The VR thing is a little hokey but I love the way Keane talks about drawing and creativity. He’s like a big kid with a cool new toy.

Tag: Drawing

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell?

This is annoying as hell. My dogs, Tim and Joe, are obsessed with the trash chute in our vestibule. Whenever I drop a bag of garbage down the chute, they go nuts, growling and barking and trying to leap up and into the chute in pursuit of the disappearing bag. This has been going on for years. In fact, it’s so obsessive that whenever we open the garbage can in the kitchen or even the dishwasher next to it, they go scrambling to the chute, waiting for something that’s just. Not. Going. To happen. It’s a habit, a pure, Pavlovian habit.

Habits can be a pain, like biting your cuticles or forgetting to floss, but they can also be a real boon to a creative person. They are a little subroutine we can plug into to our neck-top computers to make sure we draw or write or play the dulcimer on a regular basis, a basis that will make us more skilled, more expressive and happier with our work.

Habits have three basic parts. First, there’s what I call ‘the Spark’. That’s the event that triggers the habit. In my dogs’ case, it’s anything to do with throwing out garbage. Garbage in, the madness begins.

Next, there’s the habitual behavior. In this case, running like a lunatic across the apartment and gnashing your teeth at a small steel door in the wall.

Third, is the reward. Tim and Joe never actually get the reward which must be diving down the garbage’s burrow to throttle it deep in the ground (they are dachshunds after all, bred to kill badgers in their lairs). Or maybe it’s just the thrill of the chase.

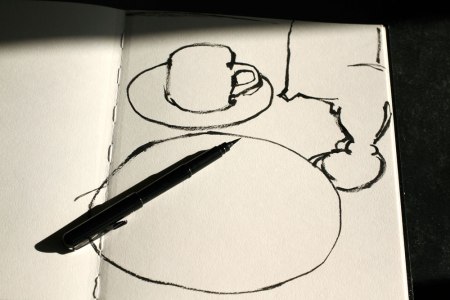

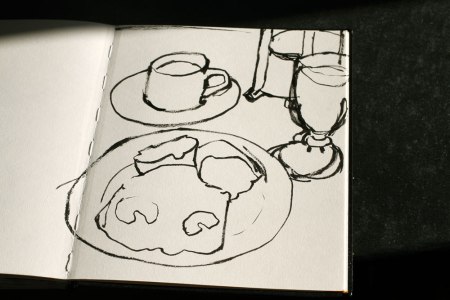

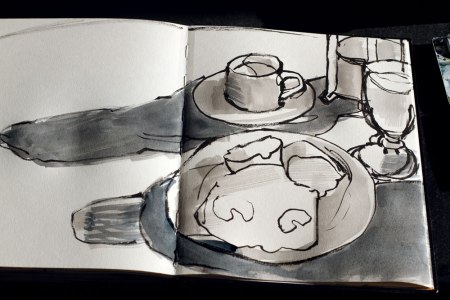

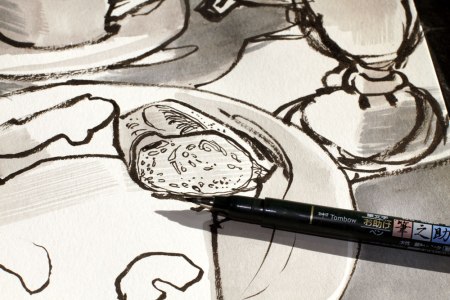

In any case, think of those three steps in setting up whatever brain program you want to write. Let’s say you want to find time to draw on a regular basis but the monkey voice in your head tells you to watch TV instead. So let’s create a habit. 1. Put your sketchbook on the coffee table next to the remote. When a commercial comes, (spark), grab the remote, mute the TV, pick up your sketchbook and draw whatever’s in front of you (your feet, your coffee table, your slumbering Rottweiler, scenes from the commercial on the screen) (habit) until you fill you up your sketchbook with awesome drawings (reward).

Think of other sparks you could link to habits. Every time you make a pot of coffee (spark), draw the view out the kitchen window (habit). Every time you sit on the toilet (spark), draw on a sheet of toilet paper (habit). Every time Donald Trump says “Mexican”(spark), draw your neighbor’s Chihuahua (habit).

Or, subscribe to my blog (sign up in the column on the right) and get an email three times a week when I post (spark), and do a drawing based on my featured image (habit). That will be rewarding for us both.

