In New York, they say, you are never more than ten feet from another human being. If there isn’t someone next to you or behind you, then they are on the floor directly below or clomping around on the floor above. Even if you wander deep into Central Park, lost in a fantasy of woodsmanning deep in a copse surrounded it would seem only by squirrels and woodpeckers, a bunch of Italians or Koreans will inevitably blunder around the corner clutching guidebooks and ruining the calm with their foreign tongues.

No wonder we New Yorkers are so misanthropic; we can’t get away from people.

It wasn’t always so unusual to have some space to oneself. When I was an odd teenager, I used to go alone to the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens of a Sunday. In the ’70’s, most of Brooklyn was still uncool, and I could stroll my grounds for ten or fifteen minutes without seeing a single other (non-imaginary) person.

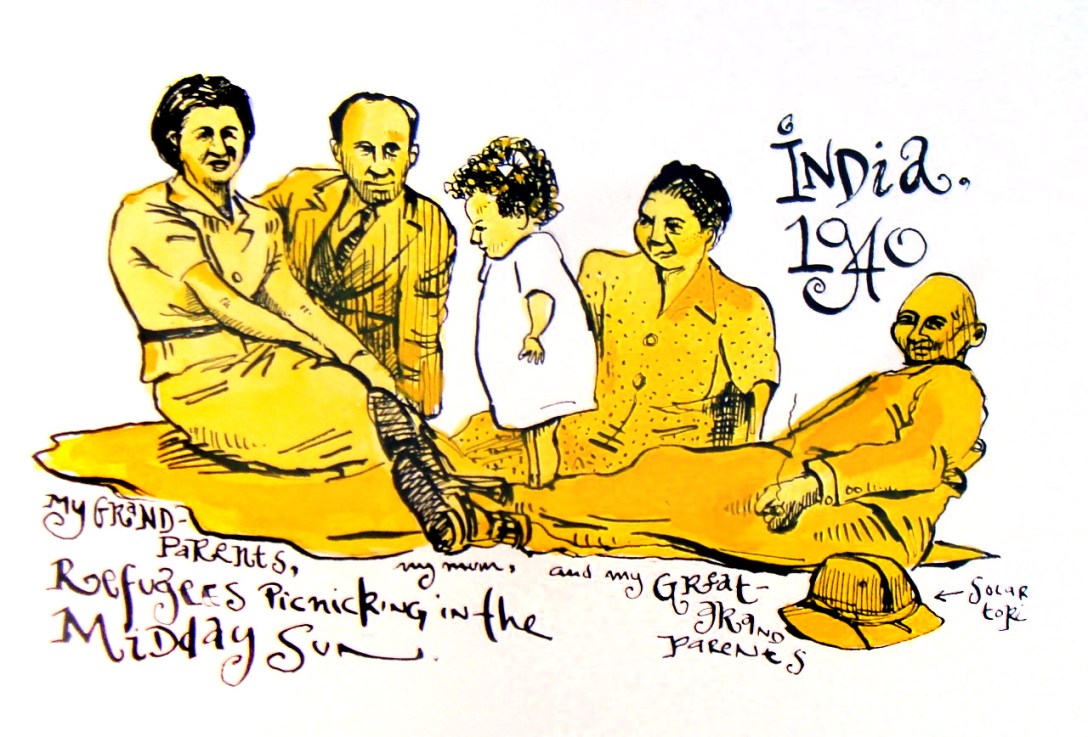

Those were the days when I read all 92 volumes of PG Wodehouse as well as Anthony Powell, R.F. Delderfield, Evelyn Waugh, and other perpetuators of the mythical British landed gentry. While my classmates were making zipguns and apple bongs, I was sewing suede patches on to the elbows of my thrift store tweed jackets and shopping for monocles.

My only companion to the Gardens was my imaginary friend, Lord Roger Watford, and we would walk through the rose garden, pretending that it was part of my vast baronial estate and that the adjacent Brooklyn Museum was in fact my manor House.

