Let me tell you a story. It’s about what change sounds like when it’s kicking down your door. And what you do about it when it does.

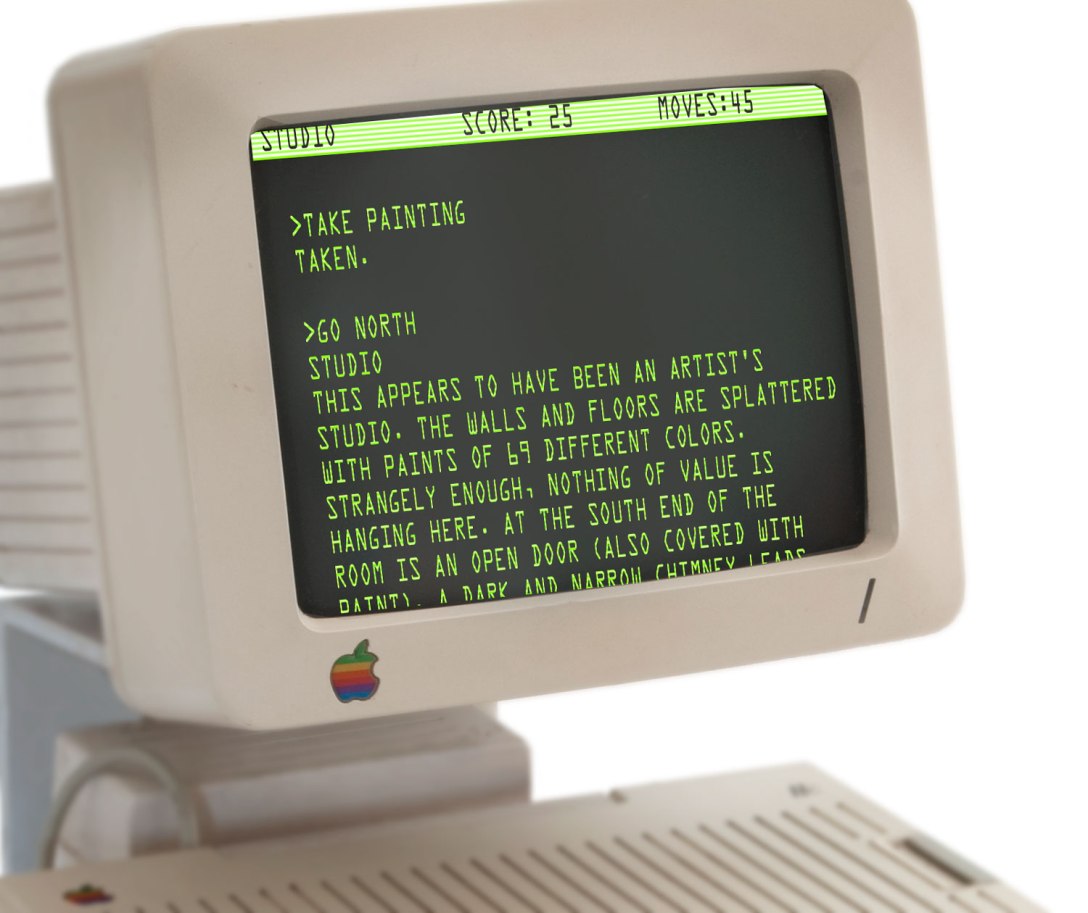

Herman was four years old when his country plunged into the war to end all wars. World War I continued to rage on till he was nine, a boy too small to fight or even understand the causes and implications of the destruction all around him. But he soon felt the fallout.

After losing the military war, Germany was savaged by an economic one. Inflation rocketed to historic levels. It was a terrible time for even a canny entrepreneur, and Hermann’s father was born to lose, even in the best of times. He invested the family’s nest egg, the equivalent of $10,000, in a warehouse full of burlap sacks, then turned around and resold it at what would have been a handsome profit. His buyer was to pay him by day’s end, but stalled. By the time he showed up two days later with the cash, a literal wheelbarrowful, the millions of marks would scarcely buy a loaf of day-old bread. The family was ruined.

Hermann and his siblings were sent door to door through the ghetto, hawking whatever wares their father scrounged together. When his older brother, Josef, rang an unfamiliar doorbell and discovered it was a classmate’s home, he dropped his bag of mantle clocks and ran in humiliation. No amount of beating would get him back out to sell again.

But Hermann persevered, hustling, supporting his family however he could. Knowing no one else would ever come along to bail them out.