Rethinking my story.

Earlier this year, I got a lovely invitation to come out to Phoenix to talk about what I do. Jenny was born and raised there so we travel to Arizona at all times of the year to see her family and I have come to quite like the city and the desert. Besides, it was mid-winter and the idea of the desert in August had a powerful appeal.

The climate was not the only allure. Some of my pals like Jane LaFazio and Seth Apter will be there too. But most of all, it was as an opportunity to turn to a fresh page. I decided to use the invitation as an incentive to think of a whole new approach to talking to groups of people about creativity. I often present my ideas on creative blocks and the struggles we have with drawing as adults but, over the past couple of years, I have wanted to think about illustrated journaling from a different vantage point.

As part of this fresh start, I went back through every page of my illustrated journals in chronological order. From my first tentative collages and chicken scratching, through the books I bound myself, through my trips around the world, my experimentation with media, my growing confidence, Patti’s death, Jack’s departure for college, the move Jenny and I took to LA and so much more. I paged through almost twenty years of life and it was exhilarating and sobering, emotional and revelatory.

Now I have managed to turn all those pages into a brand-new story that I am really excited to present.

My presentation is open to all and the folks in Phoenix have set up a lovely evening with wine and desert and such — but reservations are filling up fast. If you’d like to come, meet some other great creative people and see what I have concocted, I’d love to see you there.

The evening begins at 7:00pm on Saturday, August 8 MT. To find out more and register, click here. There’s also a Facebook event.

I hope to see you there!

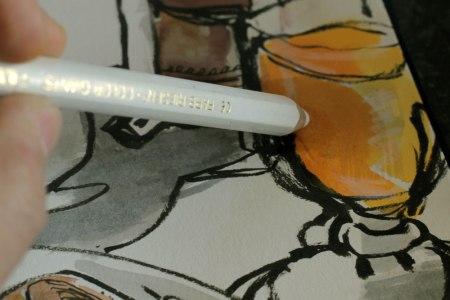

Keeping the fun in fundamentals.

Teaching yourself to make art is a lifelong endeavor. Books and courses will help but it’s up to you to keep the work interesting and relevant.

Look for creative ways to keep practicing the basics, like contour drawing, proportions, foreshortening, tone, shading, volume, etc.

Don’t make drills dull. Find ways to mix things up. Draw things that mean something to you.

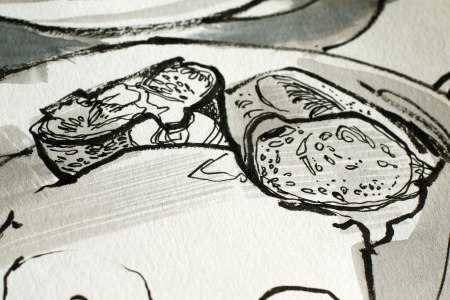

Instead of setting up artificial subjects like bowls of fruit or vases of flowers, draw the contents of your fridge. Draw the roses you got for your birthday and write about how you feel getting a year older. Instead of drawing naked strangers in a life drawing class, draw your naked spouse, your cat, your boss. Rather than doing “Drapery studies,” draw the shapes your feet make under the covers on a Sunday morning.

Be inventive. Be fresh. Be personal. It’s an adventure, not a chore.

Monkey break

The Stare Master.

What were the very first things you ever learned? Unless you are Mozart, they were probably things like walking, talking, using a spoon and a sippy cup. You learned these skills from someone who knew how to do them well, like your mum or your older brother. And you learned them by watching, watching intently. Check out how a baby or a toddler watches — it’s like a lion on the veld or my dachshunds as we unpack groceries. Unblinking, rigid with attention.

Oh, and speaking of Mozart, how do you think he became a prodigy at three? He watched his older sister take harpsichord lessons and he watched his father play the violin. It’s no coincidence that so many prodigies, from Michael Jackson to Wayne Gretzky, were the youngest kids in large families. Lots of people to stare at and learn from.

When you learn this way, you create a vision of yourself performing the skill, a mental video you play over and over. As the scene loops, it is burned into your brain, creating new neural pathways and locking in the nuances of the skill. You notice not only the steps the experts take but the intensity and rhythms with which they perform the action, the way that all the component parts of actions come together into one cohesive and coordinated whole. In time, these observations lead to fluid and confident motions.