Brooklyn has changed a lot since then and so, by and large, have I. But one of the many delights of the studio Jack and I rented this summer was having access to the vacant lots, abandoned dumpsters, and empty streets of the 100+ acres of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Yard was once abuzz with shipbuilders preparing to conquer Japan but in the ensuing decades it became an abandoned stretch of dandelion farm along the East River. Recently it has been landmarked and revitalized and turned into a hive of artisanal activity, full of little manufacturers and artists and photographers and woodshops and film studios and even a commercial farm.

We rented a studio from two women who had been painting there for several years and were taking the summer off. It’s several hundred square feet on the third floor of a brick building, neighbored by a landscape painter, a potter, and two graphic designers. The building is all industrial utility, with painted cement floors, steel casement windows, wide staircases, no air conditioning, and a tarpaper roof that looks out at a spectacular views of the East Side of Manhattan, stretching from the Brooklyn to the Manhattan Bridges and beyond to Queens and the Bronx.

There’s a street full of crumbling rowhouses being demolished on one edge of the Yard, and wandering through the site reminds of the exhilarating freedom I felt when I was ten or eleven in Israel, sneaking into building sites to inhale the smell of fresh cement to look for abandoned porn magazines, cigarette butts, and the dregs of dusty beer bottles.

On the ground floor of our building was a photo production studio full of industrial printers that churned out materials for store windows and fashion shows. There dumpster was filled to the brim with sheets of rejected foamcore, aluminum plates, and rolls of paper and fabric. Other dumpsters in the Yard brimmed with cardboard boxes, wooden pallets, skeins of wire, plastic buckets, and dead computers and TVs.

These dumpsters became my art supply store. Each time I biked into the Yard, I would dive into one dumpster or another and pull out some interesting surface to paint on. Yards of rubber matting, an old canvas, a sheet of plaques honoring David Dinkins to be displayed at the US Open, an life-sized portrait of a blank-faced Calvin Klein model.

I’d haul my find up the three sets of stairs to the studio, turn on the fan, flick on the radio to an eclectic college station in New Jersey, fill my water jug in the janitor’ sink, and get to work.