In high school, Hermann had shown himself to be exceptional; he was clearly smarter and harder working than any of his classmates. His dream was to go to medical school, then to study with Sigmund Freud and become a psychiatrist. It was a preposterous ambition for an underfed boy from the shtetl but he stubbornly pursued it nonetheless.

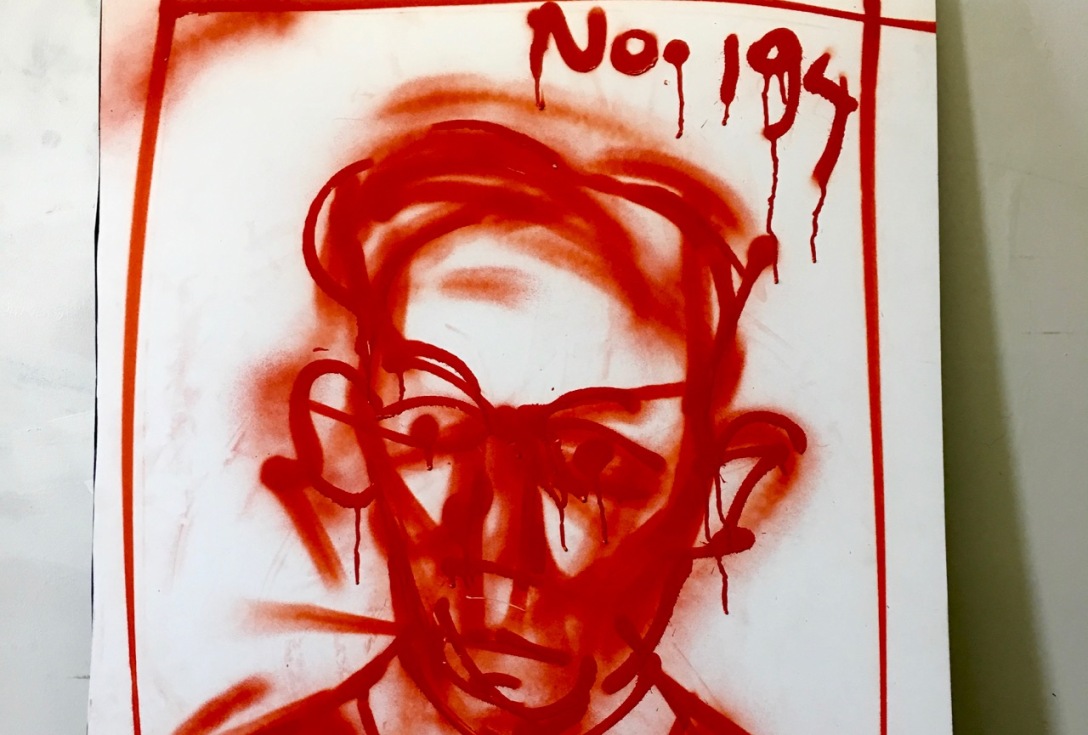

By the time he completed his studies, the Nazis had decreed that a Jew could not practice medicine and he could not be receiving a doctorate. In fact, they announced, Jews should leave Germany all together. Or else.

While the getting was still good, Hermann went to a relocation office to register for exile. In a long line, he meant a lovely young woman from Koln. Kate said that she too planned to be a doctor. He told her he’d heard that Jews were still permitted to study medicine in Rome and that if she was interested, he would remain in line and send her the necessary information and paperwork. She gave him her address, thanked him and left

Not long after, a pair of SS officers stopped Hermann on a train, demanded his papers, and said that he was under arrest. After some deliberation, they told him that red tape meant they could not arrest him on the train, but that he should continue on to his home and turn himself into the local authorities to be arrested there. Hermann got off at the next stop and secreted himself away on the next train to Italy.

In Rome, dead broke, he began studying medicine again. From the beginning. In Italian. He survived on a single herring a day and water from the Trevi fountain. One day, he met Kate again. She had made it to Rome and was still lovely. In 1936, they exchanged cheap gold wedding rings in City Hall, then exchanged them again with the authorities for steel rings enscribed “Oro Alla Patria.” The fascist government mandated that all gold items be turned in to fund the war effort.

Soon after they finished their studies (again) the Italians decided that they didn’t welcome Jews anymore and that they had to all leave the patria, pronto. Hermann and Kate looked for somewhere, anywhere, to flee. Their families had all left Germany for Palestine but Hermann was pretty sure he had a cousin who owed him money and had emigrated to India. So he booked passage on an eastbound ship, assuring Kate that he would find a haven and send for her.

