I’ve been following a discussion on the Everyday Matters group and it has gotten my wheels turning. The talk has been about the utility of specific drawing assignments suggested by others, whether there’s really utility or purpose to everyone deciding to draw a piece of fruit one week, a pair of shoes the next, and then sharing their work and discussing it. While some people love it and have made it the main business of the group, others have complained that it has diverted the purpose of the group and distracted it from its original intention.

I’m not interested in taking sides because I think any sort of drawing is a good thing. However, I’d like to clarify what I’m up to with my drawing. While I have done some nice drawings here in Rome, I’m not interested in being a travel writer or an illustrator or a fine artist.

I want to live my life to its fullest and I find that drawing what I encounter deepens my appreciation. While I share my work with others, I make it for me. When I have unusual and interesting experiences like I’m having in Rome right now, my drawings seem to have a wider interest. But my core philosophy is that every day matters. Every single day. The day you meet the president. The day you have a baby. The day you find a special on sirloin at the supermarket. The day you get your shoes back from the cobbler. I find that drawing helps me to commemorate those events, large and small, dull and transformative. For me, that’s the point of art. To deepen my understanding of my life.

If someone else’s suggestion that I draw a particular thing opens my eye to fruit or glasses or the pattern of sunshine on my counterpane, then that’s great. But ultimately, we all live different lives and are handed assignments by each dawning day. Each day we’re handed a new set of challenges, new rivers to ford, new choices and wonders and pains and lessons. If we think the day is full and familiar, we need just dig deeper into it, look for fresh insight, peel back the layers of the onion. I find that drawing helps me do that.

Art lessons familiarize one with the tools but they are not a substitute for digging one’s own ditches, constructing one’s own nest. They are just abstractions and life is very concrete. I enjoy what I learn in life-drawing classes, but learn far more by drawing my wife’s sleeping body, my reflection in the bedroom mirror.

To draw, one must draw. Exercises and academic and books provide examples of what one might do, but experience is the real teacher. Take tomorrow as your assignment. Draw your breakfast, your bus stop, your bathroom wall while you’re shitting, your laundry as you fold it, your children as they watch TV, your pillow as you wait for lights out.

Be bold with your exploration. Capture what you do and have always done. Then push yourself to new experiences if only to draw them. Visit new neighborhoods and draw them. Meet new people and draw them. Try new foods, read new books, smell new flowers, do anything that will deepen your understanding and your appreciation of your world and your place in it.

I don’t care if you think your drawings suck, if you are ashamed to show them to anyone else. What matters is that you pause and contemplate. If your record of that contemplation is inaccurate, try again. Feel deeper. See deeper. Slow down. Relax. And tomorrow, do it again. You aren’t being graded or evaluated on your drawing. No more than you are being evaluated on your life itself. The only thing that matters is you. What you experience. How you experience it. How much you get out of this day and the next. This is your life. Dig into it. Embrace it. Notice its curves and angles. Explore its corners. Feels its edges and put them down on paper. The pen, the page, are just tools for you to take time and slow it down. I can’t make you do it my way, any more than I can force you to live your life my way. You decide, you forge your style, you pick the line that draws your life.

Take tomorrow and instead of hesitating and questioning and doubting and fretting, draw your breakfast, draw your day. Then try it again the day after. With each successive day, you’ll be clearer and deeper. If you miss a day, don’t freak out or beat yourself up. Just take on the day after that.

Share the results if you’d like. By sharing you will find commonality and support. But maybe you don’t need more than self sufficiency. In that case, keep your drawings for yourself. Or toss them out as you do them. The drawings don’t matter, the drawing does.

Tag: inspiration

The Art Spirit

“Genius is not a possession of the limited few, but exists in some degree in everyone. Where there is natural growth, a full and free play of faculties, genius will manifest itself.” — Robert Henri

I have always been a fan of Walt Disney. Not just of his animated films but of a certain image I have of the man himself. It’s not the dictatorial egomaniac that some biographers have depicted but the gentle, welcoming character who appeared at the beginning of each episode of the Wonderful World of Disney — small moustache, grey gabardine suit, warm smile, standing in his book-lined office.

When I flew home from LA for the weekend, I decided to re-screen one of my favorite videotapes for an infusion of inspiration. It’s an episode of the Disney show that I Tivo-ed a couple of years ago in which Walt answers letters from art students seeking direction in life. His advice to them is to read a book called “The Art Spirit” by Robert Henri. Henri was a painter and art teacher in the early part of the twentieth century, a terrifically inspiring guy who taught the generation of American realists that emerged in the 20s; people like Edward Hopper and Stuart Davis and John Sloan and Rockwell Kent, many of whom I like a lot. He encouraged his students to paint what they saw around them, urban scenes of everyday life — gritty, bold, and true. Henri’s students collected their noted from his lectures and assembled them into The Art Spirit and it has been a valuable guide for artists ever since, full of observations and ideas that are accessible and encouraging.