Learning a physical skill is a very complex process, most of it nonverbal. You are programming your head and body to dance together in a thousand little ways. You must keep refining those dance steps, polishing them until there are no hitches or hesitations, until they run like greased, teflon-dipped clockwork. That’s how you learn to walk, to dribble a soccer ball, to drive a car, to play the guitar, and to draw. You program neurons.

If you want to improve your golf swing, watch Ben Hogan on YouTube. If you want to improve your jump shot, watch LeBron during this week’s NBA finals. If you want to improve your drawing, watch any of my Sketchbook Films or the demo videos on Sketchbook Skool. Watch them again and again. And don’t watch passively, like you were dozing off in front of a Seinfeld rerun. Sit forward, engage, focus, mimic, stare. Let your body respond as you watch. Feel your muscles tense, your fingers twitch. Throw yourself into it and absorb the rhythms, the linkages, the unspoken logic behind the scenes.

Your meat computer takes longer to train than silicon chips, but it lasts longer too. Once you have forged these connections, they will last a lifetime. Neglected, they may get rusty and overgrown, but, with a little practice, you can prune them and get them up and running again, like a long forgotten stretch of railroad track. You never fully forget how to ride a bike. And the same holds true for the network you’ve built between your brain, eyes, and hands so your pen will make lovely marks in your sketchbook.

Stare, engage, mimic. And repeat.

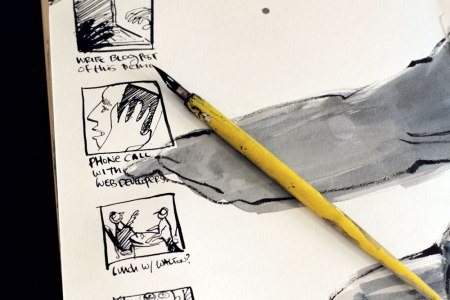

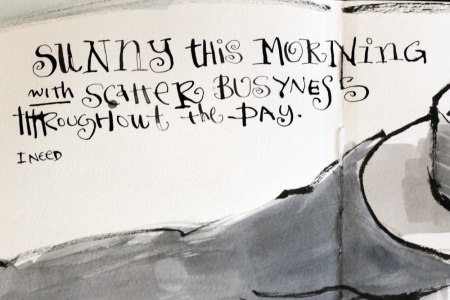

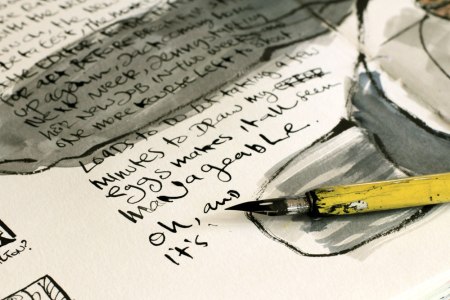

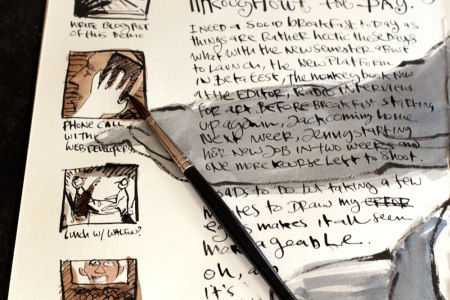

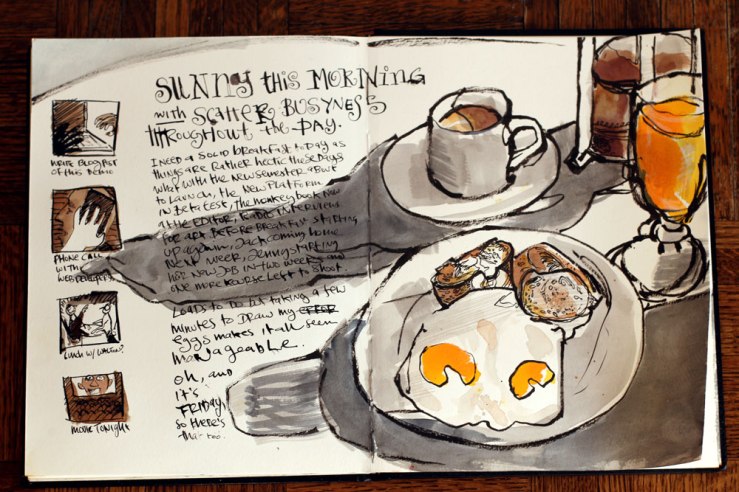

How I make art before I make coffee.

