Category: Art

Examples, instruction, advice, recommendations, and more.

Painting No. 1

Patti and the monkey

Tim sent me the following email last week:

Hi Danny,

Thanks for Shut Your Monkey. I’ve been working on quieting my inner voice for 40 years mostly through meditation. I’ve added Shut Your Monkey to the list of books that have helped me over the years including Be Here Now, Ram Dass; The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle; Experience of Insight, Joseph Goldstein; The Art of Living, William Hart; and Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Sogyal Rinpoche.

Where your book has been extremely helpful is in discovering those nooks and crannies where my Monkey has been hiding and impersonating my voice with subtle little comments that I didn’t recognize as coming from him. So thank you.

I do have a question for you. I’ve been following you for a number of years and was especially touched by your willingness to be so open about your wife’s illness and death. I’m wondering how that inner voice was part of that experience?

Tim

Here’s what I wrote in response:

Tim:

I’m so glad my new book is helpful. Thanks for letting me know. I am flattered to be in such august company.

As to the inner voice and my wife….

When Patti was first injured, we spent a lot of time looking for information. We were in a fairly narrow niche among people dealing with spinal cord injuries: 1) my wife was a woman (obviously), 2) we had a 9 month-old-child and 3) we lived in a big city and 4) she was over 30. There just weren’t many people like her (one more way Patti was special). We were in a constant quest for information about our particular situation and it was hard to come by in those early days of the Internet. So I started a bulletin board called curbcut.com and it soon became a vibrant community for sharing information and support. You can see part of an archive of it here. The discussion we had there had to be frank to be useful and it became increasingly normal and comfortable for us to tell total strangers some pretty intimate stuff in order to get useful feedback.

Similarly, when I started drawing, there was very little information and inspiration about illustrated journaling. Hannah Hinchman had a book, d.price had a zine, but otherwise not much. So I formed a community on Yahoo! that quickly grew to 4,000 members.

In both cases, I found that sharing what I was going through with other people helped me and help them. That’s why I wrote Everyday Matters and eventually A Kiss Before You Go and Shut Your Monkey too. And that’s why I have been blogging for all the years: because turning the things of my life into words and pictures helps me understand them better and sharing them with people, even strangers, makes even the worst moments seems worthwhile.

The monkey doesn’t always agree. He told me many time that my sharing was actually exploitation, that I was turning my family into fodder for my bottomless need for attention. That may be true. But so is my other point: when I turn my experiences into some sort of art, it makes my life richer and clearer to me. And when I make art, it seems natural to share it. That’s what artists and writers do.

Sharing stuff publicly hasn’t had many negative consequences beyond the whining of the monkey in my head. And it seems to help other people too.They write to tell me that I am not alone in my feelings or that my description of an experience has helped clarify it for them too.

The monkey has a lot to say about every one of my projects. He has been particularly vocal about my book/podcast/newsletter. Nonetheless, creating them has been helpful to me and hopefully to others too so I persevere over the cries of outrage in my head.

I hope that’s helpful. Thanks for asking,

Danny

New Podcast: Jonathan Carroll

Every artist has their own way of working — tools and techniques they’ve honed over years of practice. We each figure out what works for us, what we need to do to pull an idea out of the recesses of our minds. Every artist faces obstacles and self-criticism along the way and being productive means figuring out ways to dodge the arrows the monkey fires at us as we settle down to work.

Some people start work at the crack of the dawn, while the monkey is still groggy and unable to put up a fight. Others work late at night when the monkey is exhausted. Some have stringent rules for how they work, what pens, what software, how cool the room, how hot the coffee. Some plunge into work like lemmings off a cliff; others fret and bustle about, sharpening pencils and brushing lint off their smoking jackets.

It’s fascinating to learn about the processes we each devise, but there’s no one correct way to proceed. Each person’s monkey erects a different set of road blocks and each of us has to figure out our own way to navigate around them.

One of the cool things I’m discovering about making this podcast is that it’s a great excuse for meeting people I admire and asking them all sorts of questions about their private doings. I happen to discover that one of my favorite novelists, Jonathan Carroll was following me on Twitter so I tripped all over myself to invite him to join me at the microphone.