One of Walt’s correspondents asks him how he can develop style and Disney responds via Henri, with something like, “Don’t worry about your originality. You couldn’t get rid of it even if you wanted to. It will stick with you and show up for better or worse in spite of all you or anyone else can do.” To demonstrate how individual vision is really at the heart of style, he takes four animators form his studio, men who by day are paid to subvert their individuality in the service of creating a unified look for Disney movies and films them, of a Sunday, painting a tree. Each has his own way of painting, but more importantly his own way of seeing. One describes the tree in terms of architecture, like a solidly engineered structure on the landscape. He paints the tree as if it were made of steel pylons. Another artist is fascinated by the movement of the tree’s bark and studies the surface textures in detail. A third sees the tree’s relationship to the sky behind it and studies the negative space of the branches. A fourth observes the entire tree as unified shape and works on its relationship to the rectangle of his canvas.

Then we see how each artists interprets his vision in different ways through his materials. One paints of a big slab of plywood thrown down on a rock, painting with long brushes in a muscular way. Another draws in charcoal and then fills in with casein. When the paintings are done, they are juxtaposed and we can really see the varieties of worldviews in the four men. Even though they are talented artists, the real lesson comes from their willingness to put their own characters in their work.

It’s all shot in muddy black and white, typical old TV images, and the painters are not fine artists showing in NY galleries, just modestly paid artisans working for the Man. But the little film demystifies the process of art making in a wonderful way. It’s also a reminder of how the world has changed. Hard to imagine these days prime time Sunday night TV being devoted to something as ethereal as this. And the Disney Company, marred by well-publicized corporate battles and an surfeit of marketing and promotion, seems pretty far removed from the gentle art lesson on this show.

If you can, Tivo the Wonderful World of Disney, and see if you stumble on this gem. Or pickup a copy of The Art Spirit and be directly inspired by a great teacher. Try to keep in mind the wisdom of this thought from Robert Henri: “The object isn’t to make art, it’s to be in that wonderful state which makes art inevitable.”

— Written in a rental car in a rainy parking lot by the Rose Bowl, a few miles from the Walt Disney studios.

Chillin' with Dylan

Last week, I was hit by a sniffling cold midday. I spent the last few hours of the workday back at home, in bed with tea and Bob Dylan’s new memoir. By the next morning, I’d bounced back and finished reading the book.

For most of my life, I really had no interest in Dylan until about seven years ago when my friend, Bob Dye, more or less forced me to listen to The Freewheelin’ and Highway 61. The music softened my resistance but Pennebaker’s movie, “Don’t Look Back” triggered the sort of instant conversion usually limited to evangelicals. I haven’t paid much attention to the albums from the mid 1970s to the mid 90s but own and play most of the early and late records fairly regularly.

Despite all this enthusiasm, nothing prepared me for Chronicles, Vol. I. I had long assumed that , though I admired the music, the man was arrogant and withdrawn, the sort of person one would never want to spend ten minutes with. Instead, I discovered that Bob Dylan has all the hallmarks of the quintessential creative person (and I’m surprised that this surprised me).

First I was struck by how much he knows about music, all sorts of music, from classical to bebop to rap to doo-wop to the cheesiest sort of pop, and is able to extract something useful and inspiring from all of it. Like Picasso, he believed in borrowing from everywhere … but himself.

Secondly, he has always challenged himself — not to be successful financially and critically — but to constantly grow and branch out in new directions. Except for a period where he admits he was in some sort of creative stupor, he has always been motivated by some flickering notion in the back of his head that slowly grows and blooms as he feeds it. It’s not to ‘show the world’ or provoke the industry, but because he is always feeding himself with new influences that spark fresh ideas and directions.

Thirdly, despite the fact that he is such an important maverick, he has deep roots in those that came before. His love for and appreciation of roots blues and folks music has always been the core of his art. He has solid foundations, ones he forged himself, and he has been layering on top of them for fifty years. Reading about his early record collection had me revisiting mine, pulling out Sleepy John Estes, Dave Van Ronk, and Harry Smith’s American Folk Music once again.

Next, I was struck by his enormous generosity. He is lavish in his acknowledgment of all the influences on his art. He talks about what he learned from all sorts of surprising influences, everyone from Frank Sinatra, Jr. to Daniel Lanois.

It was fascinating to hear how he first came to write music, how content he had been to simply play others’ compositions, and how hesitant he was to compromise the body of folk music, sort of like if Horowitz began playing his own piano sonatas rather than Ludwig Van’s. Slowly Dylan began to introduce his own additional lyrics to folk standards and then eventually to create his own from the staff up.

While he was committed and hard working, Dylan never comes off as terribly ambitious. He wants to keep moving forward, to play for larger audiences so he can have new creative opportunities but he never set out to be a superstar. In fact, in his admiration for pop singers and Tin Pan Alley composers, he acknowledges that playing Woody Guthrie songs hardly seemed the road to fame and fortune, even in the folk-mad days of the early 1960s. Even recently, when he has been touring a lot, it’s to stretch himself creatively, to play music publicly that should be played, to shed the nostalgic classic rock trappings and talk to new audiences in new ways. Miles was much the same way. The still-touring members of the Stones, the Beatles, the Who, etc. have no such creative ambitions.

I’d urge you to read the book and see how it strikes you. I believe it has a lot in it for anyone contemplating their own creativity.

