I’m a big, fat vat of soup. Deep below my surface, I am roiling, ingredients churning, interacting, breaking down to add flavor and texture. Sometimes I’m hot and bubbling, giving off a delicious aroma. At other times, I’m tepid and lifeless, the gas off, a greasy film forming, unappetizing, dull.

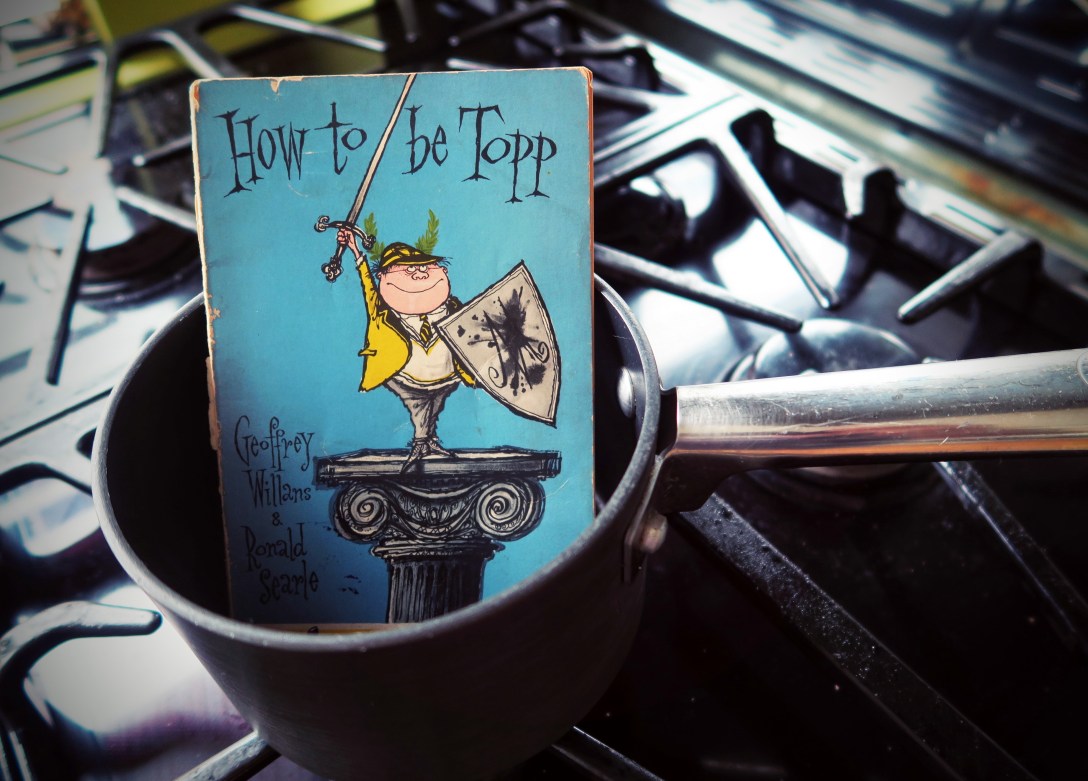

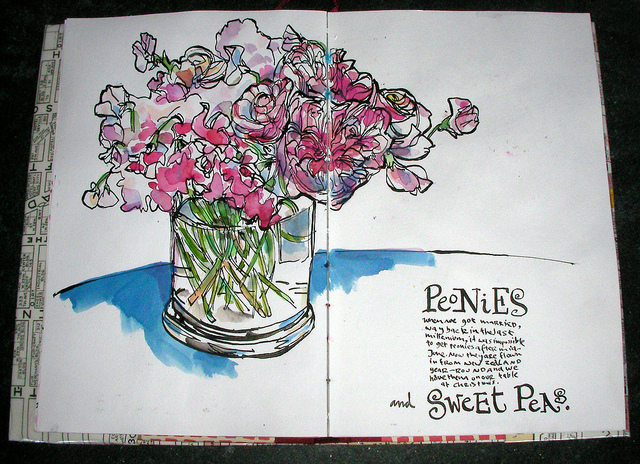

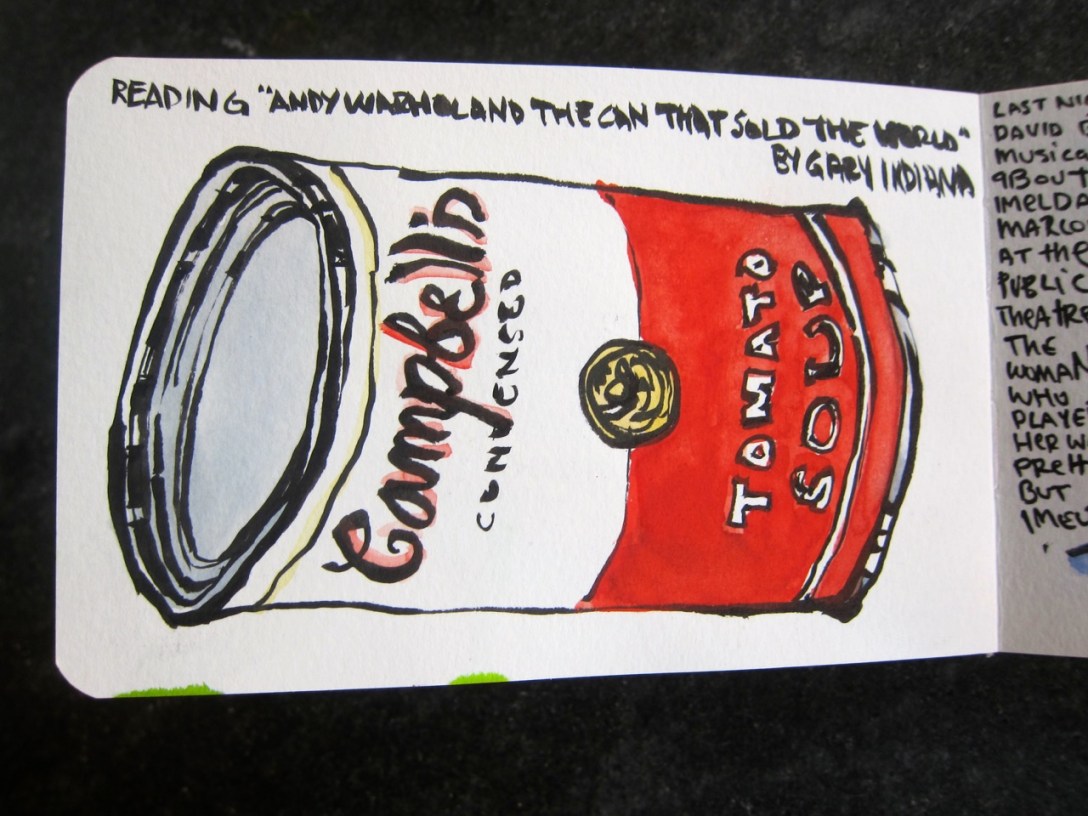

What’s in the soup? Well, let’s dip in the ladle and fish out an ingredient. Ooh, it’s a book I’ve owned since I was eight, dog-eared and well-thumbed, its browning pages loose in the binding. How to be Topp is a satire about success written by a fictional school boy. It’s a fairly silly book and I don’t think I’ve ever read it all the way through. But it was illustrated by Ronald Searle and its pages are full of splatters, spidery calligraphy and loose, scratchy drawings. I may not look at this book for years but it’s in the soup, adding its flavor.

When I was eight I read a lot, several books a week. It’s a pattern I have kept up ever since. Each of the many books stacked on many bedside, in my Kindle, on my phone, and my desk, all end up sliced, diced and scraped into the soup. Many of them break down completely, their pages diluted, vanishing from memory. But each sentence, like a single granule of salt or a delicate frond of dill, though disintegrated, has added a few more molecules to the flavor and body of the soup that is me.

There are the Grove Press books on the top shelf of my grandfather’s study, “grownup up” books I climbed up to purloin and read in private. There are all the Gerald Durrell books that fed my fantasies about raking through the jungles of Borneo and Brazil for aardvarks and toucans, kitted out with a solar topi and a butterfly net. There are 92 volumes of PG Wodehouse, Professor Branestawm, Raymond Chandler, Geoffrey Chaucer, Spiderman.