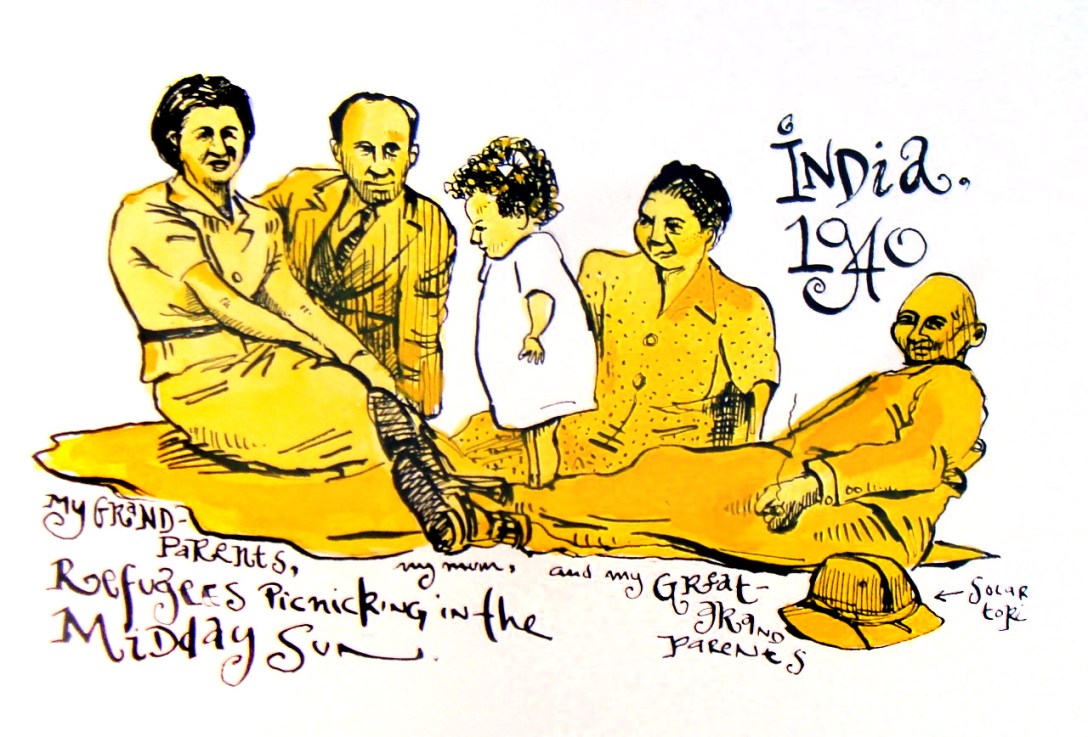

He never did track down his cousin or the money he was owed, but India seemed like a safe place for a pair of young doctors and so he sent for his wife. They set up a practice in Lahore, ministering to British expats, and gave their babies English names. Hazel was born in 1939 and the next year, Michael. A thousand miles from the chaos of the war in Europe, the little family breathed a sigh of relief.

One morning, Hermann opened the door to several armed British soldiers holding manacles. Four pairs, including two for the babies. The family was arrested for being from a hostile county, enemies of the Crown, Germans, and were transported north to a prison camp. There, Hermann and Kate were assigned to be the camp doctors and ordered to treat their fellow prisoners: German spies and Nazi sympathizers. They began frantically writing letters to anyone who might give them asylum, to Palestine, to the USA, anywhere, but to no avail. Even when the war officially ended, they and their children remained behind barbed wire for a total of seven years.

When they were finally released, stateless, with no passports, they returned to Lahore. More upheaval. A civil war between the Hindus and Muslims cracked India in two. Thousands died, millions were dislocated as Lahore became a part of a new Islamic country, Pakistan.

Hermann and Kate and their family stayed on in Lahore. They worked hard, constantly updating their lab and their surgery with the most up to date equipment shipped from the West. They became pillars of the community, treating ministers and film stars. Herman was elected president of the Rotary, then Grandmaster of all Pakistani freemasons. He wore custom suits and owned 40 pairs of hand-made shoes. Kate bought her frocks in London and wore an armful of gold bangles. They had a large medical staff, a butler, cooks, two gardeners. Their chauffeur drove them in a Mercedes-Benz and they sent their children to British boarding school.

In the 1960s, the German government reinstated their citizenship, made an official declaration of apology to them and held a ceremony in their honor in Oberhausen, the hometown Hermann had fled after his encounter with those SS officers so many years before.