——————

A number of people have written to me for a certain kind of advice. Typically, they’ll ask how they can become professional illustrators or, even more frequently, how they can get books published. I tend to answer such letters less often than I used to because I realize that I don’t have the answers. But I think Bob does. Here are a few landmarks:

1. Figure out what you’re about. What do you like to do, what are your media, your subject matter, your style.

2. Explore. Getting to #1 requires flexibility, openness, a willingness to explore and to try on lots of costumes.

3. Focus. Spend less time on success and more on art. The more you work, the better your art, the more likely things are going to happen. And figure out what you really want. At one point, I just wanted my name on a book jacket, any book. Now I have a clearer sense of what I am willing to spend my time on. And consider your work from the point of view of those who you want to want it. Learn about the industry you are trying to break into and the audience you are talking to. Don’t just send off stuff to inappropriate and uninterested publishers. Understand the market.

4. Move to New York. You may have to make some sacrifices but if you’re not where it’s at, you’re not where it’s at. This applies to those hellbent on commercial success (but, of course, there are many other ways to be successful). But most importantly, when you are in the deep end of the creative pool surrounded by others full of energy and ideas and examples, you learn to swim a lot better.

5. Be generous. Seize every opportunity to thank people and include them in what you’re doing. Give your work away then make more.

6. There are no small parts. Play the coffee shops, pass the basket, don’t just hold out for the Garden. Be willing to illustrate school play programs or diner menus, publish a zine, start a blog etc. whatever will get your work out into the world.

7. Meet like-minded folks and be actively involved with them. Meet other artists and creative people but don’t just talk about the business of art (god, how dull) but share your passion for making things and infect each other.

8. Never complain, never explain. Be yourself and be glad of it. Creativity needs light and nourishment.

9. Above all, do what you love and love what you do. Don’t try to figure out what you should to to be successful but how to successfully express what’s makes you you. There’s nothing more pathetic and boring than those who have done everything they can to mold themselves to the prevailing notions of what is popular. That already exists (it’s on Fox and it’s called American Idol). You need to blaze new paths, your own paths. No one does what you do. Keep it that way by expressing the true you, the inner you.

Remember, Art’s most important job is to light the viewer’s fuse, to create new feelings and insights, to create by sharing. By sharing yourself, you make the world a better place. The important goal is not to win gold records or Hummers or groupies. It’s the same as the goal of every share cropper who picked up a Sears guitar and wailed the blues. To be authentic, to express yourself. That may lead you to Cleveland and the Hall of Fame or, even better, to an enriched feeling of what it is to be human.

Idol worship

I was about fifteen and my idol was Eric Drooker. He was in the eleventh grade, the first boy in school to have an earring, to wear black Danskins and clogs and eyeliner and modeled himself on David Bowie. We would hang out at his place in the East Village and talk about comic books and girls and listen to Frank Zappa records. Over his bed, Eric had a bookcase full of underground comics in individual plastic sleeves. Before long, I shared his obsession with Robert Crumb.

I was about fifteen and my idol was Eric Drooker. He was in the eleventh grade, the first boy in school to have an earring, to wear black Danskins and clogs and eyeliner and modeled himself on David Bowie. We would hang out at his place in the East Village and talk about comic books and girls and listen to Frank Zappa records. Over his bed, Eric had a bookcase full of underground comics in individual plastic sleeves. Before long, I shared his obsession with Robert Crumb.

Crumb was bold, scandalous, loved old records and voluptuous women’s bodies, hated the hypocrisy and materialism of American culture, and drew like an angel. We studied his crosshatching and adopted his spelling and his politics. It’s an obsession I’ve continued to feed for thirty years, though my Crumbiana is all dog-eared and well thumbed rather than in pristine collector’s condition.

Eric went on to publish his own graphic novels and draw covers for the New Yorker and I’m sure people keep his work in plastic bags of their own now. You can check some of it out here. My own path was more humble.

However ….when we talked to Crumb tonight (he and his wife Aline are visiting NY from their home in the South of France), Patti asked him, “What was the best butt you ever saw?” which threw him into a paroxysm of revery and he waxed eloquent about Serena Williams. To me, he said “I love Everyday Matters. Thanks so much.” and my fifteen-year-old self died and went to heaven.

Now, I wonder, is his signed copy of my book in a plastic sleeve?

Notes from a chat with Julie Dermansky

Julie Dermansky: Journal page – European monumental architecture

Julie is one of my favorite artists and she has always been a huge source of inspiration and encouragement to me. She is so committed to making art and has a lot of experience in how one survives financially and psychically as a creative person.

JULIE: Inspiration is overrated. It’s all about discipline. There are glimmers of inspiration, when you lose touch with time and place but you can’t wait around for that. When I start working on something where I am so excited it’s like some sort of drug, I’m just alive. But the only way to get there is through discipline.

