When I was in college, I landed a summer internship at the White House. It was a weird time to be there; the Iranian hostage crisis was in full swing, the economy was dicey, there were gas lines and Carter was clearly going to lose the presidency. My bosses at the Old Executive Building were too busy typing their resumés to bother with me and, after a month or so, I quit to work in a sandwich shop in Georgetown.

I didn’t have much connection with Jimmy Carter as a man. He was from Georgia, a born-again Christian, and he tended to the preachy, telling people to save energy by wearing cardigans and the like. He was a decent guy but I couldn’t have told you a single thing he accomplished or wanted to accomplish in the White House. I didn’t feel him, as they say.

I didn’t feel Reagan much. Or Bush Sr. There were times Bill Clinton thrilled me but I doubt I could have just hung out with him. We were too different. George W. was also quite alien to me, born of privilege and Texas football, despite his aw, shucksness. (Ironically, his recent reincarnation as a painter has made me think again).

But Barack Obama was a man I know. Not in the way you might think, or even know him yourself. My connection with him is personal and deep. It wasn’t just because he spoke so eloquently. Or that we are just about the same age. Or that I liked his policies (I actually didn’t like a lot of them and wish he’d been more effectual in so many ways).

It was because I saw many things in his biography that I see in my own, things I have rarely seen in anyone else, especially in American public life. And those things helped to make him who he is and make me who I am. A person who is outside of the norm but has always wanted to be in the middle of it, and who, in his outsiderness understood the idea of the center better than those who were born to it.

Let me explain.

Obama, like me, was born of two very different parents who, like mine, separated when he was a toddler. His father, like mine, was always an abstraction to him, a distant figure whom he only vaguely ever understood. A father who left to start another family in another country and to which Obama, like me, was only an occasional adjunct.

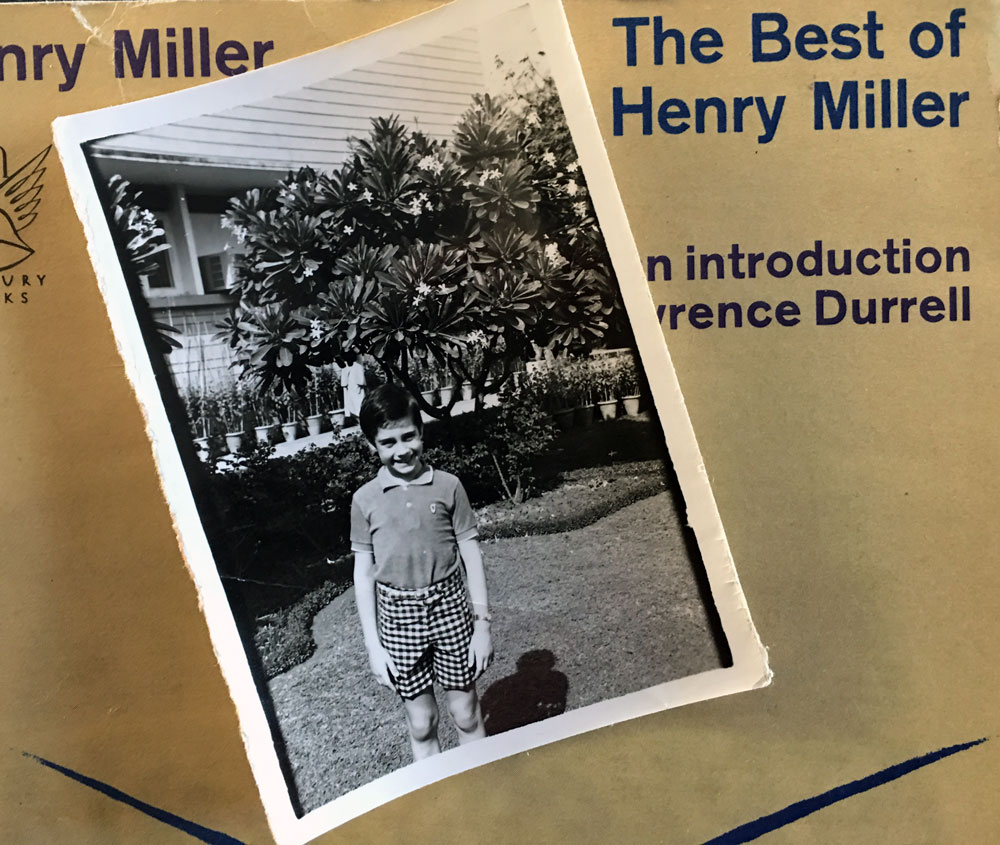

Obama, like me, was raised by his mother, a headstrong and free-spirited woman of the ’60’s, who took him to the other side of the world when he was young and dropped him into an alien culture. In Obama’s case, it was Indonesia. In mine, it was Pakistan (and Australia and Israel).