What a treat! We talked about how he starts a novel, why writers need to read, how the wrong day job can leech your soul, what it was like to grow up in an intensely creative family (his dad was a screenwriter who wrote The Hustler (what a flick!), his mom was a star on Broadway, his half-brother is the genius composer Steven Reich), what it’s like to read your own books, how to judge an artist’s work, how to become friends with your inner creator, and the joys of writing books by hand.

Here’s the episode:

Or better yet, subscribe to the whole series on iTunes (and leave a nice review).

Or you can visit monkeypodcast.com and listen to the episodes right in your browser.

What’s your experience with your monkey? How has it affected you, and how have you overcome it? Record your Monkey Tale at dannygregory.com/monkey.

Jonathan also pointed me to this great video of Francis Ford Coppola showing the manuscript for The Godfather:

I’m pretty proud of this.

My friend Michael Saia, one of the top film editors in New York spend a couple of weeks taking all of the hundreds of little documentaries we’ve made and turned it into one short film that tells the story of Sketchbook Skool.

It’s been two and a half years in the making and stars tens of thousands of people. It’s emotional, it’s funny, it’s exciting and it’s real. Dozens of students made videos telling their feelings about the Skool and I am so moved by their passion for what we have done. I never imagined that this project would grow so big or touch so many lives but it’s wonderful to see how it has.

If you like this film, please consider joining us for the next term at sketchbookskool.com. It starts on June 10. And if you are already enrolled, please share this film on social media and with your friends. I really appreciate your support.

New Podcast: My monkey made me write this.

I had big plans for this week, clearing the decks so I could focus on doing some writing and drawing. Instead the monkey managed to help me find a million distractions.

He and I have been having a lot of discussion about why I need to force myself each week to A) make a podcast, B) make a newsletter and C) write a blog post about it as well. He insists that I need to be consistent about it or else I will disappoint my dozens of fans. I would rather be a bit flexible and play it as it comes but, as you can see (because you are reading this), he won.

To be honest, we could totally switch places. I could say it’s important to commit to this and see where it leads me and he would say, take it easy, it’s 80 degrees out, let’s go eat a Good Humor bar in the park. He loves moving the

I think he’s worried that with a fat block of free time, I might come up with something really nuts to do next.

In this week’s podcast, I talk with Todd Colby, the poet, artist, and former member of Drunken Boat. We’ll discuss the creative process and the role of discipline and preparation in keeping the monkey at bay. Todd is awesome, so’s his poetry and his art and his band rocked savagely hard.

Monkey of the Week: the Paranoid. It’s that voice that says: “They’re laughing and sneering, because no one likes you. Or trusts you. Or admires you. And they can’t wait to see you screw up.” What can we say in response?

Monkey Tale: Lenore has a revelation in the shower about who her monkey really is.

All the episodes of the Shut Your Monkey Podcast are on iTunes.

To hear them, you can can either:

- Subscribe directly from your podcast app by searching for ‘Shut Your Monkey’.

- Or you can click this link and it will take you to the iTunes page.

- Or you can visit monkeypodcast.com and listen to the episodes right in your browser.

-

Do you have a meddling monkey?

Tell me about it. I am collecting Monkey Tales, stories from all sorts of people about about the challenges the monkey brought them and how they dealt with them. Real stories, real moving. If you have a monkey tale you’d like to share, just visit my website and click the red tab on the right to record it. That would be great.

Drawing without drawing.

A couple of days ago, I had a mindful moment in an unlikely place. I had to go to a government office to renew a document. It was a large room filled with rows of chairs facing a series of steel desks with computers and clerks. Not Kafkaesque, just dead boring. I wasn’t perfectly prepared for this chore — it was one of a series of appointments I had that day and I had rushed there from a completely unrelated matter.

As a result, all I had with me was a sheaf of important documents. In my hurry, I hadn’t brought anything to while away the time, no book, no sketchbook. But the Kindle app on my phone was stocked with several books if need be. I figured I’d be fine.