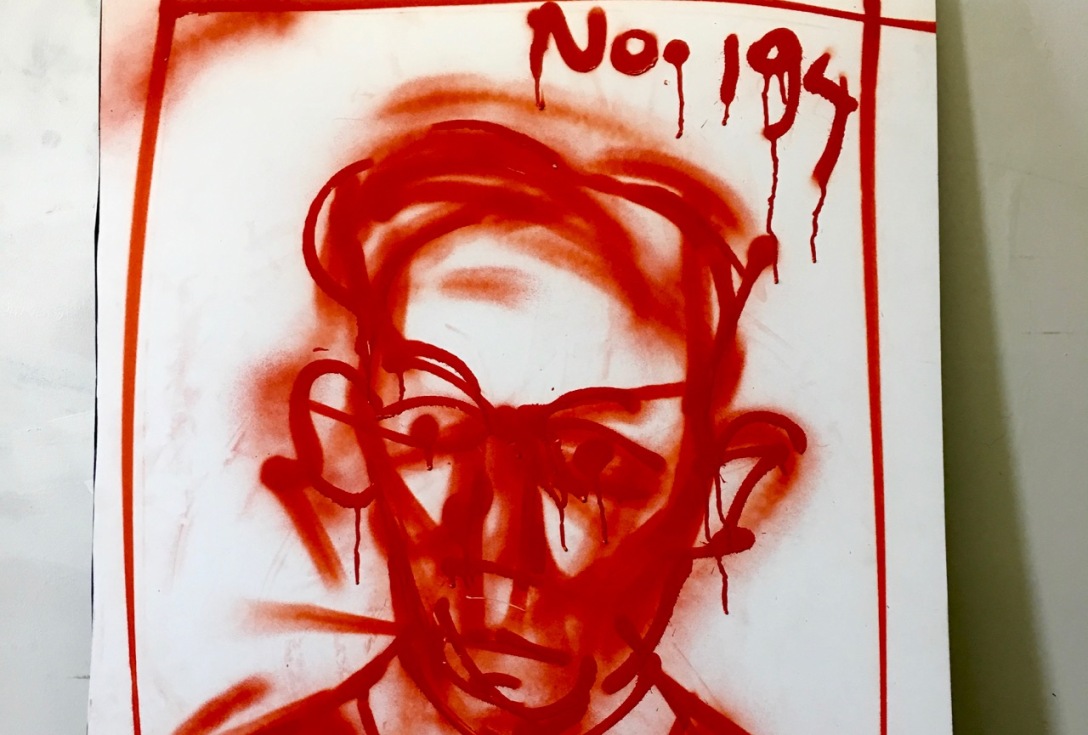

I came with nothing. No ideas, no ambitions, maybe just a small plastic bag from Blick containing some medium I’d always wanted to try. At first, it was spray paint. A dude with too many eyebrow rings explained what the variables were that led to an entire wall of locked cages of paint. Gloss, high gloss, flat, matte, indoor, enamel, oil, acrylic, high pressure and low, and every color known to man. We flipped through a menu book full of spray caps and nozzles and I assembled a bag of twelve, different shapes and angles of spray, some slim as a pencil, others designed to cover a wall and empty a can in seconds.

I hauled a placard announcing a diabetes fundraiser up to the roof and uncapped a can of matte black acrylic. I snapped on a medium-sized nozz and made a slow oval on the board. It was a lot less controllable than I thought. I built up faint layers to sketch out a head. Then I discovered that if the faster I moved, the sharper the stroke. I used my whole body to make the stroke, reaching up then bending down to the ground. Slowly, like layering sfumatos of watercolor, a face emerged. It wasn’t a face I’d imagined — it just appeared through the gloom.

The paint dried almost immediately in the baking July sun. I dragged the board and the cans down to the studio and squirted out a few inches of white and of black acrylic onto a folded sheet of paper. No palette for me. Jack had already explained that he and his pals at RISD didn’t go for all that jazz, no sheets of glass or wooden ovals with thumb holes. Just throw some paint down on the table and have at it.

Now, I used to fool around with acrylic paint back in high school (after I returned from surveying my property and mixing with the commoners), but I have been a watercolorman for the better part of a decade. Painting with opaque paint is so very different from watercolor. I like to layer my paint and build up glazes, slowly shaping the image over time.

But opaque paint like acrylic, oil, and gouache obscure whatever’s beneath them. You are committed to your last stroke, rather than conversing and harmonizing with all the layers before. This took some getting used to. Unwieldy as the spray paint is, it allows for that process of building. With out a medium of some kind, the acrylic just negates all that came before.

I had also forgotten how much of large-scale painting requires you to move around. Unlike working in my sketchbook, a painting that’s four or five feet tall, demands that you use your whole arm to paint. And then you need to stop and step back, often across the room, to get perspective on what you’re doing. You need to juggle and balance, moving constantly around the whole surface, darkening here, obscuring there, sharpening an edge, scraping off a mistake.

The painting is a living thing and the act of painting is all about responding to that life. Sometimes you reach perfection, then fuck it up with an an ill-conceived dollop. Then you battle back from that blunder and the painting turns a corner and brings you somewhere you’d never known could be.

This back and forth went on for a couple of hours till I reached a point where I was afraid to screw things up anymore. I’d painted a man who seemed to be going through something. Writhing, pained, pulled into himself but surrounded by turmoil. It wasn’t what I’d expected and I didn’t know if I liked it. But I was soaked in sweat, dehydrated, and happy.

