Why do you want to start drawing?

Wait, let me rephrase that — you probably don’t want to start drawing. You want to be be really good at drawing.

To pick up a pen, grab some paper, and effortlessly draw anything, perfectly, beautifully, dazzling your friends and confounding your enemies. You want to be the next daVinci, to knock out portraits indistinguishable from photographs, to replace your vacation snapshots with breathtaking watercolors, to have gallerists, collectors and reviewers clamoring outside the doors of your sunswept Tuscan studio. And you have to start somewhere.

But deep down, you fear that you’ll never get to be great. It’ll be too hard, you’ll just give up, and instead of pride, you’ll be besieged by self-recrimination. Your dust-covered sketchbook will be just one more reminder of your failed attempts to achieve your dreams.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Seriously. Here’s how I know. I’ve been helping folks to start drawing for ages but more importantly, I have helped myself to start drawing. And by teaching myself, I have learned a few things that could help you to get past those first few challenging steps. So this story is less about drawing techniques than it is how to incorporate drawing into your life, how to keep yourself motivated, and how to learn to learn.

How to accurately measure progress: So many fledgling artists focus on the horizon, then trip over their own feet and fall flat. They began by focussing on the end result of learning, that perfect drawing, then despair when each line they make fails to achieve that goal. What they are overlooking are all the individual steps they are making towards that objective, the small but crucial improvements they are making every day. I know this because it happened to me too. Early on, I’d flip through my first handful of pages and grimace. They all sucked. I sucked. And I’d never get any better.

But, had I been paying attention, had I been willing to be objective instead of brutally critical, I would have noticed how much actual progress I’d been making. That my lines were more confident. That I’d tackled complex new subjects. That I was starting to see how to really see. When I look back on my early sketchbooks now, I can see that, even after a month or two, I was getting better and better. But at the time, all I could think was: “I will never get there.”

Why? Because instead of comparing me with me, I was comparing me with da Vinci, with my friend the professional illustrator, with all the artists who’d inspired me to want to start to draw. The first bar was way too high. I’d just started to jog and was beating myself up for not running a marathon in under three hours.

It’s essential to recognize that your judgement of your own progress is far from accurate. I guarantee you are doing better than you think you are because again, your perspective is distorted by the dream you have of where you want to get to. And because you feel like an impostor who’s pretending to be an Artist but can’t draw a stick figure. So stop obsessing on on how far you have yet to travel and check out the ground you’ve already covered. Spend less time on self-criticism and more on your next drawing.

How to draw like a natural: Another crucial lesson: don’t skip ahead. Keep working on the basics. Draw simple objects. Draw your lunch. Draw a shoe. Just stick to using a black pen. Don’t plunge into portraiture or three-point perspective or advanced watercoloring. Develop your confidence in the building blocks of drawing: lines, angles, measurements (I explain more in my kourse, How To Draw Without Talent).

And if you can’t quite capture what you’re seeing yet, write down your observations. Draw an arrow to the drawing that explains how the shadow looks, point out the highlight, record what you are learning. Just the act of writing information down, helps your memory retain it. Then look for other examples of what you have observed.

The more actively you engage, the more the lessons become second nature. And that’s really where you want to be, to draw without having to think, to intuitively translate what you see into line son the page. But, like learning to walk, to tie your shoe, to throw a ball, to drive a car, it takes lots of repetition to build the neural connections that make a new skill feel natural.

How to motivate yourself: And of course, if you don’t want to practice, you won’t. It’s crucial to stay motivated, even if you’re not on the verge of a career retrospective at the Guggenheim.

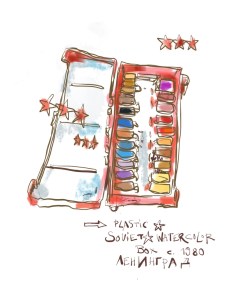

One way is to set yourself small goals that you know you can achieve. For instance, do a drawing every day. Even if it’s just for two minutes, pick up that pen. Or commit to filling an entire sketchbook in the next month. Then celebrate by buying a new art tool. I spent a year drawing with one type of black pen. Then I allowed myself one grey brush marker. A month later, I added a different grey, and slowly worked my way up to a bag full of color markers over a year. The next year, I bought myself a cheap watercolor set. The year after that, a really good watercolor set, and so on.

Try focussing on a single daily subject for a month. Pick a subject you find interesting but don’t try to make an “art statement”. It’s just a theme to practice variations upon. I drew my teacup every single morning. I drew a selfie every day. The view out my kitchen window. Cars on my block. A photo from the front page. Now I draw a dog every day. I get a sense of accomplishment when I see how much I am drawing, not just how “well” I am drawing.

Whenever you complete a sketchbook, spend some time with it. Look back at each page, study what you did, how your work has changed. Get out your phone and make a video as you flip through the pages. Share it online with friends you can trust. Their support and encouragement will help keep you going.

Three facts to write in the inside cover of your sketchbook:

1. Never compare yourself to other artists. Don’t compare your first drawing to their reproduction in a coffee table book. Let their progress inspire but not intimidate you. Compare you to you. That’s all that counts.

2. You’re making more progress than you think. You may not see it but it’s happening with every page. Guaranteed.

3. Everyone struggles at the beginning. Check out early van Gogh drawings. Awful. Struggle is normal, inevitable, a positive sign that you are working things through. Your early drawings are zero indication of what you will achieve in time. Zero.

I hope this helps. Remember, you can do it.

This post was originally written for the Sketchbook Skool Zine. If you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free and full of interesting stuff.

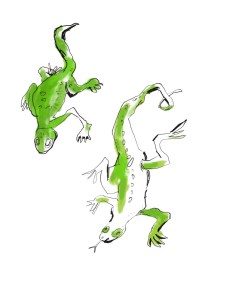

This scary beetle landed on my book. I drew his shape as quickly as I could be before he crawled away, then added textures from memory. I quite like the wood grain.

This scary beetle landed on my book. I drew his shape as quickly as I could be before he crawled away, then added textures from memory. I quite like the wood grain.