“Whether he is a sinner I do not know. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see.” — John, 9:25

My grandfather grew up in a small village in Eastern Europe and this was one of his favorite stories:

A peasant comes to the village wise man and he is very upset. “My house is far too small for my family. It’s dark and small and smells of cabbage but I am too poor to afford a bigger one,” he complains.

The wise man strokes his beard for a minute and then says, “Do you have any chickens?”

“Of course I have chickens,” replies the man. “What sort of self-respecting Eastern European peasant do you think I am? I have six chickens and a rooster.”

“Bring them into the house and let them live with you,” says the wise man.

“What? That’s insane…,” the man says. “Chickens in the house?”

“Do it. Then come back in a week and tell me how things are going.” says the wise man and turns back to his book. The peasant leaves, grumbling.

A week passes. The peasant bursts into the wise man’s house. The wise man, not looking up from his book, says, “Well, did it work?’

The peasant explodes: “Of course not. It’s a disaster! There are chicken feathers and chicken droppings everywhere. And the house is even more crowded! We’re miserable.”

“Do you have a goat?” asks the wise man.

“A goat?” fumed the man. “Well, yes, we have a big, smelly goat.”

“Excellent. Bring the goat into the house. See you in a week.”

The peasant leaves, shaking his head with disbelief. He’s back five days later, frantic. “What have you done to me? My life is a nightmare. The goat ate my wife’s best babushka, the chicken have taken over my Barcalounger, and our house smells like a Warsaw subway men’s room.”

“Excellent,” says the wise man. “Your cow — bring her in next.”

“The cow? The COW?! She’s huge! I doubt I can even get her in the front door.”

“Do it.” The wise man dismisses him with a wave of his wrinkled hand and returns to his book. The peasant, his face turning an even more dangerous shade of vermillion, stalks out, cursing under his breath.

When he returns, his hair is dishevelled, his coat is spattered with chicken droppings, a goaty smell emanates from his overcoat, and cow dung’s on his boots. He doesn’t complain, he just stands there, broken, tears cutting a path down his grimy cheeks. The peasant is clearly at his wit’s end. The wise man looks up and smiles. “Very, verrry good,” he says. The man gulps back a sob. A chicken feather drifts out of his beard.

“Now,” says the wise man, “For the most important step. Take all the animals — the chicken, the goat, the cow —and drive them out of your house. Get them all out.” The peasant merely shrugs hopelessly, then turns and shuffles out of the wise man’s house.

The next day, he’s back. He’s transformed. His eyes gleam, he stands tall, his energy has returned. “How is your house then, eh?” asks the wise man, a twinkle in his rheumy eye. The peasant grabs the wise man and kisses his leathery cheeks. “We drove out the chickens, the goat and the cow and now … it’s huge! It’s a mansion! It’s clean and bright and we are so happy. At last! You are a genius!”

Anyway, that’s my grandfather’s sort of story. It came to mind yesterday evening as I sat in the bleachers behind home plate and watched the Brooklyn Cyclones lose abysmally to the Aberdeen Ironbirds. I had one hand cupped over my left eye and a smile as broad as the peasant’s on my face.

Five hours earlier, it being a close and muggy afternoon, I had taken my Kindle and a single dachshund to my bed for a nice Saturday afternoon nap. I’d had a fairly rough night’s sleep, and was a little wracked with self doubt, missing Jenny in LA, and just generally feeling unnecessarily sorry for myself.

I awoke an hour later, groggy and sweaty. I had been sleeping face down and I was especially bleary-eyed. I staggered into the bedroom and splashed on some cold water. I saw a big crease running down my face, from my forehead to my cheek. My vision still seemed bleary so I splashed on some more cold water. I looked out the window and I could not focus on the view. The vision in my right eye was really blurry. I covered my right eye and everything seemed fine but when I did the same with my left, the buildings down West 3rd street would not get sharp. I rubbed it some more. No change.

I waited. Ten minutes. Then half an hour. No real change. Clearly I had done something awful to myself in my sleep. I had been lying on my eyeball and somehow strained it or compressed it or worse. My hypochondriacal monkey had several helpful suggestions. Maybe my vision would never come back? Maybe I would be permanently blind in one eye? Maybe I’d had a stroke?