On my next trip to Blick, I picked out a set of oil sticks. They are solid tubes of oil paint that work like juicy grownup crayons. Basquiat used them and I had always wanted to as well. I had no idea how or what I’d do with them but I sprayed a sketch in red and then started to draw. The juicy sticks are more like lipsticks than crayons actually, a bit out of control, very opaque and bold, but their lines are sharper and less intriguing than brushed paint. So I threw some acrylic on top, only to discover that while water-based paints dry quickly in summer studios, oil sticks take a while to dry and when you rub over them they smear.

Actually, that was good — it made the lines less boring and I started to rub them with my fingers. Soon that was a mess so I added more paint. A man emerged. He had no irises. I painted some in and he became boring so I blinded him again.

The spray paint started to scare me a bit. At first, I only used it on the roof, but then, impatient, I started to touch things up in the studio. I’d spray a layer of paint over the acrylic and the oil stick, knocking the image back a bit so I could then pull out parts of it again. But spraying paint indoors is not good. So I hauled it back to the roof where I fought the sun and the wind.

For the rest of the day, I imagined my lungs filling with paint mist and my eyes caking over with a layer of royal blue. I remembered once, in my early twenties, spray-painting a chair Chinese Red and afterwards looking in the mirror — my nostrils looked like they were leaking blood, my nose hairs struggling like overwhelmed filters.

This memory and the hypochondriacal fears of clogged lungs led me to Home Depot where I bought a spray mask and some goggles. These were really unpleasant to wear on the rooftop and my goggles quickly steamed up on the sunny roof so I was painting blind, but at least I wouldn’t end up with black lung and a ventilator.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

One of the concerns I’d had when I first contemplated getting this studio was what I was doing it for. I knew I didn’t want or need a bunch of paintings to hang in my apartment. I wasn’t going to display the paintings in a gallery, submit them to a show, or show them to anyone at all. But I wrestled with this for a while. I didn’t want to seem pretentious, like ‘look at me, I’m a painter”. Plus, I was sharing my studio with a guy who actually is a painter — Jack, my son, the real thing, trained, newly-minted art school grad. Though I knew he would never say anything about what I was doing unless I asked, I didn’t want to have to worry about whether what I was doing was correct, was proper painting, was art. I just wanted to have fun, slop some shit around, work big, see what it was like.

And then, a few weeks into our lease, I realized I could just throw out everything I was making. Put them back in the same dumpsters I’d taken them out of when the summer was done. I’d snap some pix for a souvenir and then bu-bye. No muss, no fuss.

What a relief! I knocked out a half-dozen portraits of people who live in my skull, experimenting with different media, stumbling, recovering, going over the deep end, surprising myself, and knew all along I wasn’t handcuffed to the results. All process, no pain.

One day, I dove into a dumpster that was full of coffee urns. You know the kind they put in conference rooms, with the stack of paper cups, the pods of creamer, and the dish of wooden swizzle sticks. There were dozens of these abandoned soldiers and I hauled a bunch onto the road. Immediately I saw that they were stocky little men, like me. They had thick legs, barrel chests and protruding spigots. When I opened their lids, some screamed, some yawned, others laughed or just looked blank.

I hauled four of these guys behind the studio building and began to paint them. This was around the time of the political conventions and Donald Trump was all in my head. I found a lamp with a dangling plug and a workman’s glove and added them to the top of one urn, then painted the whole thing bright safety orange. I stood him in the corner of a brick wall and snapped his picture.

It felt a little adolescent but there was also something strangely moving and powerful about this angry little man with a stub of a penis. Later we left him by the edge of the East River, his back to Manhattan, braying with fury.

Another urn got black pants and a white shirt and tie and then I drew on some anguished arms. He opened his mouth wide to howl. Jack and I put him in a subterranean cave we found by the shoreline, then an abandoned hut, then by a smashed car. He said something different in each spot.

