A key to successful learning is to have a motive. Why do I want and need to learn this?

When we first started to learn things, it was to survive in the world. Learning how to walk, how to eat solid food, how to talk, and how to play with others were hard but essential lessons. When we first got to school, we had to learn things because, well, mainly because we were told to do so by adults and because everyone else in the room was doing it too. We didn’t really understand the reason for learning what we are being taught but we did it because it some big person told us too. Eventually, some grown-ups inspired and excited us in the classroom and then we were doing it because it was fun and we wanted them to like us even more. Those kinds of teachers are the ones that have the power to change our lives.

When we are grownups, why do we want to learn things? Generally, because the new skills will help our careers or enable us to accomplish some useful goal like cooking dinner or programming the DVR.

So why do people want to learn to draw? And how do we help them to persevere?

So why do people want to learn to draw? And how do we help them to persevere? People want to learn to draw generally because is a skill that they felt was potential in them for a long time but they were never able to focus on or get proper guidance to fulfill that potential. “I’ve always wanted to draw,” people tell me. But there were huge obstacles that sat in their way — the largeness of the task, the enormous commitment required, and most of all the fear of failure. This stems from the sense that while others may be good at this, you were not born with the talent or ability to ever accomplish even a basic level of drawing ski ll yourself.

ll yourself.

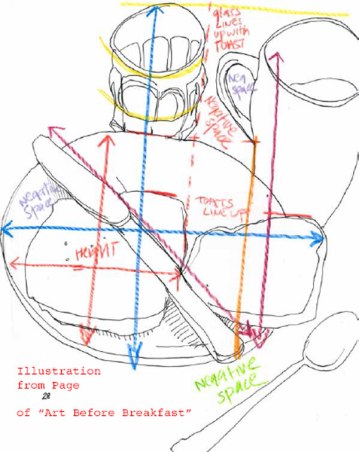

So the first and most important task is to give people back their sense of power. To make them think that they can do it, to show them that that ability does reside within them, and that if they put in a bit of work it will not be wasted effort. Because there is that sense that the process is magical and that, without that spark of magic, no amount of effort or training will pay off.

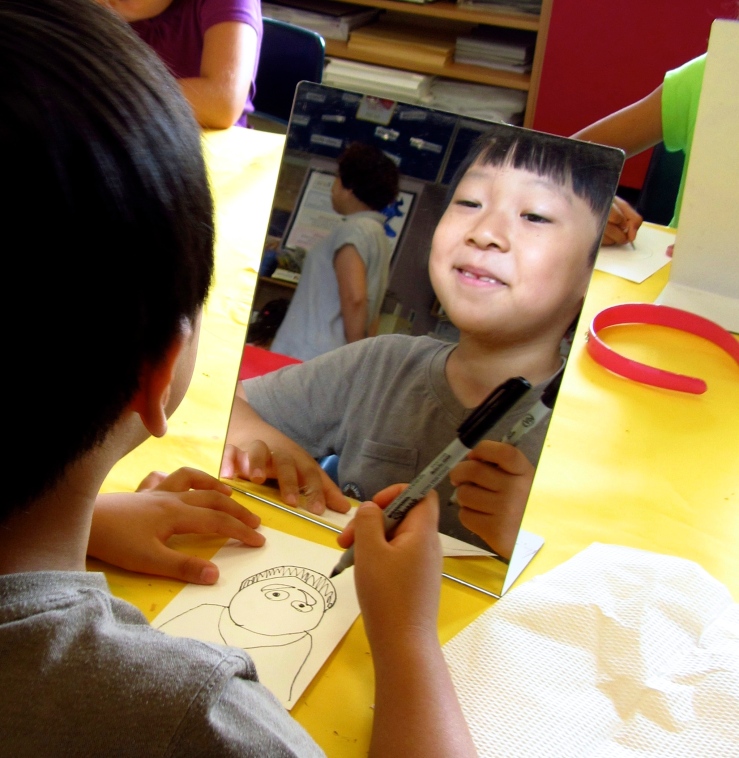

As teachers, we have to show them that it is indeed possible. And the key to doing that is to show them that people just like them —novices, frustrated creatives, people born apparently without talent — are able to make progress in the same way.

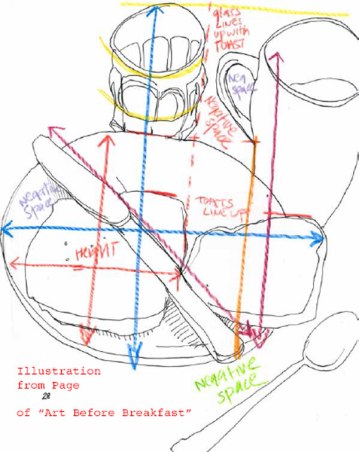

If you look at Betty Edwards’ classic book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, one of the most notable things in it are the ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures. We see accomplished beautiful drawings and next to them the same sort of amateurish fumblings that we are now capable of. The book promises us that, just like these people, we will be able to progress from A to B.