After much paper shuffling and stapling, the desk clerk handed me a number and pointed at the sign on the wall: “No phones, cameras or recording devices.” If I took out my phone, she said, I’d be booted and have to make a new appointment for another time.

I shuffled over to an empty seat and slumped down, feeling like a snot-nosed, scuffed-kneed nine-year-old waiting to see the principal. Rows of people surrounded me, their faces blank, their eyes glazed. On the wall, a counter displayed a four-digit number in red letters. A number significantly lower than the one on the chit in my hand. I’d be there for a while.

I spent a few minutes grumbling to myself about the archaic ban on mobile devices. What could be the stupid reason? I’d already had to empty my pockets and pass through a metal detector to get into the room. What did they think I’d do with a phone? Snap pictures of my co-victims? Of the lovely clerks? Of the tottering piles of yellowing papers? Of the warning signs, the 20th century computers, the flickering fluorescents? Grumble, groan.

I fidgeted a bit in my uncomfortable chair, then I squirmed, then I examined at the boil on the neck of the man in the seat ahead of me, then tried to calculate if the glowing number on the counter was prime. I hadn’t had lunch yet so I spent a while listening to my stomach too.

Then I noticed a spray bottle of glass cleaner on one of the metal tables. I thought, that’d actually be interesting to draw. I had a pen in my pocket to fill out forms but no sketchbook. Then I remembered the neatly paper-clipped stack of papers in my lap. I flashed forward to handing over these documents to an official, papers now covered with drawings of Windex bottles and neck boils. No, I wants things to go smoothly and handing in my VIPapers festooned with junior high marginalia wouldn’t cut it.

I went back to looking at the bottle. I liked the way the neck curved into the body, the six concentric rings that were debossed into the plastic, the soft highlight in the middle, the way one square side of the nozzle was a slightly darker red that the next.

I decided to draw the bottle with my eyes. I coursed slowly along the edge, looking deeply just as I would if I were drawing. I made a run around the edge of the label, a contoured path with one continuous line. Then I jumped to the edge of the blue trigger, cruising into the hollows that fell into shadow, peering in to see every detail I could pull out. I trekked up the side, then slowed myself, not wanting to hurry too fast even though it was an unpunctuated stretch. Move too quickly, I told myself, and you miss something. I down shifted, making myself maintain the same pace no matter how dull the landscape.

A chair squeaked. I looked up, ten numbers had flipped on the counter. Still a way to go.

I moved to the boilscape on the pale neck in front of me. I uncapped my mental pen again and started to draw each hair surrounding it, the rivulets of sweat, the fold of flesh, the soft ridge of fat. I worked my way down to the yellowing neck of the t-shirt, then across to the right shoulder, then down to the sleeve, the arm, the top of the next chair, up the leather jacket of the man in the next chair, documenting each fold in the leather, then up the neck tattoo, across the lightly freckled shaven head, then up a column, over each poster, on the bulletin board, down the clerk’s handbag, over her bottle of Jergens, around the stapler and then a loud cough brought me back. My number was up. Forty-five minutes of my life had been compressed. I gathered my papers and approached the clerk on a cloud.

This morning, I sat in my kitchen. It was six thirty and the sun washed the room. I had been asleep five minutes before but I decided not to start this day by reading the paper and scanning my email.

Instead, I went back to my moment in the temple of bureaucracy. I’d felt surprising peace there on my stiff-backed chair and it seemed it be a nice way to start my day, a little contemplation of nothing. I fixed my gaze on the top of my range, the burners and the bars that criss-cross the top, and started to trace the edges of the first one with my mind. The bars are black, so are the burner and the steel pan underneath, but the morning light made a hundred gradations of the curves and angles. The vertical bars stretch away from me, perspective forcing them into lozenge shapes The angled bars were cut by the bars in front of them so they formed jig saw shapes. I looked at each one in succession, working my way towards the back, increment by increment. The kitchen clock ticked away.

After twenty minutes, I had traversed the whole left side of the stove top. I slid my sketchbook over, uncapped my pen and spent the next twenty minutes taking the same trip, only this time I recorded the observations I made. At 7:20, Jenny came in to make coffee and the spell was broken.