Obama, like me, was half one race, half another. He is not entirely black, not entirely white. I am not entirely a Jew, nor entirely a Christian. My paternal grandfather was an anti-Semite. My maternal grandfather feared and suspected Christians.

Obama, like me, was raised by his grandparents. His were white midwesterners. Mine were German Jewish refugees living in Pakistan. Theirs’ was his true childhood home. Like mine was.

Obama, like me, grew up feeling like an outsider who wanted to be in. I was always the new kid, who didn’t know the language, the sports, the culture, but desperately wanted to be in the know. We were both ‘third culture kids’ growing up in cultures to which we weren’t born (I mean Indonesia, not the US. I’m no birther!), with mothers who were also alien. My mother was also a third-culture kid herself, so my feelings of dislocation were squared.

Obama, like me, retreated to books for perspective. When you spend your childhood reading to learn about the world, you are often wise beyond your years but also disconnected from the norms of childhood. You are more likely to relate to adults, making you even more alienated from other children. You also tend to think in abstractions, to loftier but more otherworldly thoughts. Books are great but they are not life or people. Books encourage you to dream, to relate to people far away, from distant times, better even than to those who surround you.

Obama, like me, always related to people who were pretty different from the norm. It’s easier to understand people who are also alien when you are raised as we were. When I was in college, my friends were Pakistani, Swiss, Greek, gay, Muslim. In fact, one of my best friends, Binoo Mahmood, was also Obama’s roommate when they were at Columbia. Small world.

When Obama was actually elected President, I was as delighted and surprised as many people. But not because he was black man. Because he was like me, an outsider who was now in the very center of it all. It seemed unimaginable that one could go from pressing one’s nose against the window to being the leader of all these people who I (and I’m sure he) had envied for their normalcy.

When you are an outsider, yearning to get in, you spend a lot of time studying how normal people behave and seem to think and feel. And the more you observe, the better you get at seeing what makes them tick, and you can reflect that normalcy back at them, showing them what it is that makes them who they are. It is not second-nature, it is a studied effort. It’s also not acting or pretend. It is a genuine attempt to blend in, and to do so, you have to study every nuance of what means.

Obama, like me, did a good job of it. (He actually and obviously did a much better job than me. He made it to the White House, a place which has always been a shrine of normalcy even though inhabited by very unusual people. I made it to this blog. )

That’s not a given. Because one could take the opposite tack and embrace one’s otherness altogether, be obviously different, a freak, who’s differences encourage the unity of others, a jester, a scapegoat. Neither of us could have borne that additional rejection.

Obama, like me, hasn’t convinced everyone. Sure, his approval ratings are in the mid 50s but 29% of Americans still strongly disapprove of the job he is doing. And who knows what percentage just disapprove of him, of the idea that an outsider got that far in. They do not accept his apparent normalcy. I know how that feels too. One misstep, one oddly pronounced word, and you can feel the mood shift, the air chill, hackles rise, low throaty growls reverberate.

Obama and I are not the only outsiders in this country or this world. Billions of people feel some measure of this separation. And many of them are artists. Because being an artist always means being other, seeing human experience from a slight remove, a distance that could have its origins in accidents of birth, gender, history, psychology or just chance. Artists see clearly because we have stepped back. And we have the need to express ourselves because our jigsaw piece doesn’t fit quite so neatly into the lovely picture arrayed before us. Our edges are rough or misshapen so we cannot take life quite so for granted. We balk at it, we question it, we make things in response.

Obama, like me, channels his creativity into words. His speeches are lofty but always with one foot in shared experience. He has always been able to take us from where we are to where we could be. But in those words he has also betrayed his otherness and his tendency to abstract what people take for granted. Many are suspicious of this. They see his words as a coverup. They feel his difference in the way he speaks. He seems to think he is better. He may be but more importantly he is other. And in his otherness he has always showed me, at least, that one can strive to be better. One may not succeed but if we always just settle for what is, we will never achieve could be.

Our leaders are not us. They may not be better than us. And in many cases, they are nothing like us at all. But that doesn’t preclude them from knowing what want and need. Otherness makes the best of them see us more sharply and offer clearer direction.

Great leaders articulate the us that we could be. They may not complete the task of getting us there but they can shine a mighty light to guide our way. And it can take time for that articulation to sink in, to convince us that we can be better. One of the great outsiders once said, “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Obama, like me, has always hoped we will all still get there someday.

More than forty years later, I still remember all the publisher imprints, ingrained in my skull from staring so hard at the jackets of all those illicit books. Penguins in orange, blue and green, Faber and Faber, yellow jacketed book from Gollancz, Corgi paperbacks, and the gorgeous bindings of the Folio Society.

More than forty years later, I still remember all the publisher imprints, ingrained in my skull from staring so hard at the jackets of all those illicit books. Penguins in orange, blue and green, Faber and Faber, yellow jacketed book from Gollancz, Corgi paperbacks, and the gorgeous bindings of the Folio Society.