It doesn’t matter why you make art, you’ve just got to make stuff and eventually you’ll understand. I won this grant that allowed me to travel for a year. I just had to write four letters back to the foundation over that year. That was it. I was 20 and I could do whatever I wanted. So I just made drawings in my journal, drawing monumental architecture all over Europe. That was my only discipline, my commitment to do at least one drawing every single day. And because the fancy journal books were too expensive, I made my own, ripping up water color paper and tying it together. It evolved as I went. And when a book was filled, I would send it home and I had no idea what the value of what I was doing could be until I came home and saw all those journals. It came out of me with no forethought and I’d never done it that way before. It just came out that way. I didn’t worry what people would think, I just tried to be honest. And I didn’t worry about the quality of the drawing, I just went with it. I hated having a page I didn’t like so I kept working it until I liked it. Those pages are so vibrant and visceral, so raw. I don’t know if I can get back to that looseness, pure hand /eye. The more time I had the more I let go, the looser, the better it all got. That art was my reason for getting up each day. For me, travel is a lot of work. Nothing planned, figuring everything out on the fly, real work.

Julie Dermansky: Steel Gate at her studio in Deposit, New York

Julie Dermansky: Steel Gate at her studio in Deposit, New York

JULIE: I was at the art students league taking drawing and this teacher came behind me and I was making a mess like I do and he said “Ah, a lefty. But its nothing like Rembrandt,” and I was, like, “Rembrandt? Fuck you! Why would I draw like him? He was great but he already drew like that. I’m not here to do that.”

If I can recognize something you did without being told you did it, you have done something magic, you have created a visual vocabulary. Good, bad, doesn’t matter you’ve created something brand new. Everything’s been tried but no one can draw like you, unique, special. It’s not the materials, it’s you.

Everyone can multiply. You struggle at algebra but you can learn it. Everyone can draw. Everyone can do their times table. It’s just a matter of developing the skill. Drawing is a skill and a science, like learning perspective.

I love Tennessee Williams – At the beginning of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof., he says something like “Every human being is in their own jail call and all we can do to communicate is to take the thing you know the best and put it out there. The strongest part of you that everyone can interpret in their own language.” He took his internal dramas and made works of art that are in the mainstream yet retain that rawness. You don’t need to know all about his internal extremeness to enjoy his work.

I don’t know why I make the things that I do and I don’t overanalyze it. I never took formal art education classes, I learned it from art historians, composition, color theory, I learned it right from the work, not from academics.

There’s work I’ve done that was completely derivative and I wouldn’t show it. It’s not part of my vocabulary. It’s my homage to the artists I love.

If you go to a museum or a gallery and you have to read the thing on the wall to understand the art, the work is bullshit. However if you go that museum and have some sort of response to the work you can’t understand, and then you read the wall, and reading the explanation helps you develop another layer of appreciation and understanding, that makes the work more rewarding, it will be a beautiful thing.

I went to see the Calder retrospective at the Whitney when I was in second grade. And I appreciated that he is a great artist but I just didn’t like it and it bugged me and I said to myself, I can make better things than that and I knew that I would. I was that confident as a child. Then looking at Picasso, I thought how did he make so many pictures and then when I really started rolling with my own stuff, I said, Oh, if you make work everyday it’s not that hard to make that much stuff. I just compared myself to the pros and never found that conceited. In Europe, it’s very conceited to say ‘I’m an artist’ but it’s fine to say ‘I’m a painter’ or ‘I’m a sculptor’.

For me the definition of an artist is someone who has created a visual vocabulary. I may not like it. But when you look at a retrospective of an artist’s work, you can check it and look for the vision, the palette, even if you don’t respond to it. It’s not about liking but seeing quality, consistency.

Julie Dermansky: from the Lumis Collection in the basement of the Robinson science center, Binghamton, NY

JULIE: My work isn’t really done until it’s out in the world.

My uncle is an artist and told me, never sell anything for less than say $100, or make up your own number. If it’s less than that number, then just give it away. But don’t sell it. I like that rule. Keep the value for yourself. Joseph Cornell hated to sell his stuff. Leo Castelli could never get it away from him.

Andy Warhol said make pictures you’d sell for $100 and others you’d sell for $10,000. That way you just get your work out there by having something for every budget.

Some people feel the universe should take care of you, and others get out there and hustle.

There’s always a way to make money, one way or another. I grew up around the drive to make it for its own sake but for me it was a way to be an artist. Being an artist costs money and I needed money in my pocket. I started making and selling jewelry when I was 14. In college, I would go to the dorms, not be shy, just say, “would you like to see some jewelry” and spill it on the bed. I’d make $400 or $500 which made it pretty impossible to go do some job for $6 an hour. It didn’t make any sense. My art objects always sold.

I’m not qualified to do anything so it’s lucky people have always bought my stuff.

People romanticize self-employment but it’s a heavy burden because you can’t count on regular money coming in. I’ve envy people with steady jobs on one level. I have no safety net but then again no one is 100% safe and the rug can be pulled out from under anyone.

A lot artists don’t do their homework. You have to hustle, have to keep going, Have to have faith in your work. You have to be willing to go below your level sometimes without bumming out. If you insist on selling everything for thousands and never do, you’ll end up with no money and no collectors. If you need the money, don’t feel bad, get your work out there. That’s what makes your work into a commodity, because it’s visible. I don’t know who created the rules about artistic integrity, that money is evil, that you shouldn’t make work in order to sell it, that it shouldn’t have a decorative element. And no art schools have classes about marketing. It’s frowned upon.