Jack and I left to catch the F train to Brooklyn to meet my sister, her husband and kids at MCU stadium to watch the Mets minor league franchise play Baltimore.

The ride to Coney Island from the Village is about 45 minutes long and I spent a lot of it in a minor sweat, my bowels liquid with worry. The monkey kept me company. Wouldn’t it be ironic if just as you decided to focus on art full time — you couldn’t focus at all? Maybe you’ll have to wear an eye patch? Maybe you’ll end up with a guide dog? Now you can really do blind contours! Ha, ha!

The train comes above ground once you get to Brooklyn and I kept alternately covering my eyes to peer into the distance. As we reached Avenue X, now an hour and a half after I’d woken up, things maybe, possibly, seemed to be improving. If I just used my right eye, it slowly began to focus on the housing projects in the distance. Then if I uncovered both eyes, it took a minute for them both to adjust. It was wonky but it was changing.

We got off the train on Mermaid Avenue and proceeded immediately to Nathan’s to fortify ourselves with some medicinal hot dogs and fries. I kept testing my vision. The Cyclone, the Ferris wheel, the boardwalk, came into view. I could see details of the half-clad bodies on the beach. Folds of sunburnt flesh, bad tattoos, back hair, varicose veins, details that now looked gorgeous to my worried brain. I realized that the waving blob by the stadium was actually my sister and my nieces. Over the course of the first few innings, I saw the team’s mascot transform form a fuzzy, white shape ( a snow man? An ice cream cone? A thumb?) into a giant-headed seagull, prancing around the diamond.

By the time the Cyclones started to lose badly, I was agog at how beautiful the evening looked. The sky was lavender and fuchsia. The parachute jump was wrapped in a delicate skein of twinkling lights. I could read the signs on the bumper car track, count the bulbs on the scoreboard, see every kernel of popcorn on that large man’s lap near first base. Brooklyn was the most beautiful place on earth and I was, yet again, the luckiest man alive.

