The final leg of our cross-country drive. 4,000 miles, 10 days, loads of eating, driving, drawing, and fun. Click on any picture to see the gallery. Or you can follow me on instagram: dannyobadiah.

Images from the road.

We are driving from LA to NYC. I’ll post pictures from the trip here. Click on any picture to see the gallery.

Or you can follow me on instagram: dannyobadiah.

Farewell.

I finished cleaning out my studio today, this old garage in which I’ve I spent much of the last eleven months. I felt a bit melancholy as I swept it out and locked the door for good.

I finished cleaning out my studio today, this old garage in which I’ve I spent much of the last eleven months. I felt a bit melancholy as I swept it out and locked the door for good.

I came here last autumn not knowing what I was doing or what might become of me, but I felt I needed a place to do it in. And I’ve done quite a bit between these three walls. I picked up a brush again and made forty feet of paintings. I wrote and illustrated a book. And started another. I wrote, shot, and edited films in here. I read books. I thought. I napped.

And we started Sketchbook Skool out of this garage, like real West Coast entrepreneurs. Maybe they’ll put up a plaque.

And now, concrete and wood, it’s going back to being a garage again. But me, I’m not going back to what I was.

Jenny and I are hitting the road today. We’re heading eastward on what was Route 66. Don’t know how long we’ll take to get back to New York. A week, two, whatevs. I’ll try to keep you reasonably updated. Follow us on Instagram: dannnyobadiah

Life story.

Tonight I was thinking about the story of my life. The story that began when I was born and then certain things happened. My parents did certain things, my family was a certain way, we lived in a certain place, I went to certain schools. That was my childhood. In some ways, it was like other people’s childhoods but in other ways it wasn’t. But it was the only childhood that I had.

And then I had my teen years. My adolescence was, what five or six years of my life. They were pretty important years, even though I don’t actually remember that much about them. I remember the first time I kissed a girl, the first time I drank so much I threw up on the subway, the first time I was in a play.

These were all important events in my life. But they were one-time events and I will never have them again. All these events were difficult to judge and put into context at the time. Things happened that seemed incredibly important at the time but now I don’t remember them at all. Whereas other things that seemed trivial have remained with me for decades since.

What I was thinking about tonight was, I guess, this finite quality of my life. Not death, the end, but just the whole arc of my life. Right now I am at a certain point in my life. It feels like it’s probably the middle of my life but I don’t know that for sure — I could be a day away from the end. But assuming it is the middle of my life, I can’t necessarily look at it and see how everything that has preceded it has led to this point. It feels sort of like progress but also somewhat random.

Looking back at those events in the past that had either a significant impact on me or were completely forgettable, I’m struck by the fact that they are so difficult to assess. I look at things that were clearly watersheds, like getting married, having a kid, losing a loved one, but all those events turned out to have a different meaning than I thought they would have the time. It’s just proved impossible to chart the course of my life or even understand it as it unfolds.

So I could look at this very moment, sitting here, a certain point in the summer, when certain events have happened or changes took place, and I can imagine that I could look back on this time and see it for something or other, but right now I have no idea what that is.

The only meaningful way to look at your life is twofold. On one hand, this big sweeping story: I was born, I lived my life, and then it ended. Or the minuscule: one day at a time, one hour at a time, putting down the events of each day in my journal, I ate this for lunch, I talked about that with my friend, I bought new tires, I discovered a lump, I found five dollars on the street. I can’t tell whether it matters, or why, or how much, I can only live through it. And thinking about the big picture reminds me that this is the only time that I will have today, and because I don’t know what role or purpose today will hand I should try to live it fully.

Perhaps this is all just a trite observation. But tonight it struck me that my life is like a TV show and I can pause it and see how much time has passed in the episode so far, but I can’t tell how much time is left. I can look back on what has happened in the episode so far but I can’t change any of it. And what is to come may or may not have as much excitement or laughs as what has transpired so far but I plan to watch the rest of it regardless.