There’s the girl I kissed in David Heller’s basement in 1975, the bucket of coffee cooked over a campfire on a patch of Israeli wasteland one dawn, the snow boots my mother made me wear that were too big and made me trip over every hummock of snow in downtown Brooklyn. There’s my dog Pogo’s third litter of puppies, two stillborn. The boss who yelled at me while eating an egg salad sandwich. My first Rapid-o-liner. My second stepfather’s broken toe when he kicked in the door of my mum’s MGB. All are bobbing in the drink, coming up to the surface, then subsiding like Moby Dick into the darkness below. There’s Moby Dick, Holden Caulfield, JJ ‘Dynomite’ Walker, the English Beat, my Latin teacher, Jenny’s stuffed hippos, Jack’s soccer cleats, my Pakistani orthodontist.

My soup is rich and complex and like none other, a unique combination of stuff that has been cooking for decades. It contains some ingredients found in your soup, maybe lots of them, but the way they interact with the rest of the bits and bobs bobbing around is all mine, all me.

This cauldron of soup is the source of all I create. If I write a story, make a drawing, come up with an idea, it’s all because of this big bubbling vat of experiences and influences. If I neglect the soup, forget to add new spices, fail to stir it up and fill some new bowls, let the pilot light go out and the temperature cool, the soup becomes anemic and tasteless, a bland consommé that’s forgettable and without value. But if I work the soup, it fills me up.

Being an artist or a writer means reading, looking, listening, cribbing, copying, from a zillion sources. That’s much of our job. These slices of inspiration may have disproportionate effect when they first enter the soup, big undigested chunks that are too obvious when they show up in the work. But over time they break down and dissolve, leaving only ripples that intertwine with others to form a new flavor note, subtle and unique.

We are all vats of soup. Make sure you tend yours, stirring and adding new ingredients every day. Keep the hot on medium-high and take the lid off now and then. And don’t be afraid to dish it up to share with others, to pour a few tablespoons into their tureens. I want to taste your soup. Here’s a spoonful of mine.