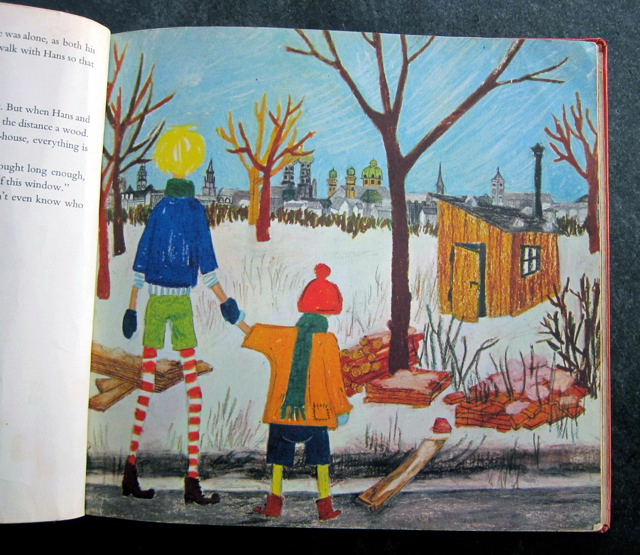

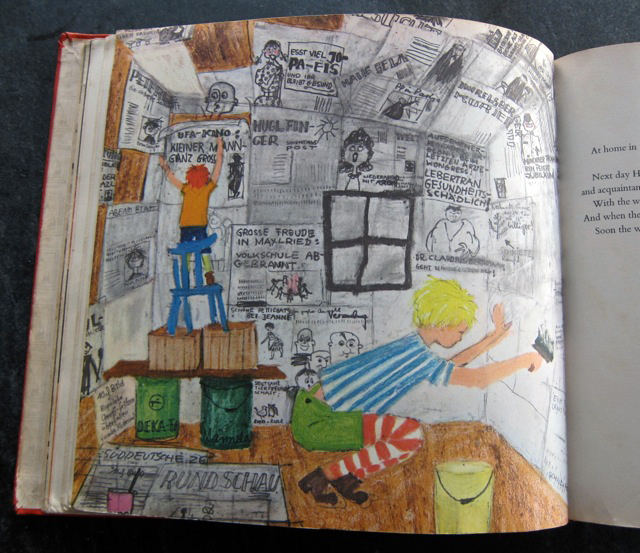

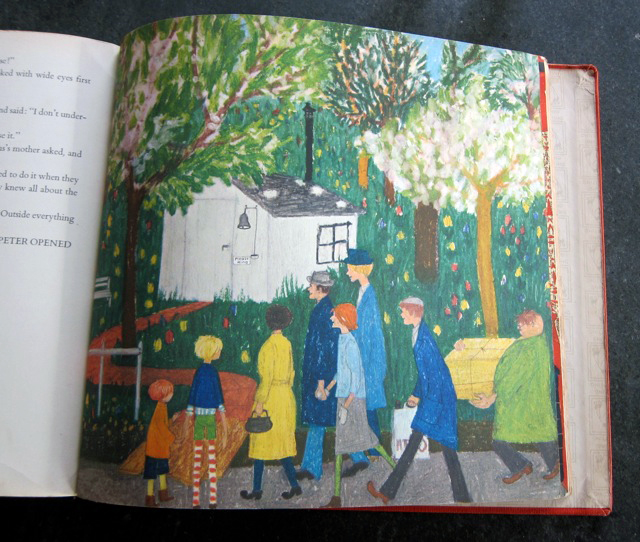

They cover the walls with newspaper and then whitewash it, they install an old wood stove, they plant geraniums in a windowbox, and make gaily colored curtains. The book was Swiss and had bright pastel paintings on every page (they were done by a 15-year-old girl!).

They cover the walls with newspaper and then whitewash it, they install an old wood stove, they plant geraniums in a windowbox, and make gaily colored curtains. The book was Swiss and had bright pastel paintings on every page (they were done by a 15-year-old girl!). I guess it’s the same instinct that had us building forts out of sofa cushions and making a pirate ship out of the linen closet. I yearned for a treehouse or a tent or an empty refrigerator box — something domestic I could call my own.

I guess it’s the same instinct that had us building forts out of sofa cushions and making a pirate ship out of the linen closet. I yearned for a treehouse or a tent or an empty refrigerator box — something domestic I could call my own. Our house has an old two-car garage, built in the 1940s and made of wood with a big swing-up metal door. Since the day we arrived in LA, I have been busily turning it into a studio of my own, a cubby house, a man-cave.

Our house has an old two-car garage, built in the 1940s and made of wood with a big swing-up metal door. Since the day we arrived in LA, I have been busily turning it into a studio of my own, a cubby house, a man-cave. I spent a day on my hands and knees scrubbing the floor, half chipped lino, half cracked cement. Then I built myself shelves, tables, and drawers to hold all my paints, pens, inks, and journals. I installed lighting, a sound system, and a grass green shag rug for the dogs to lie on while I work.