When I look back at what has happened so far, it’s again that feeling that that was my one childhood, that was my one adolescence, that was my one first job, and that’s it. It can make life seem fleeting but it can also show the importance of each one of these sections, including the section I’m in now. And when I think about the uniqueness of this period I’m going through, it makes me want to get the most out of it, to not take it for granted but to live it deeply, richly, cause this is the one I have. ‘One Life to live’, so I guess in the end, yes, the conclusion is trite. But somehow, tonight, that didn’t make It any less true or less important to think about.

Oh, and I know my blog looks different, You’ll get used to it. So will I.

Why it doesn’t look just like the picture.

In the 1980s when photocopying technology became increasingly available, David Hockney made a series of prints using a Xerox machine. I was looking at some of these prints recently and trying to overcome my initial dismissive reaction: these aren’t ‘prints’. But of course, they are. They were state-of-the art prints in their day.

In the 1980s when photocopying technology became increasingly available, David Hockney made a series of prints using a Xerox machine. I was looking at some of these prints recently and trying to overcome my initial dismissive reaction: these aren’t ‘prints’. But of course, they are. They were state-of-the art prints in their day.

Printing is and has always been a mechanical method of making multiple reproductions of an image. In the past artists used woodblocks, etchings, engravings, then lithography, screen printing and so on. Today, many artists sell giclée prints of their work, prints that are digital scans of their drawings which are then processed and printed on inkjet printers. And what if we skip the paper part of it all together and use an iPhone and a distant computer server. Isn’t that basically the same idea?

Our instincts say no. It’s somehow not hard or special enough. Where’s the craft? But of course a good digital scan take experience and tools and work. So that’s not it. Or maybe it’s posterity, the sense that an old Xerox or a computer print out surely won’t survive for hundred of years like a Dürer woodcut. But with archival papers and inks and proper handling, that’s probably not the case either.

No, I think the real issue is scarcity. If you can just push a button and bang out an infinite number of reproductions, it is no longer precious, a limited edition, valuable. If someone can make an infinite number of copies, then there’s no value to any particular one. A Work of Art is reduced to the same status as a call report or a lost pet flyer. So the Art Market has trained us to dismiss this way of looking at it. If it can’t be bought or sold for increasing amounts, don’t bother making it.

Now, if inventive, creative, curious people like Dürer or Rembrandt had been able to make thousands and thousands of copies of their images with just the push of a button, believe me, they would not have been sweating over blocks of wood. They weren’t burdened with the same market concerns that weigh down our view of art. They made limited editions mainly because it took a helluva lot of work to get even a dozen proper prints from a copper plate.

But that’s not what I want to talk about.

Thinking about Hockney’s Xeroxes made me think about how technology is constantly improving the ways it solves basic human problems. Not just labor saving devices, but things that make our lives better and richer. Examples abound.

But what about image making? There was a point when people drew on cave walls with blood and mud, to make some point lost to the sands of time but they were using the best image-making technology they had. Eventually we figured out how to carve stone statues, to make fresco, to stretch canvas, and so on.

This image-making and image-sharing had a purpose. Usually it was to tell a story or pass on some vital information: this is what the Gods did, this is how we won this war, This is how handsome and powerful the King is, this is how Jesus came back, and so on. Nowadays, if Jesus came back again, we would probably use Vine or a Facebook post to share the news, not a fresco or calligraphy on a goatskin.

So if, in one split second and with no real experience or skill, you can use the phone in your pocket to make an image that is technically superior and precise to anything you can make with pencil, why make art at all anymore?

That’s a question people have been asking themselves for almost two centuries. And the answer that Manet and Monet and Seurat and Cezanne and Van Gogh and the rest of the gang came up with over a hundred years ago is that the purpose of art is no longer to reproduce physical reality, it’s to convey how we feel about it. To capture the human condition, the way we see the world through the veils of subjectivity, experience, emotion, history and all the rest of the stuff that make us who we are.

This is something we have to think about when we draw. Stop assessing your work based on how close it is to “reality”. Don’t bother posting a snapshot of your dog next to the drawing you did of it. Who cares if you are almost as good as that camera in your pocket. ‘Cause in fact, you’re not even close. That photo is a far better way to make that image. More efficient, more accurate.

But that image isn’t really what you want, is it? What you want is to capture your soul, your inner state, the love you feel for that dog. You want to make a picture of the inside of your mind.