Recently I was invited to participate in a lovely series called “The Original” Documented Life Project™”. Guest artists are asked to document their process in making a piece. I was emailed the following assignment:

“The theme for this month is ‘MAKING YOUR MARK (DOODLES & MARK MAKING). The art challenge for this week is ‘AS A FOCAL POINT’, and the prompt is ‘COMING INTO FOCUS”

I’m not always awfully good at following assignments so I just sort of did what I do. I hope they like it.

* I love Kevin’s latest.

Baby steps

When I started working with Keith, I was not in great shape. I had pains in my lower back, carpal tunnel syndrome, and chronic headaches. But I just grinned and bore these maladies. As far as I was concerned, these were just part of being me, aches and pains that I’d developed since I’d first started pounding on a computer all day, decades before — my imperfections, unfixable.

As for going to a trainer, well, that was all very well, paying someone to hold my hand while I walked around the gym, counting off reps, giving me encouragement, helping me build my biceps or lose a few pounds. Eventually, there were some meager results so I could take it or leave it.

Keith taught me otherwise. He showed the point of exercise is not six-pack abs or marathon times. It’s about making the most of the equipment we have for living out the rest of our days and that making certain little changes could make huge differences to my body and to my life.

We worked on tiny muscles hidden deep along my spine and between my shoulder blades. We focussed on the exact angle of my tailbone when I crouched, correcting and re-correcting. We looked at the angle of my pelvis in the mirror. We rolled the fascia alongside my left thigh with rubber logs and built up strength in my right quadriceps.

After a few months, standing and moving in a balanced way became second nature. The unnatural way I had held my shoulders, my neck, my stance, were replaced with alignment. Now if I hunched my shoulders or sat in a cramped and twisted way, my body told me something was wrong and I adjusted.

My headaches vanished. My hands no longer tingled. My feet, which had always splayed out like Charlie Chaplin lined up toe to heel. My carriage grew more and more erect. Jenny noticed that I was getting taller, soon by a couple of inches. I felt better all the time. And happier too.

For the first time, my relationship with my body changed because I saw what truly is. Not just a couple hundred pounds of annoying meat but an amazing machine that just needs to be tuned and maintained.

I discovered that my body is a miraculous system of complex interconnected processes that can be adjusted, honed, perfected. The way I was didn’t have to be the way I’d be. The unhealthy adaptations I’d made to certain chairs, desks, sidewalks, stresses, ways of standing, sitting, sleeping, were not carved in stone. And my assumptions about my physical being, that it was some sort of curse to be endured, an uphill battle that would always let me down, was nonsense. Being out of whack, behaving in ways that hurt me, limiting my ability, assuming that there was no solution — all these behaviors and thought patterns were replaced by balance and a better way of being.

For the first time, my relationship with my body changed because I saw what truly is. Not just a couple hundred pounds of annoying meat but an amazing machine that just needs to be tuned and maintained. Not for vanity but because of how it helps me live better and get the most out of each day. A few small adjustments in my body led to a change in my entire being. In my life.