It’s so easy to give up, to forget to market, to forget to find a market place, to not do your homework. You’ve got to feel confident about your work, that’s a key to salesmanship. You’ve got to learn about grants and sources of funding. Artists have a knack for being self effacing and for being overly self critical instead of learning skills and promoting themselves.

The art world is very seductive and full of hangers-onners. there’s so much energy and people want to latch on to it. When I’ve had relationships that have reached the point where men say you’ve got to decided between me and the work, it’s too much and there just wasn’t a choice for me, of course, it was the work.

I can’t be something else, even if I wanted to.

To see more of Julie’s work, please visit her website.

Cross Country

I have just returned from a cross country trip to visit some of my journaling friends.

I have just returned from a cross country trip to visit some of my journaling friends.

My first stop was in Minneapolis where I spent several days with Roz Stendahl whom I first encountered through the 45 wonderful journals she kept documenting the life of her dog, Dot.

Roz is a designer, illustrator, teacher, and writer who has been enormously generous to me with her time, advice and friendship.

Roz has been teaching me a great deal about pens and watercolors and I was anxious to see her studio. She has every conceivable type of paint and brush, marker and pencil, not to nention 3,000 rubber stamps in a painfully orderly library. My current journal was bound by Roz with 140lb. Arches watercolor paper and a hemp canvas cover. It was terrrific to work in and I have really been enjoying working in a book with landscape proportions once again.

Spending time with such a dedicated, prolific, fastidious, creative and talented artist was a great treat. I was really happy with just about every drawing and painting I did in Minesota and it was largely due to Roz’s example. She’s so full of energy and ideas that I really wish I’d had another month to visit with her.

Our drawing trip began at a hilarious junk store called Axman filled with my favorite sort of drawing subject – intricate gizmos. I couldn’t make up my mind what to tackle until I saw Roz and her mini paint box hovering over a gas mask.

Next we headed to the Minnesota zoo and turned ourselves into major attractions by drawing various critters. Roz draws standing up so I joined her and foud it quite comfortable though it was a little tricky propping up my paint box and my pub towel and all.

Next we headed to the Minnesota zoo and turned ourselves into major attractions by drawing various critters. Roz draws standing up so I joined her and foud it quite comfortable though it was a little tricky propping up my paint box and my pub towel and all.

I’ve never drawn at the zoo before, thinking it would be impossible to capture moving animals but I discovered that they tend to assume a handful of positions and if you keep a bunch of drawings going at once you can go back and forth between them to capture the different positions. we draw a bunch of beavers in an overly chlorinated pond. One of them scratches himself with feverish determination.

Roz is a prodigious notetaker; she speckles her drawings with all sorts of observations about her subject, writing down colors, behavior, funny things passers by say to each other.

I tried to emulate her but all of my notes tend to be a string of jokes instead. But I do love the look of hand writing and drawings together.

It’s quite amazing how people just zoom past exhibits, checking off the animals they’ve seen as if it was a competition. If they linger, it’s often to say something mind-blowingly ignorant or mean, particularly the adults.

It’s quite amazing how people just zoom past exhibits, checking off the animals they’ve seen as if it was a competition. If they linger, it’s often to say something mind-blowingly ignorant or mean, particularly the adults.

Drawing them makes me appreciate the incredible miracle theses beats are and how extraordinary that they are right here in front of me, in Minnesota.

It’s so intimate to be just on the other side of a thin sheet of glass watching a slumbering lion. I was no more than a foot from him; I could have taken his big soft catcher’s mitt of a paw in my hand and felt the coarse hair of his beard were it not for the window.

It’s so intimate to be just on the other side of a thin sheet of glass watching a slumbering lion. I was no more than a foot from him; I could have taken his big soft catcher’s mitt of a paw in my hand and felt the coarse hair of his beard were it not for the window.

After two zoos, we decided to check out some cadavers. I love natural history museums and Minneapolis’s is a pip — the specimens were posed in wonderful dioramas with wax leaves and meticulous details. I enjoyed standing close so the painted backgrounds filled my peripheral vision and I could imagine that I was standing in the forest with wild beasties. It was a nice change to draw a critter that wasn’t going to turn around and scratch its butt, lick its genitals or wander behind a tree in mid-drawing.

We were basically the only visitors looking at the taxidermy and, after drawing this sheep, I took a nine minute nap on one of the hard wooden benches. The museum also had a touchie-feelie exhibit where you could pet taxidermy and toss skulls around so we drew a few of them.

My time with Roz and Dick was running out; I took pictures of her voluminous collection of hand-bound journals, we ate dinner at an Afghani restaurant, and the next morning I began the most arduous leg of my trip, flying to San Jose, connecting to Portland and then renting a car to drive 300 miles across Oregon to visit my pal, d.price.

Here are a few more souvenirs from Minneapolis. I so envy Roz her neat and orderly studio. What you don’t see are the big computer/scanner/printer end of her studio as well as a second room crammed with journals, research materials, bookbinding stuff, and some 60 drawers full of boxes of rubber stamps. Heaven!