Don’t worry about Xerox®ing reality with your sketchbook. Focus on capturing You instead.

So far nobody, in Silicon Valley or elsewhere, has come up with an app for that.

Pulling my head out of my head.

Miles Davis’ quartet is working How Deep is the Ocean a few feet away. I have an almost drained but still frosty glass of pilsner next to me on the window sill. There’s a slight breeze coming through the open window, 76 degrees, just a hint of humidity. My neighbor is roasting a chicken, smells like some tasty ‘taters and broccoli too.A cab pulls up to the stoplight downstairs, and I can year the Yankee game on his radio, there’s a pitch, a swing, and then the light changes and the game pulls away. I am just a teeny bit light-headed from the cold beer, the first I’ve had in days.

This is the sort of moment I dreamt of in January, or in a too-long meeting, or in a middle seat to Godknowswheristan, this exact sort of moment — living is easy, all’s right with the world, summertime, deep sigh.

But this moment is only here because I suddenly let it be, put down my book, closed my eyes, felt the breeze, smelled the chicken, heard the ball game. I hadn’t noticed ten breezes, ten chickens, ten cabs before this one, hadn’t heard Miles’ last ten tunes, hadn’t tasted the last ten sips of beer.

And that’s the danger of living in my head, of not being here and now, of wishing for summer when summer is here, of missing her when she is in my arms — the voracious tyranny of imagination and distraction, of the mental life, of modern life, of mature life, of the whole parade passing by as I am busy making plans.

Time to wake up and smell the chicken.

A major new interview

There’s a major new two-part article/interview with me about SketchBook Skool.

There’s a major new two-part article/interview with me about SketchBook Skool.

We really got into the ideas behind the Skool, what I think about art, why it matters — a lot of new stuff. It was an interesting process and I am really pleased with the piece.

How to fight a critic.

It’s tempting to fight back against criticism. But where does it get you?

Take Manet, the father of Impressionism. Outraged by a critic’s attack, he challenged him to a duel. They met in a forest, hacked ineffectually at each other with swords until they bent them, shook hands, and limped away. Neither man was badly injured and they both went back to work.

Take Whistler, a bad-tempered and thin-skinned genius whose memoir is called “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies.” When John Ruskin wrote an especially vicious review of one of his paintings, Whistler took him to court, strenuously defended his modernist aesthetic — and was awarded a farthing for his troubles.

In the long run, both men beat the critics with a different weapon — the brush.

Manet is known for launching impressionism, for making it acceptable to paint everyday life, for Olympia, Le Dejeuner, and the critic, well, his name was Edmond Duranty—ever heard of him? Whistler’s legacy is bit more ironic, due not to his critics but to fans of his most famous work, “Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1.” After spending his life fighting against art based on moral lessons and maudlin emotion, he is known for a painting of his mommy. But it is a great painting and, even after the trial, he continued making many more.

Critics, internal and external, can raise any artist’s hackles. They can provoke you into violent defense of your work, into self-doubt, even into halting your creativity all together. One man’s opinion, published in a newspaper, or muttered in a gallery, or imagined in a moment of weakness, can suck up your energy and threaten your creative life. Few critic’s opinions endure and that’s something to remind yourself of. Because opinions are products of the moment, influenced by current trends, by ignorance, by poor digestion. They are not eternal, objective, blanket truth.

Any condemnation of a work of art, whether it comes from a professional, from a neighbor, from a monkey’s voice in your head, should only be responded to with more work. Prove them wrong — if you have to acknowledge them at all — but never let them get you down.

Forget lawyers and swords. Make your case with a brush, a pen, a blog post.

Why do I like?

To me, the most interesting art isn’t necessarily well-rendered, accurate, realistic. Often, quite the contrary.

To me, the most interesting art isn’t necessarily well-rendered, accurate, realistic. Often, quite the contrary.

So, what does make it interesting? What are the qualities that make me like a work, my own or someone else’s?

This seems important, so let me think on it a bit.

First of all, specificity. A drawing that is of a very particular thing. Not just a car, but a specific car with all its dings and reflections. A car that looks like it was really studied by the artist. It’s true in all art forms, in a documentary, a novel, a record. The little details that make me know more about the subject.