I’ve never thought of myself as capable of mediation, but I think this exercise has a similar effect, slowing down and clearing my mind before the day begins and giving me a boost of creative energy that had me writing this blog post and sipping my morning tea.

I liked it. I think I’ll call it Omm-bama care.

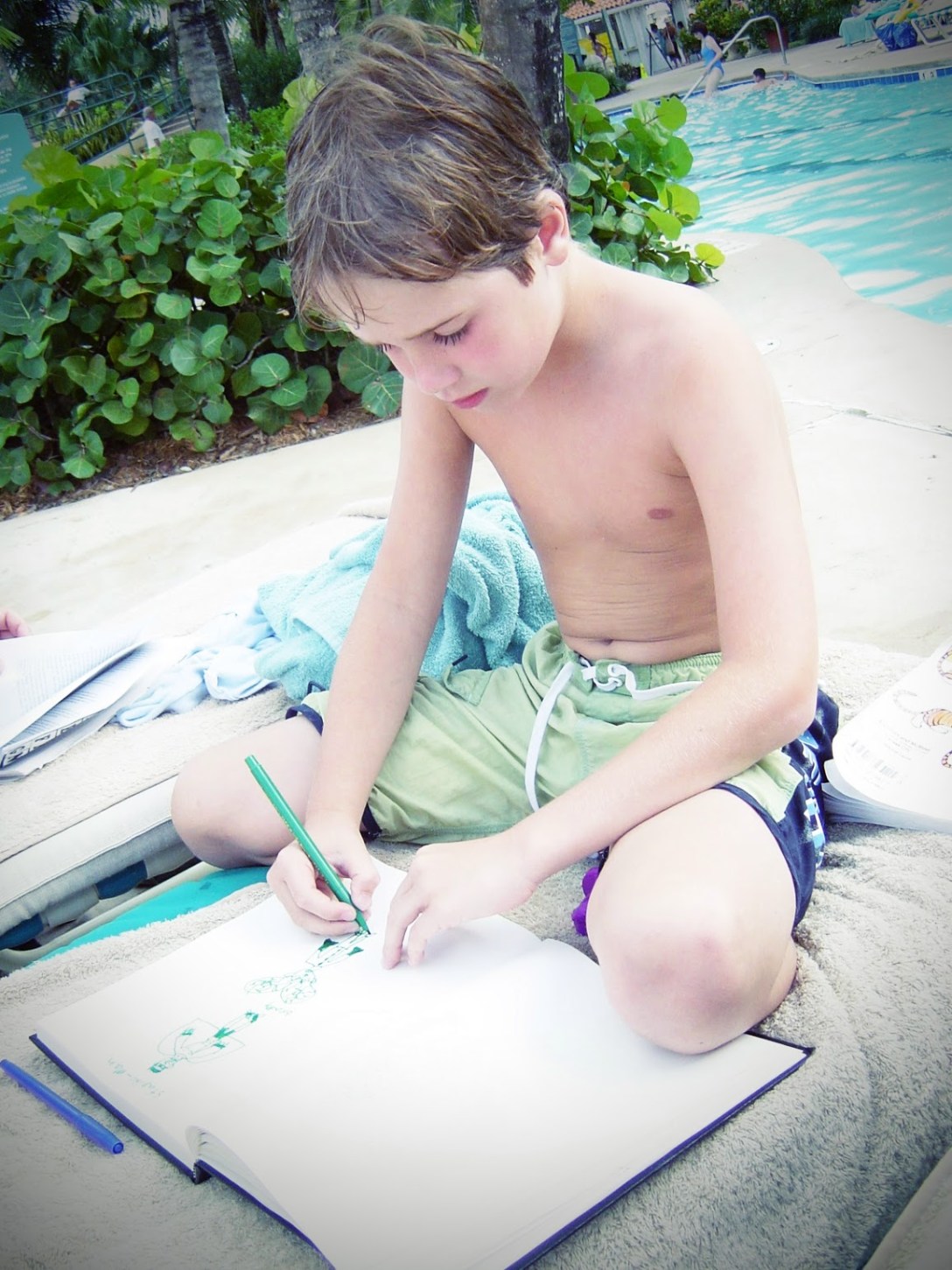

The artist I love most.