Upon arriving in Portland, I began the longest drive of my life, across Oregon. I am a native NYer and don’t drive much so tackling the endless, dead straight roads of the West was a new and somewhat daunting experience.

I broke the trip in the small town of Pendleton, bought myself a magenta cowboy shirt, and checked into a wee motel. The next morning, I headed out at 7 a.m. and promptly got my first ever speeding ticket.

From my letter to the judge:

Dear Judge Dahl:

On August 19, 2004, I received a traffic ticket (#32914) for driving over the speed limit. While I do not deny that I was traveling at the recorded speed, I would like to explain some of the circumstances to help you reach a final decision on the matter.

This was the first time I have driven in Oregon. I live in New York City, NY and was driving across state in a rented car. I had just come off Rt. 84 (where the speed limit is 65) and onto Rt. 82. The roads were fairly empty at this early hour of the morning and very straight. I have never driven in the West before on such long straight, sparsely populated roads and, after driving 200 miles from Portland in an unfamiliar vehicle, I did not gauge the appropriate speed properly. I have been driving for over twenty years and have never received a speeding ticket before, so I hope you can appreciate that this sort of driving is certainly not a habit with me. I’m sorry for any inconvenience I may have caused you, the officer or the State of Oregon but can assure you that I will never drive in this manner again.

I enclose a check for $237 but hope that you can see your way to reducing my fine.

Yours,

In a state of shock and high anxiety, I finished the drive and pulled into Dan Price’s little town, Joseph. After a restorative cup of tea, we headed over to the cemetery where d.price is the groundskeeper.

Joseph has an interesting blend of residents. There are cowboys and construction workers like you’d expect in a small Western town. There are also several bronze foundries so a healthy art community has sprung up. There are aging hippies and young anarchist freaks. And there are a few very rich folk, some quite mysterious.

Dan’s friend Dave is one such millionaire and the source of his money is of endless intrigue to his neighbors. I proposed that he might be D.B.Cooper — he hijacked a plane in the early 1970s and then parachuted out over Oregon with the ransom and was never found. Dave collects planes and loves ultra lights. We drew this one in his hangar at the Joseph airport.  On Saturday, Dan assembled a group of local artists for a drawing get-together. We breakfasted at the Wild Flour Bakery and shared journals, then headed out to the Kooch’s farm to draw stuff. As usual, it was great to draw with like-minded folks.

On Saturday, Dan assembled a group of local artists for a drawing get-together. We breakfasted at the Wild Flour Bakery and shared journals, then headed out to the Kooch’s farm to draw stuff. As usual, it was great to draw with like-minded folks.

It is so different here from my life. Everyone knows each other and there’s endless gossip. The pace is gentle and free and open-minded. I don’t know if I could stand small town life for long but it makes a great break.

Last winter, Dan Price’s son, Shane, volunteered to make a sculpture of his school’s mascot. Dan offered to help. Before long, the project has mushroomed, the eagle was seven feet tall and, while Shane put in a couple of hours here and there, Dan was working ten hours a day on this massive bronze bird. Neither of them had ever welded or sculpted before and they used the welding test scraps from the school’s metal shop as their raw materials.

After several months of herculean effort, the bird was unveiled at graduation and it looks like it’s been there forever. A family of yellow jackets has taken residence in a klieg horn between the bird’s scapulae.

The highlight of my visits to Oregon is always staying in Dan’s place, Indian River Ranch. Over the past decade or so, he has lived on a meadow on a river bank and had erected various sorts of residences there. He has lived in a teepee, in a one man tent and then built a kiva, an underground structure like a hobbit house. You enter through a knee-high door and crawl into a wood-lined burrow, a round room about seven feet in diameter. It has wall-to-wall carpeting, electricity, a sky light and is always 55 degrees, year round. I always sleep like a hibernating squirrel in there.

The meadow contains other buildings: a garage for Dan’s trike (he recently drove it 5,000 miles across country) ; a little kitchen/shower; a sweat lodge; an outhouse; and his most recent construction : a fantastic boulder covered studio where Dan publishes his zine, Moonlight Chronicles.

The meadow contains other buildings: a garage for Dan’s trike (he recently drove it 5,000 miles across country) ; a little kitchen/shower; a sweat lodge; an outhouse; and his most recent construction : a fantastic boulder covered studio where Dan publishes his zine, Moonlight Chronicles.

(If you don’t subscribe to it yet, I’d be very disappointed. It inspired me to start drawing, journaling, and get on the path I’ve been on for years. It is a mixture of adventure, philosophy and art that will make a serious impact on your life. I simply insist you subscribe right now. Come on! It’s inexpensive and wonderful! Or at least download yourself a copy of your license to be a kid).

The meadow has a lawn, a vegetable garden, and a couple of acres of wilderness. It is a Walden-esque paradise.

I have created a special gallery of images from the meadow. I hope they bring you peace.

We finish up our sketching for the day and pack up the car for the hour drive to LaGrande where Dan’s parents live, stopping en route to pick a bouquet for Joanne Price.

We finish up our sketching for the day and pack up the car for the hour drive to LaGrande where Dan’s parents live, stopping en route to pick a bouquet for Joanne Price.