I gave another urn a pair of christmas ornament balls and spray painted him matte black. He looked like an ancient fertility statue, something mythical and powerful. We posed him first on a concrete block, then raised him up on a giant, black steel structure high above an intersection where he could looked down on passersby, a little god in a roadside shrine.

Another urn was all-white and we placed him far out in the river, alone on a mooring in the water where he will sit until a strong gusts knocks him into the water and sweeps him out to sea, his mouth agape.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

On the final day, we packed all of the paintings into the car and drove back to Manhattan. It was the first day of the new term at NYU and Jack and I walked back from the garage through throngs of excited freshmen, carrying the stack of huge paintings. Outside the main dorm building, I signaled to Jack. Barely breaking stride, we leaned the paintings against a doorway and kept walking.

Maybe some weird kid took one of my portraits them to hang in his or her room, a souvenir of that first weekend in the big city. Maybe a janitor stuffed them into a dumpster later that day. I’ll never know, nor do I care. They have their life, I have mine.

I can’t be bothered to judge what I made. But I can judge the process. I enjoyed the liberation I felt in the studio this summer. I liked the risks I took, the exhilaration I felt, the battles I waged. I don’t think I’ll be a painter again for a while, but it’s great knowing that beast is in me, that I can make things without premeditation, that the process can be an adventure, that I can step away from the confines of a small page and a book and a little set of watercolors. It’ll be nice to see what effects my exploration has on the next sketchbook I fill.

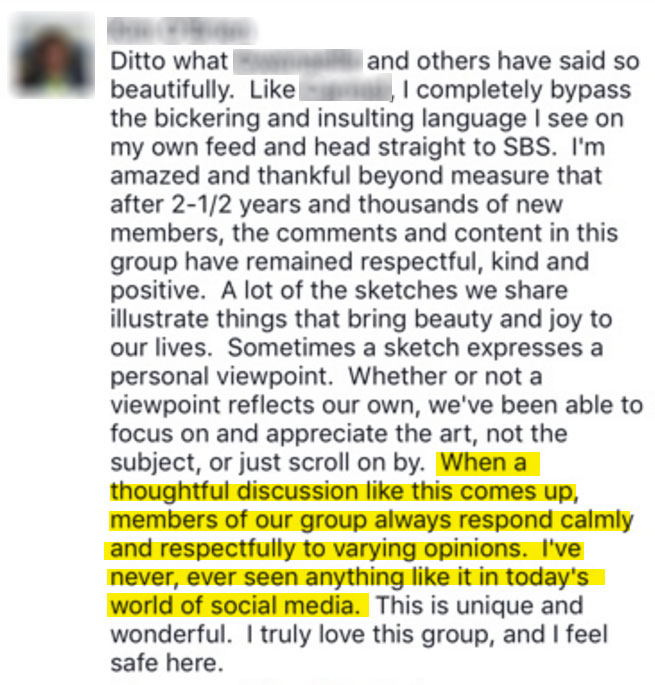

An ever-expanding group of people talked about what the group meant to them after the election. Some of these people no doubt voted one way others probably voted another, but all agreed, that this group was the place they felt safe because the things that had drawn them all together in the past still mattered an awful lot to them: art, creativity, encouragement, a sense of commonality. Many members of the group have told me that they wanted us to keep the group closed because they didn’t feel comfortable sharing their art in their usual social media feeds — they worried that relatives and colleagues would sneer at their burgeoning creative efforts, but in this group they felt like they were among friends.

An ever-expanding group of people talked about what the group meant to them after the election. Some of these people no doubt voted one way others probably voted another, but all agreed, that this group was the place they felt safe because the things that had drawn them all together in the past still mattered an awful lot to them: art, creativity, encouragement, a sense of commonality. Many members of the group have told me that they wanted us to keep the group closed because they didn’t feel comfortable sharing their art in their usual social media feeds — they worried that relatives and colleagues would sneer at their burgeoning creative efforts, but in this group they felt like they were among friends.