When Jack was little, we started collecting his drawings in books labelled the Collected Works of Jack Tea Gregory. Before he was in middle school, we’d filled a shelf with big fat volumes. I don’t know that we always thought he’d be an artist— we didn’t give much thought to what he’d be like as a grownup. But he liked to draw and he had a great imagination and he made a lot of stuff all the time and that was just the way Jack was.

After four years at the Rhode Island School of Design, Jack and five other painters had their final Senior show last night. People held glasses of ginger ale and milled around walls covered with paintings and videos and projections. Jack had three pieces in the show, a sculpture, a painting and teeny, tiny drawing and layer he lead us up to his studio to see the rest of the work he’s been doing since he came from Rome last Christmas. It was voluminous.

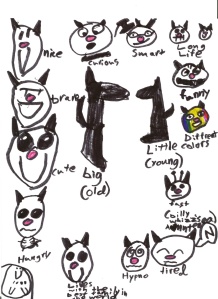

Jack has been working on a series of related works for the last few months, all inspired by an encyclopedia of dogs he had as a kid. There’re a half dozen large, monochromatic and semi-abstract paintings based loosely on dog photos. There is a series of drawings and sculptures about Pluto and Goofy. A fabric sculpture of Pluto wearing dog mask that was embroidered with images of Goofy. A paper sculpture of an articulated dog that ran when you turn a crank. There was a huge painting of an attacking German shepherd. An abstracted figure with a speech balloon and a blurred action stroke. A book with a soft embroidered fabric cover that was filled with stretched digital abstraction and debossed imprints of dogs.

He has been working on a long series on Instagram. Each day he’d make a crude, bulbous, clay sculpture of Mickey Mouse. The next day he’d destroy the sculpture and reform it into another Mickey and upload a new picture. It went on for months.

Jack’s work never offers easy answers. It’s not ironic even when it’s using pop iconography. It’s always filled with emotion and a certain lack of control. It evokes loss and a commemoration of the underdog. His subjects always feel abandoned and overlooked.

When he was 19, he made a series of little sculptures he set up in the lost corners of alleyways around town. They were made by a fictional homeless artist who worked with found materials and then abandoned the sculptures to be ignored by passers by. The final pieces themselves were photos of the sculptures and their environs. One was in the ATM vestibule of a bank, photographed by a surveillance camera. In Rome, he made an installation of grubby, scratched and bent photos in glass frames. One had fallen to the ground and lay smashed underfoot.

Jack is an upbeat, funny guy. He has lots of friends, is warm and open. But his work reveals a dark part inside of him, forged perhaps by Patti’s disability and death, by his concern for the underprivileged and exploited.

Jack has always been a defender of the downtrodden. In middle school he was preoccupied with slavery and wrote plays and made drawings about old slaves who had lost their power to work. He has always worried about racism and sexism and how animals are treated.

I am so proud of him.

His willingness to reveal his feelings in his art, to have such high and selfless values, to be committed to his own creativity — they all make me bewildered at my part in making him who he is.

I don’t know where his art is going. Or where his life is going. It is beyond my control, even my influence. I think it will be challenging at times, the life of an artist always is. But I know it will be rich with experience, discovery, emotion, beauty and truth.

It’s hard for a parent to let go. To admit that your child is doing things you can’t do, sometimes can’t understand. But I have enormous faith in Jack and his abilities and talent and mind. I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Swimming with Lisa Congdon, Pt. 3

In the final lap of our chat inspired by Lisa’s new book, The Joy of Swimming, Lisa and I discuss why men and women are different when it comes to learning, how to be creative without making a living at it, and the challenges of being an authority.

Swimming with Lisa Congdon, Part 2.

More of my chat with illustrator and author, Lisa Congdon and Lisa’s new book, The Joy of Swimming. In this installment, we talk about swimming, art, and what it means to begin art-making as an adult.