The Prices have a large bison ranch and I drive out with Dan’s dad to visit the herd, about a hundred of these monsters and their families. Dan’s mom is an accomplished pianist and after dinner she plays beautiful music as I draw. The serene evening is jarred by the abrupt and uninvited arrival of Dan’s ex-wife, Lynn, who, as is her wont, causes a scene. Nonetheless, I sleep well and head out early for the long, leisurely drive back to Portland. No speeding tickets this time!

Last stop on my cross-country trip: the Mission district of San Francisco to visit my e-pal, Andrea Scher. If not for Andrea, this blog wouldn’t exist. Last December, she convinced me that I could and should start a blog of my own after I showed admiration for her site, Superhero Designs, a combination jewelry showroom, photography gallery and creative coffee klutsch.

We spend a couple of days walking around her neighborhood, drawing, shooting photos (she also convinced me to buy my wonderful new Canon Rebel digital camera), and talking about art, commerce, and her time working for SARK. Andrea is wise beyond her years and has given me so much sound and illuminating advice. Like many young people and creative and sensitive people she is still looking around to define her own identity, to figure out what she should do for a living, how to make ends meet without surrendering her spirit and her creativity.

We spend a couple of days walking around her neighborhood, drawing, shooting photos (she also convinced me to buy my wonderful new Canon Rebel digital camera), and talking about art, commerce, and her time working for SARK. Andrea is wise beyond her years and has given me so much sound and illuminating advice. Like many young people and creative and sensitive people she is still looking around to define her own identity, to figure out what she should do for a living, how to make ends meet without surrendering her spirit and her creativity.

For a weird West Coast experience, she took me to Psychic Horizons for a psychic reading. An intense looking man examined my aura and told me that he saw a floating glass vial of red liquid that indicated that I had a substance abuse problem. All I could think was that perhaps the vial represented ink, the only substance I indulge in with any regularly. Then he cleaned my chakras and filled my being with an imaginary pink liquid filled with golden flecks. I felt rejuvenated and my walled was lighter by ten bucks.

There was a madonna in the psychic courtyard and, to avoid being ensared in conversation by any of the inmates, I drew and Andrea photographed her.

“Mi Casa”

When I was in San Francisco, I stayed in a little guest house called “Balmy Casa” . It was a lovely apartment that even came with two bikes to rise up and down (puff) the hills of the Mission. My favorite thing was the street, every house of which was covered in spectacular murals. There is street art all over the neighborhood and, on one morning, I saw no fewer than four artists at work on fresh ones. New York has occasional murals but they are are rarely well done and quickly desecrated. In SF, the art makes the street glow. If I wasn’t so in love with NYC, I would definitely be packing for ‘Frisco town.

I took a few pictures of my neighbors’ digs to share with you.

Meet Prash

Every so often I see work that makes me say, “Well, yes, that’s what I’m trying to do but some thing seems to have interfered between my brain and the page.” Prashant Miranda’s journals always make me feel that way.

Every so often I see work that makes me say, “Well, yes, that’s what I’m trying to do but some thing seems to have interfered between my brain and the page.” Prashant Miranda’s journals always make me feel that way.

He emails me tantalizing glimpses from them every so often and I get quite green with envy. His watercolors are so loose and bright and expressive.

Prash came to Toronto from India some five years ago. He says: “if I was to describe myself…i’d say that I am a scribe. I keep sketchbooks all the time, it’s moved from sketchbooks to sketchboxes…with loose pages, and now they are leather pouches that I stitch myself.”

Prash has sent me journal pages he made in India: on his recent visit to Quilon, his childhood home on the south west coast of India, and of the lighthouse in Tangeserri; to Benares, the holy city in the north; and to Goa. And also scenes from Canada, his new home: his solo camping trip on an island in the Moose River; and, most recently, an old sedan being being shot in his neighborhood for the Russell Crowe movie, Cinderella Man.

Prash worked for Cuppa Coffee, a lovely animation studio where he’s developing a kids’ show called Ted’s Bed. The series looks to be an updated version of Nemo in Slumberland and the website is full of watercolored postcards with beautiful calligraphy in Prash’s signature style.

If you’d like to know more about Prash, drop him a line.

Miles ahead

I’ve been reading about jazz recently, specifically about Miles and his seminal album, Kind of Blue. Miles was intensely committed to what he did, brave in a way I wonder if I can ever be. He seemed to live without doubt. At one point, he and the author had an argument about what day it was. When he was shown a copy of that day’s paper, proving he was wrong, he said, ” See that wall of awards? I got them for having a lousy memory.” He didn’t dwell on the past, didn’t repeat himself, did what he did and kept on forging ahead.

I’ve been reading about jazz recently, specifically about Miles and his seminal album, Kind of Blue. Miles was intensely committed to what he did, brave in a way I wonder if I can ever be. He seemed to live without doubt. At one point, he and the author had an argument about what day it was. When he was shown a copy of that day’s paper, proving he was wrong, he said, ” See that wall of awards? I got them for having a lousy memory.” He didn’t dwell on the past, didn’t repeat himself, did what he did and kept on forging ahead.