A great way of doing that is by giving people a sense that they are surrounded by like-minded people. Community, is a key part of empowering them. I can tell you over and over why I think you will be able to accomplish this but, unless you trust me, unless you feel I am like you, your inner monkey critic can simply dismiss my expectations and say that I am different from you so my lessons do not apply.

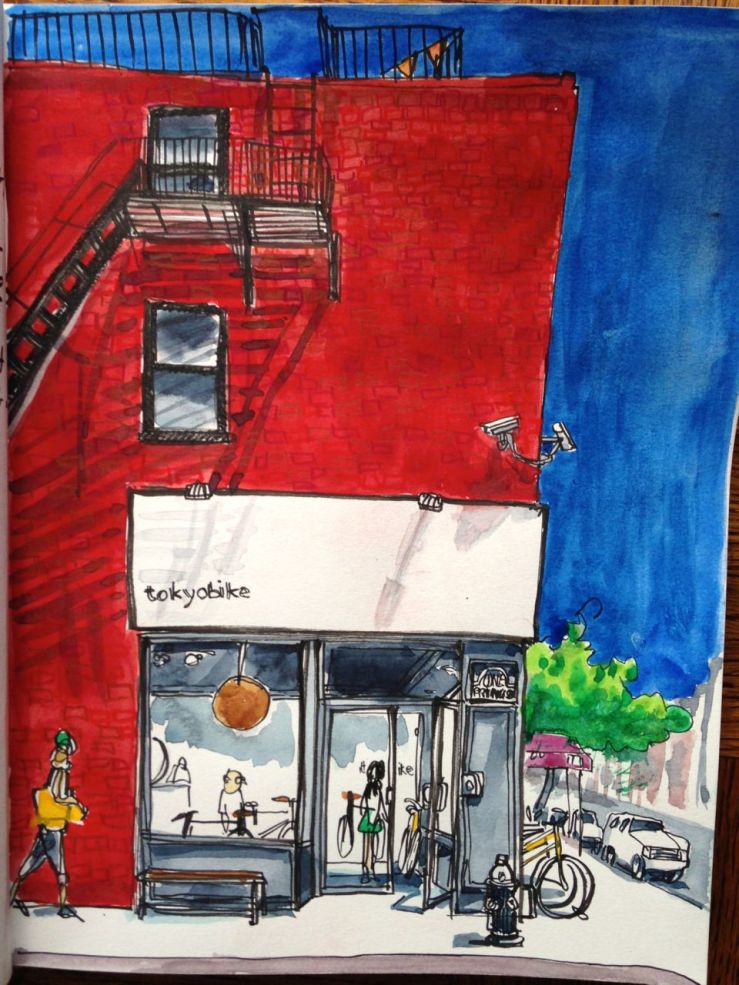

You can buy a book and struggle alone with the exercises, giving up when you hit the first obstacle or disappointing sketch. But when you’re surrounded by thousands of others with the same ambition, the same busy lives, and the same apparently limited talent, you feel like maybe it is possible. And when you have that sense of possibility, the next step is to give you the opportunity to exercise. We need to give you work to do that will be both fun and rewarding. So we need to devise assignments that will fit in with your current life, that will remain interesting and varied, and that will move you one small step at a time, toward the goal of creative empowerment.

When you’re surrounded by thousands of others with the same ambition, the same busy lives, and the same apparently limited talent, you feel like maybe it is possible.

I think it is similar to learn the way we did when we were children, to just enjoy the process, to have fun in the process rather than agonizing over the first meager results. All learning involves work. But it need not feel like work. It should be fun, rewarding, and engrossing in someway.

We have the fantasy that learning a skill is simply a matter of getting access to certain shortcuts. That there is a secret set of tricks that will instantly have us drawing effortlessly and accurately, as if there were secret rules that allowed you to drive a car expertly or shoot a basket expertly. Drawing is a physical skill. Like any other, it takes practice. There are no shortcuts but there are things that will make the effort and time commitment required seem just like fun.

No one of the steps will instantly provide you with extraordinary abilities. But they will build your faith. And that faith means that you will continue to take one small step after another. And fairly quickly you will be able to look back and see how far you’ve come. And that will re-reinforce your faith again so you will continue to work and to move forward.

None of the steps has a magic formula, it just contains inspiration. Because ultimately nobody can teach you to draw — only you can teach yourself. And the way you do it is by believing that you can, and doing the work to develop the skills and the connections in your brain and body to make it so.

ll yourself.

ll yourself.