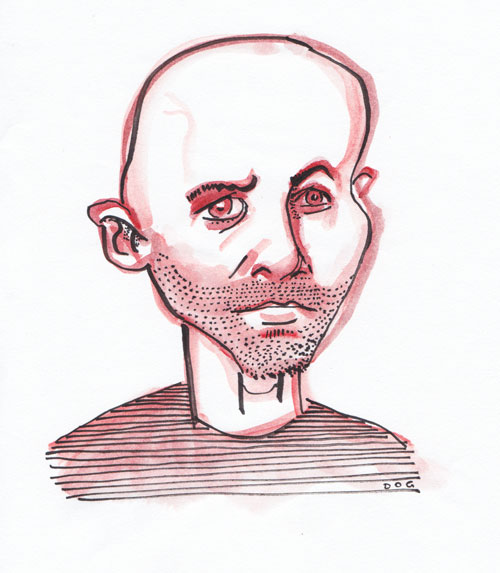

And it’s not just that the artist noticed and captured the specifics of the subject, it’s also the specifics of how he or she did it, the feel of the hand behind the pen, the little eccentricities that make it original, the catch of the pen on the paper, the oneness of the particular piece, the particularity of the personality and the vision behind the line.

That’s why I like a recording where you can hear Segovia’s fingers squeak over the metal strings of his guitar. Or the recognizable grit of a specific New York street corner in 1970 in Panic in Needle Park when Al Pacino crosses Amsterdam and 86th early in the morning and you can just smell it, taste it. A Ronald Searle drawing that has splashes and blotches of ink and redrawn lines. Karl Ove Knausgard’s amazing novel, My Struggle, bringing to life the tiniest, most specific details of everyday memories to give the mundane deep meaning.

Art that is too perfect, Photoshopped, processed, loses this specificity. In fact, any reproduction lacks these little specifics. That’s why seeing an original is always a completely different experience, even if the image seems familiar. When I looked at a pyramid of Cézanne’s oranges in a Google image search, I get the gist. But when I see them hanging on the wall of the Met, I get a feeling, a series of revelations as I see more and more through the varnish. I have the opportunity to explore deeper and deeper with my eyes, to see layers and brushstrokes that the “image” alone doesn’t convey, the way the paint that Cézanne chose and placed does when it’s sitting right in front of me. The specifics.

When I draw from a photograph, it’s often impossible to get that deep sense of seeing, to see the particulars on a deeper and deeper scale. All too soon, I hit grain, pixels.

For me, drawing is an opportunity to avoid the clichés and the symbols and to focus on what is really there, warts and all.

Story is another aspect of specificity.

Not an illustration per se but a drawing that captures my imagination and starts a movie in my head. A captured moment that evokes a bigger context, like any painting by Hopper. Or shows the marks on a object that tells you where it’s been or what’s done. The lines and wrinkles on a face that are a roadmap, a drawing that become a biography.

Scale is another way to add interest.

To zoom in tight on something and see it afresh. The details of a butterfly’s wings, a bagel’s crumbs, a bicycle’s greasy chain. Or to stand way back and see it in a different context. To look at the Empire State Building poking out on the horizon from behind a row of four-story brownstones. Giant blades of grass on a lawn and a tiny plane in the sky way above. A page crammed full of tiny drawings of giant trucks.

Interesting art also contains a surprise.

It could be in the lines themselves, lines with an unusual but true thickness or movement. A variety of sweeping brush strokes and then details in fine pen lines. Inconsistencies that draw my eye and, with a moment’s reflection, become a revelation.

In color: Complimentary colors, A wash of liquidy teal watercolor and a tiny, sharp spot of orange gouache. Unexpected shades. Purple cheeks, orange eyes, a green sky.

A wall of perfectly drawn bricks and then a hastily drawn broken window. A third ear that lets me in on the artist’s process, a reconsideration, a redrawing.

Elements that make me pause, break my assumptions, jar me into reconsideration. The art in startle.

None of the above are rules, just springboards that can turn ho-bummery into something fresh and exciting. Or can help guide me in understanding why I like or don’t like the art in front of me.

Are there more? You tell me.