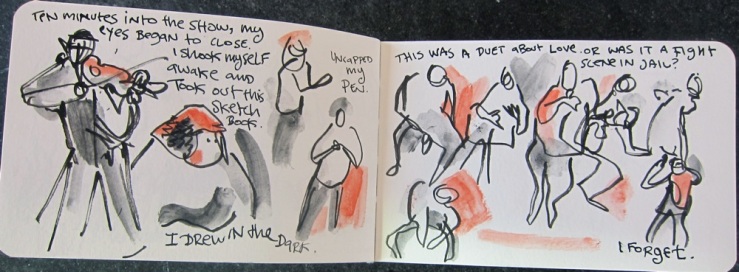

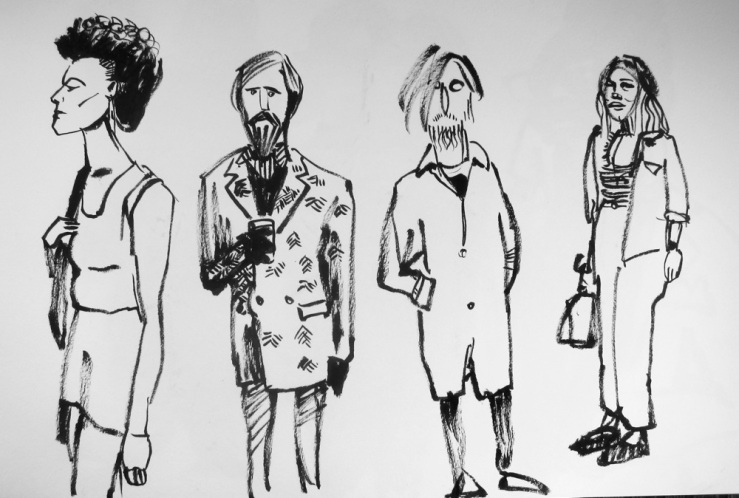

Similarly, when I began to draw, I had no idea what seismic shifts this small change would cause in my life. Many of friends tell me that picking up a pen and opening up a sketchbook ultimately led them to change careers, travel the world, publish books, make new friends, new priorities, new plans for their remaining days.

Why? Why does this simple habit make such a difference? When you start to draw, you set things in motion. You start to see what is. Perhaps you’ll see beauty where you overlooked it. Perhaps you will fill books with stories about your life, an ordinary life, and suddenly see it is actually quite rich and wonderful. And perhaps the power of seeing so clearly will make you want to go and see more. And that desire will cause you, like Mole in The Wind in the Willows or Bilbo Baggins, to lock the door of your cozy little life and wander out into the wide world.

Maybe seeing clearly will show you that you have been hiding your true self from yourself, have been leading a life that wasn’t really what you wanted, that you could do more, that you could be more. That your childhood dreams are still valid, that your parents, your banker, your boss, your children can’t call all your shots. And that time is running out.

When you make art, you slowly brush the cobwebs from your inner life and sunlight starts to stream in. Who knows what it might reveal?

Maybe you will see that drawing is a thing that you actually can do even though the monkey has too long told you that you can’t, because you suck, because you have no talent or time. And, when you discover this power, you may come to wonder what else you have overlooked or deceived yourself about, what else you can do and be. Maybe you could paint or play the piano or visit Rome or hang-glide or open a store or be a clown or run for Prime Minister. Or hire a trainer and get rid of your headaches.

This can be scary, feeling the first winds of freedom and change sweeping through the open door of your golden cage. But if you don’t face this fear from some angle, how can you ever see your life for what is and can be?

When you make art, you slowly brush the cobwebs from your inner life and sunlight starts to stream in. Who knows what it might reveal? Who knows what journey you are about to embark upon once you uncap that pen and take that first little step? Don’t you want to see?

ll yourself.

ll yourself.