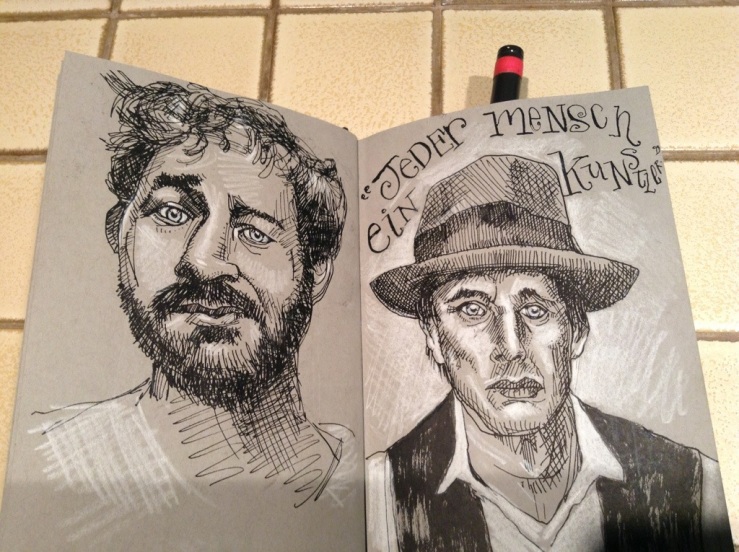

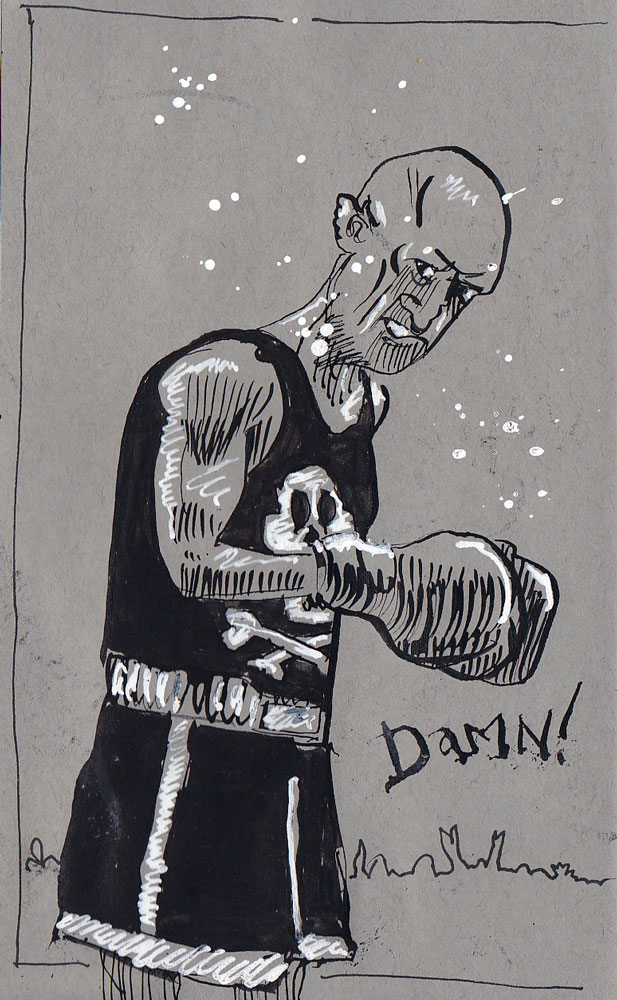

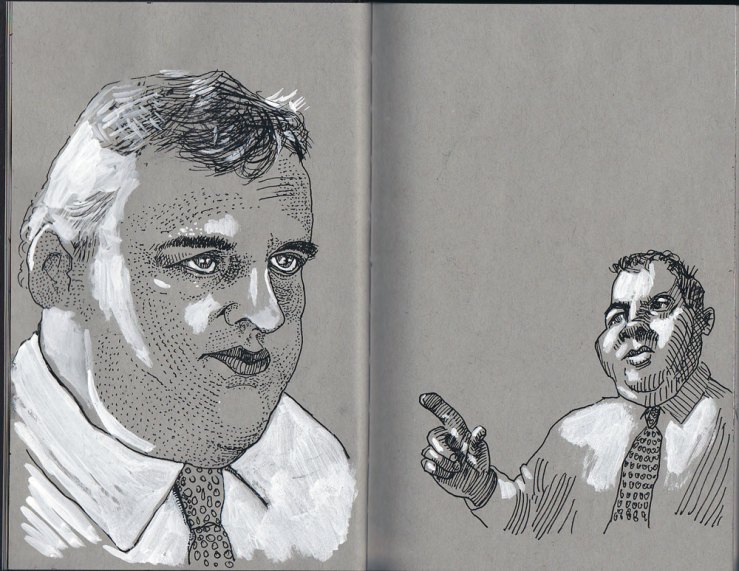

I spent a day on my hands and knees scrubbing the floor, half chipped lino, half cracked cement. Then I built myself shelves, tables, and drawers to hold all my paints, pens, inks, and journals. I installed lighting, a sound system, and a grass green shag rug for the dogs to lie on while I work. Slowly, I am filling the walls up with paintings — the first I have done in ages that are not in a small book.

Slowly, I am filling the walls up with paintings — the first I have done in ages that are not in a small book.