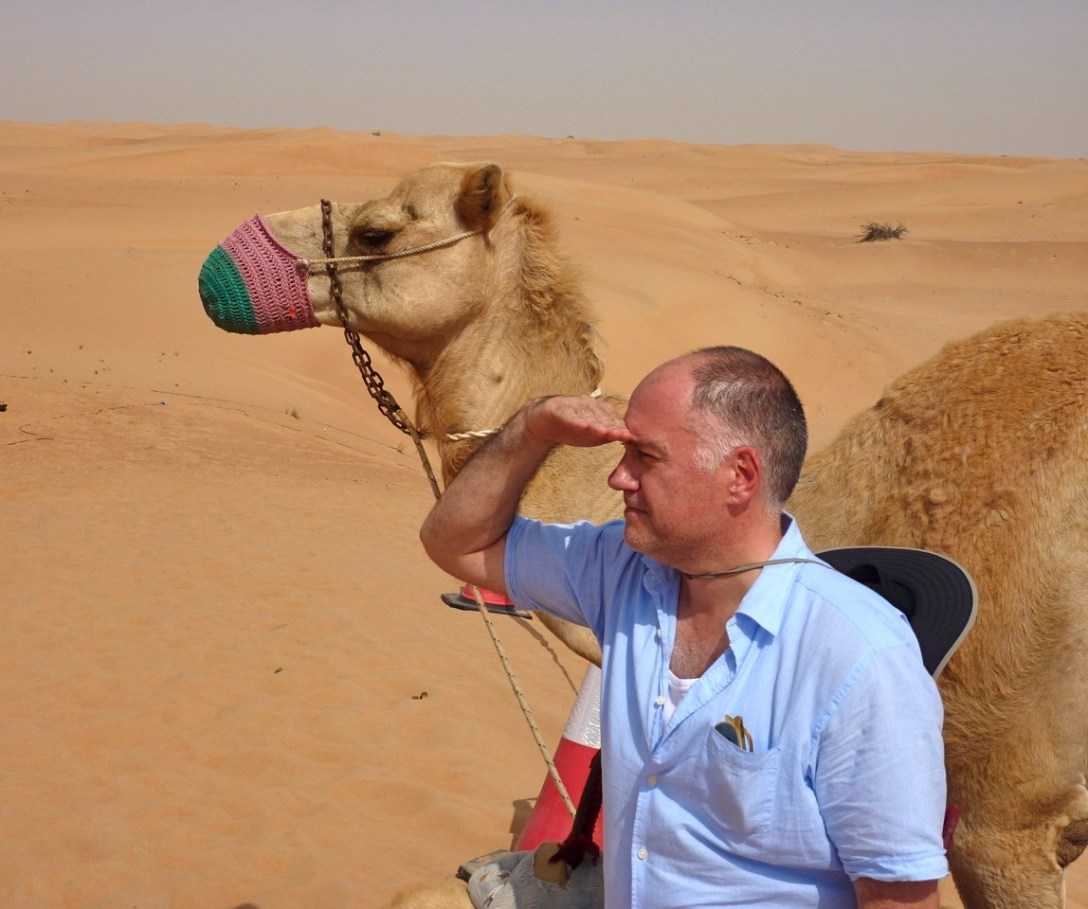

Similarly, when I began to draw, I had no idea what seismic shifts this small change would cause in my life. Many of friends tell me that picking up a pen and opening up a sketchbook ultimately led them to change careers, travel the world, publish books, make new friends, new priorities, new plans for their remaining days.

Why? Why does this simple habit make such a difference? When you start to draw, you set things in motion. You start to see what is. Perhaps you’ll see beauty where you overlooked it. Perhaps you will fill books with stories about your life, an ordinary life, and suddenly see it is actually quite rich and wonderful. And perhaps the power of seeing so clearly will make you want to go and see more. And that desire will cause you, like Mole in The Wind in the Willows or Bilbo Baggins, to lock the door of your cozy little life and wander out into the wide world.

Maybe seeing clearly will show you that you have been hiding your true self from yourself, have been leading a life that wasn’t really what you wanted, that you could do more, that you could be more. That your childhood dreams are still valid, that your parents, your banker, your boss, your children can’t call all your shots. And that time is running out.

When you make art, you slowly brush the cobwebs from your inner life and sunlight starts to stream in. Who knows what it might reveal?

Maybe you will see that drawing is a thing that you actually can do even though the monkey has too long told you that you can’t, because you suck, because you have no talent or time. And, when you discover this power, you may come to wonder what else you have overlooked or deceived yourself about, what else you can do and be. Maybe you could paint or play the piano or visit Rome or hang-glide or open a store or be a clown or run for Prime Minister. Or hire a trainer and get rid of your headaches.

This can be scary, feeling the first winds of freedom and change sweeping through the open door of your golden cage. But if you don’t face this fear from some angle, how can you ever see your life for what is and can be?

When you make art, you slowly brush the cobwebs from your inner life and sunlight starts to stream in. Who knows what it might reveal? Who knows what journey you are about to embark upon once you uncap that pen and take that first little step? Don’t you want to see?

My new book trailer!

The awesome new trailer for my awesome new book! (Thank you, Manny!)

You can see even more cool stuff about my book on

Preorder yours today from your favorite bookseller:

And please feel free to share news of my new book with

- friends

- relatives

- librarians

- and the harried and time-pressed everywhere!

#artb4bkfst

Learning to teach beginners. On the teaching philosophy of Sketchbook Skool

What is the role of feedback in learning? Especially when starting to do creative things, things that are ultimately pretty subjective? When there are no answers in the back of the book?

