What is the role of feedback in learning? Especially when starting to do creative things, things that are ultimately pretty subjective? When there are no answers in the back of the book?

The biggest obstacle we need to overcome in learning to create is the belief that we can’t. That’s especially true when we learn as adults. We have spent our entire lives believing that we cannot do this thing, and now, unless we are convinced that we can, we will never get to a point of any sort of mastery.

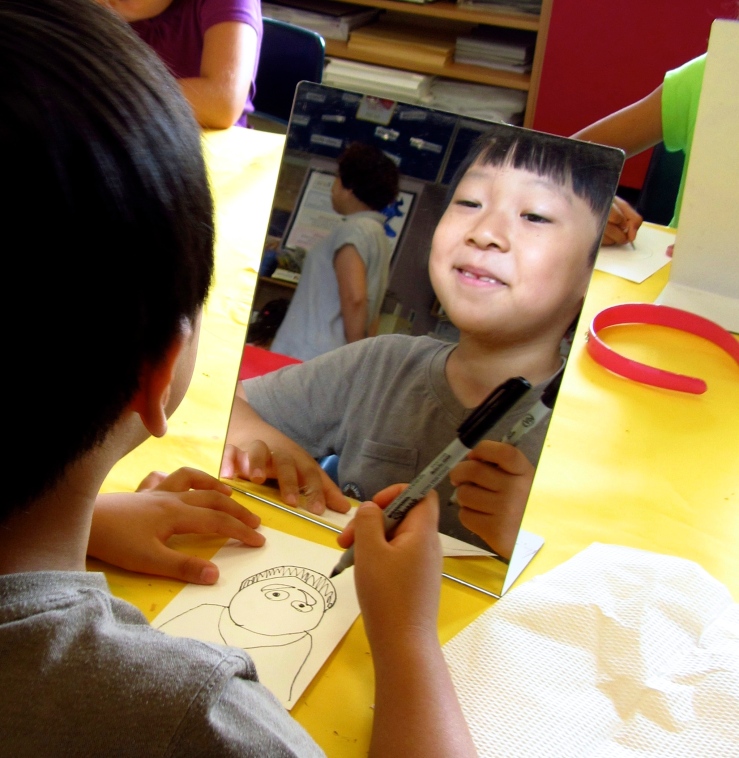

The most difficult and crucial lesson for beginners is the importance of failure. You need to make a lot of mistakes. You need to feel good about those mistakes and recognize that they are opportunities to improve. You can’t allow those errors to overwhelm you and make you feel hopeless.

The biggest obstacle we need to overcome in learning to create is the belief that we can’t.

The reason that people struggle with failure is because they believe that their failures are reflections on who they are as human beings. “Only failures fail.” The fact, of course, is that everybody fails on the path to learning, that failing is the most important part of any education. Researchers have shown that people learn far more from watching others fail than they do from watching extremely accomplished people do things without making any mistakes. You can sit and watch Lebron James shoot baskets perfectly all season but that won’t prove very instructive in developing your own game.

It is much more difficult to look at our own failings as educational opportunities if our egos and self-image are wrapped up in success and failure. When we watch other people fail, we are able to separate failure from ourselves, to see the failure as ‘other’ and thus look at it objectively.That is why it is generally better to learn creative things in a group environment where we can see others struggling and failing. We can see where the mishap occurred or how the problem was not fully solved. The problem exists independently and facing it is an interesting challenge, rather than a demeaning disaster.

…failing is the most important part of any education

What is the value of a teacher’s comments to a new student?

In creative situations, where one’s ego and self-image are tied into the results of an exercise, any sort of perceived criticism can undermine that process. Because we are still so new at learning this new skill, it is difficult to accept that a mistake is not a reflection of who we are and an indication that we shouldn’t even bother tackling this lesson. That’s why we need as much encouragement as possible in the beginning phase of learning, a phase that can actually last for years. We need to develop self-confidence and faith in our own creative abilities and sometimes criticism of any kind can thwart that progress.

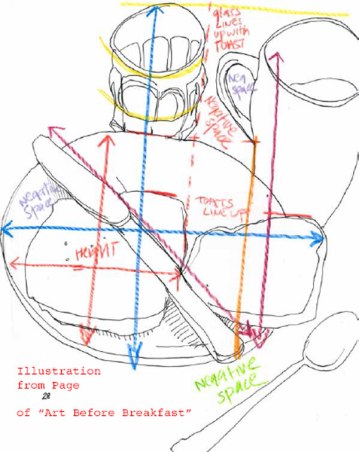

Students often ask for specific advice on how to improve their composition or how to use a certain medium more effectively, and some teachers are quick to provide lots of guidance, rules, and specific direction. I don’t know if that is especially effective. I find that most students are extremely vulnerable to the most benign sort of commentary — even if they asked for it. Simply telling somebody that they might want to consider a different composition, different medium, consider a slightly different approach, can be extremely undermining. There are so many open wounds as one is going through this creative rebirth that everyone involved must tread lightly. That includes the teacher, the student, and the relative looking over the shoulder.

I think it’s more effective to encourage students to experiment, to make more work, and to gradually developed their own answers to these questions. In fact, my experience is that almost all direct input from the teacher (inevitably an authority figure) is not particularly useful before the student has real confidence in their abilities. Instead the teacher should create an environment of trust, inspiration and fun. They should encourage the process, the experimentation and exploration, provide reassurance and safety, and do demonstrations in which they explain their own process, rather than making specific suggestions about the work the student has done. Turn the key, but don’t grab the wheel.

Turn the key, but don’t grab the wheel.

Many novice students believe that there are shortcuts available that once revealed will turn the student from an amateur into an expert. They want to know what brand of pen the teacher uses under the misimpression that the pen is the secret. The fact is that the student will do much better by discovering answers on their own, by studying the works of others, and by trial and error. There isn’t an accumulated body of knowledge that the student can acquire which will transform them. That knowledge only comes through years of work.

But that doesn’t mean the student can’t be delighted with their accomplishments almost immediately. Especially in the beginning of a creative education, progress happens quite quickly, simply by feeling empowered and free to actually make things. Sometimes that simple realization can wipe out years of anxiety around creative issues. And with that freedom comes an opportunity to continue working and develop one’s own style and techniques.

But that doesn’t mean the student can’t be delighted with their accomplishments almost immediately.

Personally I find that students with the most technical skills alone rarely make art that I find very interesting. Instead I’m far more excited by people who make mistakes and discover new and interesting ways to overcome them.

Learning the tried-and-true ways of making art is not necessarily the way to make great art. It is simply the way to rehash the lessons we’ve already learned, to make more art that is ready familiar. Instead you want to create new and exciting directions, to take risks, to see the world afresh, to find answers to new questions. Learning to draw is not like cooking Boeuf Bourguignon, a set of steps one can follow from raw ingredients to final delicious product. Instead it is a voyage, an excursion into the wilderness, an adventure that is mainly rewarding for its own sake, not for its results.

The teacher doesn’t have the answers. Only the student does.

ll yourself.

ll yourself.