What keeps one so resolute? Miles was successful, rich by jazz standards, but he was derided for how he behaved. People thought him arrogant, racist, mysoginistic, and uncommunicative. He would often play with his back to the audience and never spoke on stage. I don’t believe he behaved this way because he could. I think he was just being uncompromisingly himself. That was the key to his art. He was an asshole, but that was okay with Miles.

How do you learn from a person like this? How do you follow his example in order to become purely yourself? Does it mean being unresponsive to any input, being pigheaded, selfish and rude? Of course not.

Miles believed in his art. His commitment was complete and he worked enormously hard on his technique and ideas. Even if he wasn’t right (and by and large he was), he could tell his inner and outer critics that he did his very best and that he had faith in that . Perhaps that’s the point of one’s life. To discover what one loves, to pursue it to the utmost of one’s ability, and then to gauge the success of one’s life by how purely one has done that, rather than by the criteria others set.

It can be a rough road. One can struggle to make a living. One can fail to get accolades or even support from others. Personally, I wouldn’t be satisfied with a life that offended and alienated the rest of the world but maybe I am just a pussy. Still, I think if you can sustain Miles-like focus on your art, your chances are good. Van Gogh spent a decade drawing crap, but he kept at it, and then suddenly blossomed.

I’m sure many people will say: “Are you telling me that if I work hard enough, I will succeed? And conversely, if I don’t achieve the heights, it will be due to my lack of sustained effort?” I don’t know. I don’t want to paint such a black and white picture. But I think focus and perseverance are critical. The thunderstruck artist, whacked by the muse, and suddenly a huge hit, is a myth. You’ve gotta practice and practice and practice to bore to your core. Then you’ve got to have the bravery to be unflinching about exposing that core. You’ve got to be smart, figuring out ways to share your work with different people who will give productive advice and help share your stuff with others. It helps to be lucky (whatever that means).

And I believe that a positive outlook is essential too. That takes work as well. I am often my own worst enemy, my inner critic baying at every shadow. I can wake up at 4 am and keep myself awake with horrible images of my ‘inevitable’ fall from grace. In my churning mind, my foolish ways destroy my family, my savings, my health, my promise. Instead of being a grownup, I am dabbling in feeble, artsy things. Unwilling to suck it up and just do my job as a man and a provider, I am indulging myself in crap like this blog.

But, when I wake up, exhausted from the assault, I try to get to work to paint a sunnier picture. The fact is, I have dealt with harder things than nightmares and nagging internal voices. And I have done that by being positive and proactive.

The future is a blank sheet. I can try to catapult shit at it but that’s just making the present uglier. And a long succession of ugly todays will lead to an ugly tomorrow. On the other hand, I can impact the future by believing in myself, by working hard, by staying the course, by confirming my directions with those who have already travelled it, by purifying my expectations and intentions, by keeping my chin up.

Maybe Miles wasn’t actually all that confident. Maybe that’s why he put shit in his arm and up his nose, why he raged and sulked. But I know he was positive about his art. If he hadn’t been, he would still have had all that doubt and stress. But he wouldn’t have Blues for Pablo and Bye Bye Blackbird. And nor would we.

Ten thousand things to draw

Content of kitchen cabinet, fridge, bedside table, medicine cabinet

Content of kitchen cabinet, fridge, bedside table, medicine cabinet

All my shoes, clothes

Covers of ten favorite CDs, books

Every significant front door of every place I’ve lived or worked

Everything I eat today

Contents of my bag, of my pockets

Every tree on my block, labeled with its official Latin name

All the cars on my block

Views out each window in my home

Clutter on my desk

A map of my neighborhood

A map of the house I grew up in

Portraits of my wife, son, and pets asleep

Every appliance in our house

Every phone in our house

Series: every cup, mug, vase and lamp

My hands, feet, face, body

The exterior of each place I buy lunch

My car’s engine

Every pen and pencil in my desk

All of Patti’s cosmetics

Every present I got on my last birthday, Christmas

All of our sports equipment

Every chair in our house

Every outlet and all its plugs

Everything that belongs to a pet: food, toys, clothes, bed, medicine, cage, etc.

All the liquor in our cabinet

The portraits in my yearbook

Ten pieces of broken cookie

Ten manhole covers

Ten hydrants

Each component of a sandwich, individually, then assembled

All our jewelry and watches

Every hat I own

Every bill and coin in my pocket

Ten things from any catalog in our mailbox

A plate of spaghetti

The laundry: clothes, machines, detergent, etc.

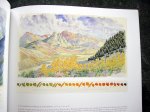

Inspiration Journal: Tony Forster

This guy is scarily good. Tony Forster’s watercolors depict his treks around the world, to the rain forests of Costa Rica, the volcanic island of Montserrat, Bolivia’s mile-high lakes, the slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the scorching desert of Death Valley. I first saw them in a froo-froo gallery, stopped dead in my tracks on Madison Avenue, thinking “Wait, wasn’t I supposed to have made these, y’know, in some parallel universe?” On the edges of his gorgeous landscapes paintings (he paints on sheets of watercolor paper, usually 22″x31″), he attaches little sample swatches, topographic maps, and then stencils, types, and hand writes notes. This softcover book of his work was published by the Frye Art Museum in 2000.