If we want to understand what our earliest ancestors were like, our best evidence are the paintings they left deep in the caves of Southern Europe. When we think of Ancient Egypt, we see the paintings anonymous artisans made on sarcophagi, grand sculptures like the Sphinx, monuments like the Great Pyramids at Giza. The Greeks and Romans are represented by marble statues and architecture too. The Medici, all-powerful merchants live on, long after their last pennies were spent, as sponsors of da Vinci and Raphael. Popes like Julius and Leo, who led armies and converted millions, are instead remembered by Michelangelo’s creations.

And when our civilization is over, what will represent us to the future? When every company on the Fortune 500 has vanished, when the borders of all the world’s nations have been redrawn a hundred times, when our glass and steel towers have tumbled, when hard drives have been wiped and silicon decayed, what will stand as our legacy? Will it be our wars, our laws, our economy? Or will it be Walt Whitman, Bob Dylan and George Lucas?

When I visited the Jewish Museum on Prague and saw all those pencil drawings by children long since consigned to the pyres of Auschwitz, I felt their spirits, felt them enter and inhabit me, felt them live on through those faint marks on paper. Hitler should have been more diligent in burning those drawings too, if he was so hellbent on wiping those children from the earth.

When I think of my grandparents, I don’t think of their success as doctors, their accumulated capital, their role in their community — I think of my grandmother’s garden, designed to look like a Persian carpet, her roses, her topiary of a peacock, her frangipani trees and her cacti. I think of my grandfather’s short stories about his childhood in the stetls of Poland and his experiences in post-partition Pakistan, all written painstakingly at his walnut desk in a cloud of pipe smoke, then hand-bound between shirt cardboards.

My grandfather would have been 106 this week. His body is under Mount Olives in Jerusalem. His house is occupied by strangers. His friends and siblings are but dust. But his stories live on in the archives of the Leo Baeck Institute.

Long after your will has been executed, your real estate dispersed, your Instagram feed expunged, the drawings you make, the recipes you write down, those are the things that will keep your spirit alive.

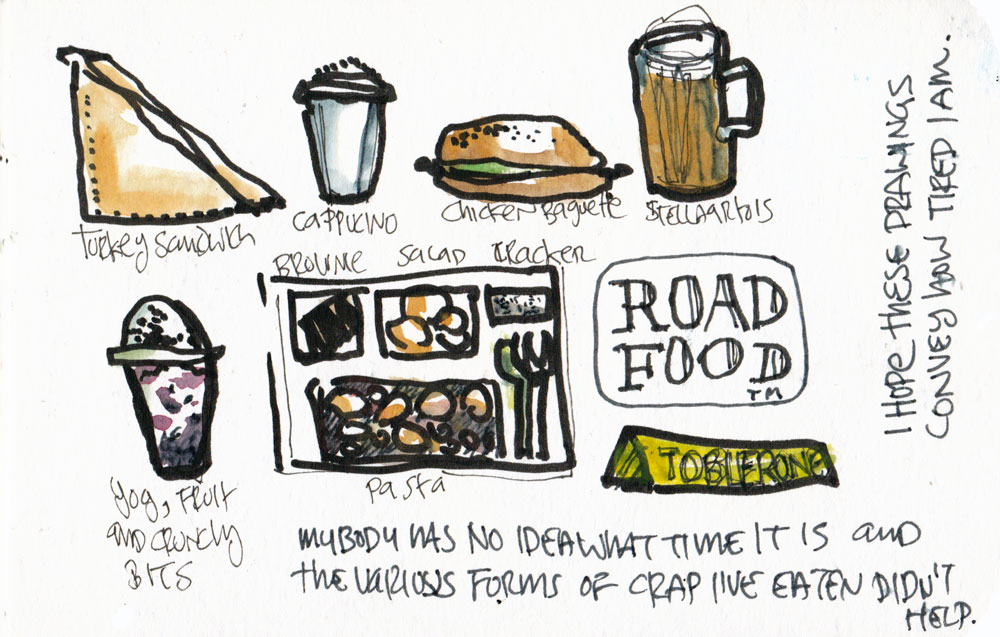

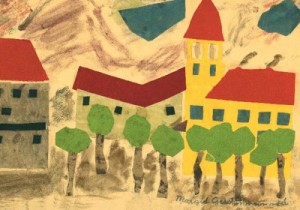

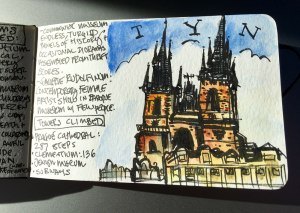

Art is our way to immortality. Long after your will has been executed, your real estate dispersed, your Instagram feed expunged, the drawings you make, the recipes you write down, those are the things that will keep your spirit alive. Your illustrated journals, records of what you did and experienced and felt, they will be your mark on this earth.

Make sure your family understands that your art is you. It is not to be consigned to eBay or the dump. It is the most precious part of your legacy and it should live on.

Oh, and make sure that the monkey doesn’t prevent you from making those pages, from creating the art that will keep your spirit alive. Don’t kill your memories before they can be born. Be brave, be creative, rock on.