Then war broke out on their doorstep again. Their home was just a dozen miles from the Indian border and, as Pakistan and India locked horns and East Pakistan became Bangladesh, Hermann and Kate felt compelled to pack up their belongings once more and depart for Israel. They bought a home in Jerusalem, among their people at last. A year later, on Yom Kippur, they heard air raids sirens and ran down to their shelter. War again.

But this time, they wouldn’t be going anywhere. Kate succumbed to dementia in her 80s and Hermann died in his favorite armchair at 98. They are still in Jerusalem, buried side by side on Mount Olive, waiting for the Messiah’s trumpet to sound.

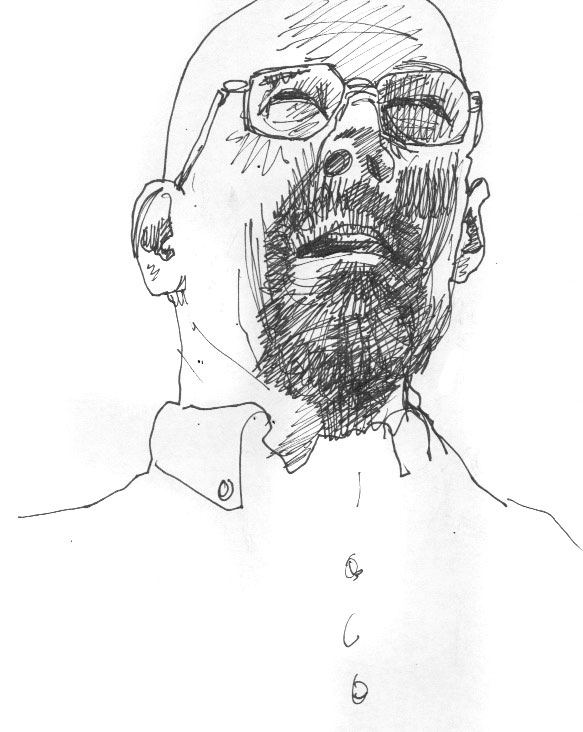

My grandparents’ lives were rife with change, none of it their doing. But every time the deck was reshuffled, they survived and thrived. I never heard them curse their luck or complain about their lot. They weathered all types of persecution, unforeseeable calamities, and yet, they never gave up, always looking for new solutions, new ways to make the most of their changed circumstances.

But it wasn’t easy. I’m sure they must have worried terribly; of course, they did. Hermann became increasingly reactionary as he got older, suspicious of Palestinians, Soviets, liberals, intolerant of anybody who was different. He saw antisemitism all around, and who could blame him after all he’d endured?

Kate’s children ended up living on the other side of the planet, marrying gentiles, pulling away, leaving her feeling isolated. She never practiced medicine after they emigrated to Israel, but became a housewife, she who had been served by a dozen servants. Despite all her years abroad, she enjoyed pottering around in her own kitchen, nostalgic for the days when she was still a fräulein in her happy, tidy, middle-class German home.

When I lie awake at night and worry about all the things that could go wrong – medical, financial, presidential, what have you — I remember all that Hermann and Kate survived, how, even when things were scariest, they pulled through.

They lived through a century of rupturing change — lived and flourished. When I suffer some piddling setback, I think of Hermann sitting down to study medicine all over again, in a language he didn’t speak, a meager herring in his belly, fascists all around. When I worry about madmen planting bombs in dumpsters a few blocks from my home, I think of how my grandparents felt every time tanks rolled past their gates or jets flew overhead. When I get annoyed at the bank or the DMV, I think of how he felt when the SS stopped to paw through his papers. When I feel anxious about my son moving three thousand miles away to start a life in California, I think of how they felt when their families disappeared into the fog of World War II, behind the gates of Auschwitz.

Don’t get me wrong. The fact that many of their trials were greater than mine doesn’t wipe away my worries. And It doesn’t trivialize them either. But it does serve to remind me that I come from hardy, resilient stock. I am descended from survivors. And when you think about it, we all are. Whether we know it or not, the world has gone through far worse than we face today, our new fears notwithstanding. We are free from famine, plague, genocide, and, though the world remains a troubled place, it’s still a beautiful one too. We can decide how we will see things, how we will cope with change, how we will survive. We are free to choose to live each day as if we were going to make it through what ever comes up, firm in the belief that we are going to survive to die in our favorite armchairs, many years from now.