The biggest obstacle we need to overcome in learning to create is the belief that we can’t. That’s especially true when we learn as adults. We have spent our entire lives believing that we cannot do this thing, and now, unless we are convinced that we can, we will never get to a point of any sort of mastery.

The most difficult and crucial lesson for beginners is the importance of failure. You need to make a lot of mistakes. You need to feel good about those mistakes and recognize that they are opportunities to improve. You can’t allow those errors to overwhelm you and make you feel hopeless.

The biggest obstacle we need to overcome in learning to create is the belief that we can’t.

The reason that people struggle with failure is because they believe that their failures are reflections on who they are as human beings. “Only failures fail.” The fact, of course, is that everybody fails on the path to learning, that failing is the most important part of any education. Researchers have shown that people learn far more from watching others fail than they do from watching extremely accomplished people do things without making any mistakes. You can sit and watch Lebron James shoot baskets perfectly all season but that won’t prove very instructive in developing your own game.

It is much more difficult to look at our own failings as educational opportunities if our egos and self-image are wrapped up in success and failure. When we watch other people fail, we are able to separate failure from ourselves, to see the failure as ‘other’ and thus look at it objectively.That is why it is generally better to learn creative things in a group environment where we can see others struggling and failing. We can see where the mishap occurred or how the problem was not fully solved. The problem exists independently and facing it is an interesting challenge, rather than a demeaning disaster.

…failing is the most important part of any education

What is the value of a teacher’s comments to a new student?

In creative situations, where one’s ego and self-image are tied into the results of an exercise, any sort of perceived criticism can undermine that process. Because we are still so new at learning this new skill, it is difficult to accept that a mistake is not a reflection of who we are and an indication that we shouldn’t even bother tackling this lesson. That’s why we need as much encouragement as possible in the beginning phase of learning, a phase that can actually last for years. We need to develop self-confidence and faith in our own creative abilities and sometimes criticism of any kind can thwart that progress.

Students often ask for specific advice on how to improve their composition or how to use a certain medium more effectively, and some teachers are quick to provide lots of guidance, rules, and specific direction. I don’t know if that is especially effective. I find that most students are extremely vulnerable to the most benign sort of commentary — even if they asked for it. Simply telling somebody that they might want to consider a different composition, different medium, consider a slightly different approach, can be extremely undermining. There are so many open wounds as one is going through this creative rebirth that everyone involved must tread lightly. That includes the teacher, the student, and the relative looking over the shoulder.

I think it’s more effective to encourage students to experiment, to make more work, and to gradually developed their own answers to these questions. In fact, my experience is that almost all direct input from the teacher (inevitably an authority figure) is not particularly useful before the student has real confidence in their abilities. Instead the teacher should create an environment of trust, inspiration and fun. They should encourage the process, the experimentation and exploration, provide reassurance and safety, and do demonstrations in which they explain their own process, rather than making specific suggestions about the work the student has done. Turn the key, but don’t grab the wheel.

Turn the key, but don’t grab the wheel.

Many novice students believe that there are shortcuts available that once revealed will turn the student from an amateur into an expert. They want to know what brand of pen the teacher uses under the misimpression that the pen is the secret. The fact is that the student will do much better by discovering answers on their own, by studying the works of others, and by trial and error. There isn’t an accumulated body of knowledge that the student can acquire which will transform them. That knowledge only comes through years of work.

But that doesn’t mean the student can’t be delighted with their accomplishments almost immediately. Especially in the beginning of a creative education, progress happens quite quickly, simply by feeling empowered and free to actually make things. Sometimes that simple realization can wipe out years of anxiety around creative issues. And with that freedom comes an opportunity to continue working and develop one’s own style and techniques.

But that doesn’t mean the student can’t be delighted with their accomplishments almost immediately.

Personally I find that students with the most technical skills alone rarely make art that I find very interesting. Instead I’m far more excited by people who make mistakes and discover new and interesting ways to overcome them.

Learning the tried-and-true ways of making art is not necessarily the way to make great art. It is simply the way to rehash the lessons we’ve already learned, to make more art that is ready familiar. Instead you want to create new and exciting directions, to take risks, to see the world afresh, to find answers to new questions. Learning to draw is not like cooking Boeuf Bourguignon, a set of steps one can follow from raw ingredients to final delicious product. Instead it is a voyage, an excursion into the wilderness, an adventure that is mainly rewarding for its own sake, not for its results.

The teacher doesn’t have the answers. Only the student does.